The Gurkha's Daughter (12 page)

Read The Gurkha's Daughter Online

Authors: Prajwal Parajuly

Tags: #FICTION / Short Stories (single author)

And she didn't even call me to let me know she was in town, thought Rajiv. The fool didn't even know she just blabbered something she shouldn't have said.

“She was in a school group, and no one was allowed to contact relatives,” her mother instantly said.

It was a feeble lie.

“Shouldn't we at least call them first?” Sona asked.

She did, and was told the guest house had one last room left.

“Some Spanish girls canceled at the last minute because one of them was too sick to leave Delhi today,” she said with a laugh.

“Let's go, then,” Niveeta said.

“Will you be back for dinner?”

Rajiv had shopped for

paneer

and

kinema

earlier in the day and had even asked Sandeep to come home early to help with the cooking.

“We need to go put on

tika

at

mama

's,” Sona said. “We might just eat there. That's where everyone is.”

With great effort, he dragged their suitcases through the terrace, carried them down the stairs, wheeled them up the road and lugged them up the staircase at Andy's. No one helped him. When they checked in, no one bothered thanking him for getting a hundred-rupee discount, offered to those the owner at Andy's knew.

His aunt booked just one room, nullifying Niveeta's claim that she couldn't sleep unless she was alone. Niveeta sat down on one of the beds in their room, exclaiming with delight at the quaintness of the guest house. Rajiv shot her a look. She saw him look at her and subconsciously ran her hand over her side and back to see if her underwear band showed. She pulled her

T-shirt down a bit, pulled up her pants slightly and brought her hand to her hair.

Rajiv told his aunt he was leaving. She handed him a 500-rupee note for

Dashain

, but Rajiv wouldn't accept it despite how unyielding she was.

His grandmother was slowly negotiating the stairs to their place when he returned home. She was wondering where the guests were.

“They were stuck in Guwahati,” he said. “They might just head back home instead.”

“Silly peopleâyour mother's family,” she said.

“I think I'll go to bed early today,” said Rajiv.

“Also, Tikam called,” his grandmother said. “He won't be coming back. He says he'll stay home and learn farming.”

“I'll go to sleep. Have Sandeep cook you something.”

“He's not coming home, I am sure,” she said, leaving the room. “Just my luck to starve to death the day after

Tika

.”

He stared at Tikam's empty bed, put out the light, and lay down. He wondered what might transpire at

mama

's place tonight. Would they all be horrified at the idea of Niveeta's sleeping in the kitchen? He speculated about what the Scotts would have said. He thought of what his father would have done in a situation like this, what his mother would have had to say at the end of the day. Through the dark, he looked at where his parents' pictures hung, saw their faces in his mind's eye, and said a prayer over and over again. It was a Christian prayer he had been taught at St. Paul's.

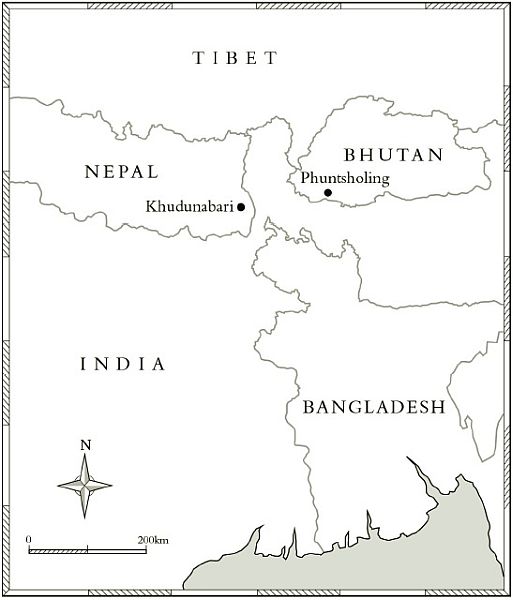

Anamika Chettri kicked off the tendrils that stubbornly clung to her feet as she stopped every fifty meters along the dirt trail to collect kindling. With the kerosene ration halved in the refugee camps and the coal briquettes aggravating her aging father's cough, the sticks available outside her camp in Khudunabari appeared to be her best option. Some of her neighbors said her father probably had TB and that Anamika should ask a camp doctor to have a look at himâa suggestion she paid no heed to, for she had too many things to worry about. There was no telling, anyway, what further problems a diagnosis would unravel.

Anamika rolled up her summer shawl, placed it on her head as a cushion and balanced the heavy bundle of wood on it before hiking down the trail with a tightrope walker's gait.

The college men were at the

singara

shop, their usual spot. Anamika's pace quickened. She steeled herself for what was to come by saying a silent prayer to God and mentally rehearsing suitable comebacks. Fear wouldn't paralyze her tongue the way it did many years ago. She had become adept at giving back the men what they deserved.

“

Wah

,” one of the four exclaimed. “Look at her walkâshe goes swish, swish, swish, swish.”

“Her hips swing like the clock's pendulum.” It was the long-haired rascal whom she had slapped in public last month.

“Is that why you keep staring at them?” Anamika snapped without looking back. “To tell the time? Because you can't read the clock, you illiterate fool?”

“Go back to your damn country.” Another voice, shriller than the rest, brought applause and hoots from the crew. “Go to Bhutan. No one wants you in Nepal.”

“Wait, I want her here. I want her all to myself.”

“Yes, shake your

condo

back to Bhutan. We don't need the likes of you to torture us with your looks here.”

“Stop bothering me, you mangy dogs.” A twig from her bundle fell. “Go back to your mothers and wives, but they are too busy dancing with the Maoists, aren't they?”

“

Lyaa

, Lutey, she called your wife a whore,” shouted the man she slapped. “It can't be my wife. I have no wife.”

“A whore calling a decent woman a whore.” Peals of laughter.

“She's thirty-five and has the mouth of a fifteen-year-old bitch. Who would think of a mother having such a filthy tongue? Her older daughter must have picked up all the good words by now. She looks just like her.”

“Yes, she looks just like me, and she's more of a man than you all will ever be.” The retorts today were better and faster than last week's.

“She looks so youngâhow can she have children?”

“Want me to show it to you?” Loud moans followed while Anamika tried to keep her face wooden.

“There are two of them.”

“No, three.”

“No, five.”

“She's a factory, a baby factory.” Loud laughter.

“Yes, except she likes changing the raw material to make babies with. Different fathers for different babies.”

“I learned that from your mother,

kukkur

,” she shouted.

She was inured to it all, hardly enraged. It was almost over. She had already turned the corner and was out of sight.

Anamika ran home, stopping only when she reached her hut and hurled the bundle in one corner. Her father was sleeping. At his feet, her daughters were writing Dzongkha letters on a notebook-sized blackboardâthe camp school had recently introduced Dzongkha studies in hopes that the children wouldn't find the repatriation process so difficult when Bhutan eventually allowed them in. Her neighbors, who lived in the adjoining hut and shared the outhouse with them, were slicing, dicing, pickling, and bottling raw mangoes behind the kitchen. The skies were overcast; she'd have to bring the clothes in before the rains came.

Anamika considered the refugee camp at Khudunabari her home. She wasn't the kind to stare into the open space and sigh longingly for Bhutan. Her theory was simple: if her country (she still referred to Bhutan as her country even after all these years) didn't want her, she didn't want it back. She had long ago learned to let goâof the eight acres of land her family owned close to Phuntsholing, of the cousins left behind who scraped through the citizenship test that, thanks to her husband, she had failed, and of the food, anointed with copious amounts of cheese and hot peppers, that she had never quite succeeded in replicating since she came to Nepal as one of the 106,000 ethnic-Nepalese refugees forced out of Bhutan.

Khudunabari wasn't all that different from Phuntsholing. The people looked alike, spoke Nepali with the expected variance in inflection, and followed the same religion and customs. The Bhutanese refugees at the camps often declared that they had done a better job of preserving the Nepalese culture than the Nepalese people themselves. Despite living in such familiar

surroundings, most refugees she spoke to were hoping for repatriation, unlike Anamika. She had had it with Bhutan. Her daughter's repetition of Dzongkha letters should have brought back memories, but it didn't. It was as though the girl were parroting English nursery rhymes, nothing more. Anamika felt no stirrings in her heart, as the camp folks often claimed, no sentiment for a country that was once her home.

“What did you learn at school today?” she asked neither of the girls in particular. Anamika had studied up to eighth grade in Phuntsholing.

“What would you understand, Aamaa?” Shambhavi, the ten-year-old, whispered. She could have shouted. Anamika's father could sleep through anythingâeven the agitation in Bhutan.

“I am not uneducated like our neighbors, Shambhavi, and you'll get a slap for talking back to me that way.”

“We talked about settling in some foreign country.”

“What do you mean?”

“Don't you know?” twelve-year-old Diki asked, shifting positions to avoid being hit by drops of water trickling through the roof.

Anamika asked her to place a bucket where the water had formed a small puddle on the mud floor. Some stray drops landed on the sleeping old man's toes and made the girls giggle.

“The America story? It's been going on since we first arrived here. At your age you believe everything they say, Diki.”

“But they say it's true this time,” Diki said. “America will take some of us.”

“Even if it is true, how do they choose who goes and who doesn't?” Anamika asked with a dismissive hand motion. “And what about those left behind?”

“They said in class that America would take those who are fit, not very old, and can speak English,” said Diki.

“Speak English?” Anamika said. “That means almost all of us cannot go.”

“But the teacher said we shouldn't talk about it too much,” Diki continued. “Some people do not like the idea of America taking us. They think that will make Bhutan happy, and they don't want Bhutan happy.”

“They've been talking about it for seventeen years, long before I came here,” said Anamika as she rubbed a handful of ash at the bottom of a burned pot and ran water over it. “One day it was London, and the next day it was Australia. I've stopped believing it.”

“Will we still get rations in America, Aamaa?” Shambhavi asked.

“Probably.”

“And will Baajey join us if we get to go? He is not young, not fit, and barely knows an English word.”

“If I knew all the answers, wouldn't I be God? Now go back to your studies. You take every opportunity to waste your time.”

Anamika had wasted a dozen years of her life at the camp. Back in Bhutan, she had at least been working, contributing to her family. Even after her marriage, she regularly deposited small amounts of money into her father's new Bank of Bhutan account. Her husband probably didn't notice because he was too busy enticing every Nepali-speaking Bhutanese within reach to join the revolution. For her husband, the passion for the cause of the ethnic Nepalese in Bhutan came belatedlyâyears after the Bhutanese government had silenced the first murmurs of dissent. He had changed in a short time, not in his behavior toward her, for he was still affectionate, but in the way he interacted with people around him. He was constantly organizing, had little by little cut off the few non-Nepali-speaking Bhutanese acquaintances from his life and stopped working altogether.

Their dream of starting their own business in partnership with an Indian Marwari from Jaigaon was just taking shapeâthe hardware store would technically be theirs, for the Marwari couldn't acquire a license as a foreigner in Bhutan. He'd run it, and they'd learn as much as they could while sharing the profits before finally going at another venture alone. Anamika would resign from her government job in a few weeks while her husband carried on working until the enterprise generated a profit. It had all been perfectly mapped out.

But the business planning halted, and her husband stopped going to his job as a typist in the court at Phuntsholing. If the new people's hero did show up at work, it was at odd hours, brandishing an antimonarchy pamphlet and dressed in

daura suruwal

, the Nepali costume for men, despite the Bhutanese government's having just mandated that only traditional Bhutanese attire be worn at offices. From a belt around his waist dangled a sheathed

khukuri

, the curved Nepalese knife, with his hand often resting on the wooden handle. Half a dozen men, most of whom dressed like him, always accompanied her husband.

Anamika returned home from work one day to discuss whether it was wise to quit her job the next week, as had been planned, when issues like job security and money were still important to her husband. Things weren't the same as before, what with her husband's not working, and she wanted to be sure before she took so dramatic a step.

“Why quit?” he absentmindedly said without looking up from the back of a calendar, on which he was scribbling notes. “It's our government also. Or have you begun believing them when they say we don't belong here? We may be ethnic Nepali, but we are Bhutanese, too.”

“What about starting the store? We need time. I need to learn.”

“Tell me if that's good.” He threw a carefully coined slogan at her. “We are humans, not animals. We should be allowed to speak our language, not bark yours.”

He said it with a singsong cadence, repeated it and found something amiss.

“No, no, that didn't come out right. Let's try this: âOne people, one country' doesn't work when we are made to feel like the others.”

“They have finally stopped throwing people out by the truckloads near the borders.” Anamika wanted to tear his notebook. “They may start again because of your demonstrations. Should we risk being let out?”

“The kingâthe king has to go. We are Bhutanese, too, so what if we are a little different from the majority of you?”

“The store, what about the store?” Anamika asked, aware she had slipped into the same lilt as he did with his slogans.

“The king, the king, out with the king,” he sang. “A democracy is what we need.”

Pleased, he wrote it down.

“Wait, this one is slightly better. The king, the king, out with the king. A democracy is the need of the hour.”

“Do you want something to eat?” She was exhausted.

“Ethnicity, ethnicity,” he shouted. “We're being kicked out for no other reason than our ethnicity.”

“Should I serve you food?”

She hadn't cooked anything. Neither had he.

“Do away with 1958. Some of us can show you the documents while others, we cannot.” He was referring to the 1958 citizenship documents the government required all Nepali-speaking people residing in the country to procure as proof of their citizenship. “We have papers from 1957, we have papers from 1959. But to you, merciless king, none but 1958 will do. Thoo, thoo, thoo,” he venomously spat out three times.

Anamika soon found out that Diki's talk about resettlement hadn't been entirely incorrect. The camp was abuzz with excitement about the recent developments. Everyone knew scraps of information, but no one had the details.

Yes, America was settling sixty thousand of them in her states. No force was used. Yes, everyone knew someone who knew someone an American had already interviewed at the International Organization for Migration office in Damak. Someone said every family would have a separate bathroomâsometimes, even two bathroomsâand no one would go hungry. America would also give them jobs and teach them English. It would be difficult to teach the old ones, so America didn't like them so much. Maybe America would use the young ones to fight the Muslims, a neighbor pointed out. Thankfully, America disliked Muslims but liked Hindus and Buddhists the best.

The interviews would take place in the same red air-conditioned building where the blood tests would be done. Yes, the women wore pants, and only pants, in America, and the men weren't allowed to lay hands on women. They could still beat up the wives secretly, but the wives could always inform the police. No, no, no, another know-it-all said, don't try your “sir/madam”

chamchagiri

; the Americans saw right through you when you tried to flatter them, because they went to school to gauge that. Yes, England might take some. And maybe Australia and Norway, too.