The Gurkha's Daughter (15 page)

Read The Gurkha's Daughter Online

Authors: Prajwal Parajuly

Tags: #FICTION / Short Stories (single author)

The day after Gita and I combined our miniature kitchen sets, we boasted to the other girls at Rhododendron International Boarding School that we owned a bigger

bhara-kuti

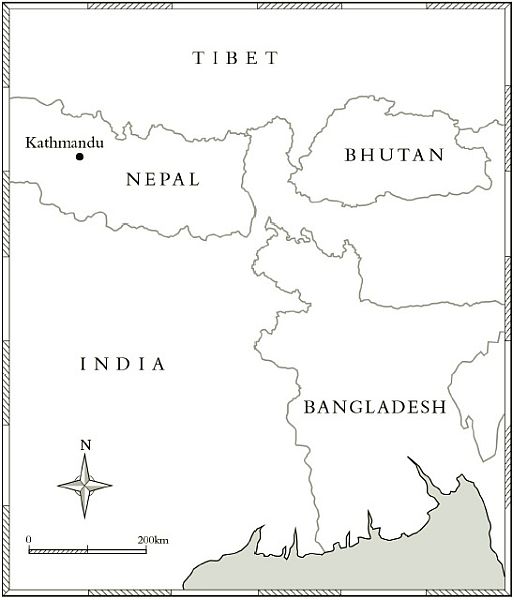

collection than any other nine-year-old in Kathmandu. We had steel utensils, plastic ones, a glass set and gold-plated ones, and these did not include the new set Gurung Bada and Appa had recently sent us from Hong Kong. In addition, Aamaa had, in a charitable mood, given us a few platesâreal-life platesâfrom her kitchen. The glass set we used when we had special pretend guests.

That day, our special guests would be our Gurkha fathers. We'd play our respective fathers and ourselves. Gita had stolen two fake mustachios from Drama Sir's desk in the staff room.

We donned our mustachios, and Gita even wore a black hat. Gurung Bada never wore a hat, but Gita took a little wardrobe liberty. Her Phantom cigarette sweet that dangled between her lips was again out of characterâfor neither of our fathers smokedâbut I didn't mind because she gave me one, too, which I tucked above my ear.

“Give me some beer, Budi.” Gita looked back. “And Gita, turn the

jaabo

tape recorder off. Your Appa and Bada are talking.”

“Okay, Appa,” Gita said in a meek voice, and took off her mustache.

“We are nothing but killing machines to them,” Gita spat out, her mustache back on. “They still treat us like dogs.”

“No, Numberee, no, don't be angry,” I said, not knowing what to add.

“All these years in service, but will they take care of us after that?” Gita said, angry. “No. We will be discarded like socks and shoes. The pension will be worth nothing. How is it that all the other regiments in the British Army get a proper pension? It's only us, brave Gurkhas, who get a fifth of what the others get. Brave indeed! Foolish is what it is.”

“Let's count our blessings, Numberee,” I countered, stopping my mustache from falling by supporting it with my thumb. “We'd otherwise be in the police, making nothing. What is there to do in this country? We are lucky we got out on time.”

“And that McFerron

chutiya

,” Gita slurred, taking swigs of water from her miniature glass cup and almost breaking it when she placed it on the ground with force. “He has asked me to bring my drinking down, like it's his father's alcohol I am consuming. Stupid Tommy Atkins that he isâhe thinks we are unequal. I haven't created a scene, have I? I haven't picked fights with anyone. I am a peaceful drinker. But the white bastard doesn't think so. I am tired of it.”

“Think of it, Numberee,” I said, conscious that my part was small and that I wasn't doing a very good job of it. “Our daughters are in a good English-language school. Our wives live well.”

“I think I will be the first Gurkha court-martialed because McFerron doesn't like me drinking.” Gita was now biting her cigarette sweet. “Bloody English.”

“He says he's Irish.”

“English, Irish, Scottishâwho cares?” She drank some more of the imaginary beer. “They are all the same to me. They all get regular pensionsâfive times more than we do. It's only we who are inferior to themâwe the brave Gurkhas.”

“Aamaa, I am hungry,” I said, taking my mustache off.

“Yes, Budi, I am hungry, too,” Gita said, her mustache still on. “Feed us Gurkhas, feed us brave people and our families, for with the pension we receive, we may be starving a few years from now.”

“

Aayo bir Gurkhali

,” Gita sang, in an unmistakable imitation of Gurung Bada's voice. It was a song both Gita and I knewâour fathers had taught us. Sometimes, our mothers sang it to us as a lullaby. I joined in as Gita sang one line in her father's voice (with the mustache on) and another in hers (with the mustache off). I tried doing the same, but both my voices sounded similar.

Gita had only the bottom pink portion of her cigarette left.

“Here,” I said, breaking mine into half. “You can eat some of mine.”

She bit the half into another half.

“Delicious,” she said.

“I know,” I said, and then back in character again, with the mustache on, I added, “Let's eat all we can here because there is no food like home food. Numberee, this is after so long that both your family and my family are together under the same roof.”

“Yes, I know.” Gita said, bored now.

I'd need to think of a new character to keep her interested.

“Call the pointy-nosed astrologer,” I said. “Call him so we can all see the white hairs covering his ears.”

Gita procured two cotton wool balls, spat on them and glued them to her ears. I'd have to try and replay everything the pointy-nosed astrologer had said the day before. A few things, though, Appa and Aamaa warned me, I couldn't even share with Gita, especially with Gita.

The pointy-nosed astrologer had looked at me, back at my birth chart and then let his eyes wander around the rooftop. Exposed

iron rods jutted out vertically from the edges of the terrace in desperation, for it would be a long time before we expanded our one-story house into a multistoried one, Appa's dream before he retired from the British Army.

“Here,

naani

, eat this guava and go to play,” the astrologer had said to me.

I took the guava, small, green, and hard, and sat still. His order held no real authority, no threat. It was weak, like his voice, and like, as I'd soon discover, my birth chart.

“Not good,” he told Appa. “There's a

dosha

on her chartâa kind of

kala sharpa dosha.

She will bring you bad luck for another few years.”

Appa frowned, the way he did when I asked him why he took my spot next to Aamaa in bed when he was in Kathmandu. Ever since he came back from Hong Kong on vacation, a slew of astrologers had confirmed what my birth chart clearly stated: that I was unlucky for Appa, that the house would not be completed until I was past fifteen and that I was accident prone and

Manglik

, which meant I'd have trouble finding a man to get married to.

“Bad luck?” Appa said. “What bad luck? I acquired this piece of land after she was born, began building this house after she was born. Those bastard British captains at the regiment began treating me like a human being after she was born.”

“All that might be true, but the next few years will be tough.” The priest scowled, his forehead wrinkling into six uniform lines. “Let's seeâshe's nine now. Even after the

dosha

ends, things will continue this way for five or six years. See, I could be like other priests and ask you to do an elaborate

puja,

but I won't.”

Aamaa played with the loose end of her purple sari, the one she wore on special occasions at home. When outside, she wore her prettier, shinier silk saris, but inside, she often dressed in

this purple one with a purple blouse, the purple-on-purple hidingâor at least taking attention fromâthe slight tear on her blouse shoulder.

“What is the solution then, Punditjee?” she asked. “I have gone to Manakamana, to Pashupatinath. If you can think of more temples, I will go to them, too.”

I bit my guava. It didn't have much of a taste, so I almost threw it away. But I stopped myself because of the religious atmosphere at home. A priest, grains of uncooked rice sprinkled on the birth chart before the priest opened it, and the donning of special clothes convinced me that the fruit, an offering to God first, might be sacred. I balled it into my fist and concentrated on the white hairs sprouting from the pointy-nosed astrologer's ears.

“I don't believe in a

puja

to appease the gods,” the astrologer said dismissively. “What we can try to do is shift her bad luck to someone elseâpreferably a girl her age. Can you think of someone we can bind her in a

miteri

ceremony with? That could change things a littleânot a lot, mind you, for there isn't much we can do when one has a

cheena

this bad, and I am not one of those astrologers who believe that the course of a person's fortune can be changed with rituals, but this we can try. I've done it a few times in the past, and it has mostly worked.”

Appa, still frowning, asked Aamaa for the red envelope they had earlier readied for the priest, stuffed another fifty-rupee note, bright and crisp, into it and told the pointy-nosed astrologer he'd be in touch shortly.

“I want to settle this problem before I head back to Hong Kong,” he said. “I haven't been in any danger since the Gulf War, but they might have some useless war for me to fight again. They are the British after all. And it will be a long time before I am in Kathmandu. Thank you, Punditjee. We cooked quite a feast, but you perhaps don't eat anything cooked by us Magars.”

“I am a new-age pundit.” The astrologer smiled proudly. “I don't make distinctions based on caste like my fellow priests. As long as you didn't prepare meat, I'll eat everything.”

Appa and Aamaa both broke into such wide smiles that I could see Appa's missing molar and Aamaa's gold tooth.

“I'll hurry downstairs and get the plates ready, then,” Aamaa said. “We don't cook meat when we invite a priest to the house. Never.”

“Yes, and show me the house in the meantimeâwhat little of it is complete anyway,” the astrologer asked. “Come, you little one, you unlucky one, let's fill our stomachs before we think up ways to change your life.”

I got up, the guava still in my fist, and waited for Appa and the pointy-nosed astrologer to head down the stairs. Using all my strength, I bowled the guava, the same way I saw cricketers on TV do, out on the street, which was at the same level as the terrace, and almost hit a cyclist. He raised his arm menacingly at me. I waved back at him and laughed. The story would definitely make Gita giggle. She'd probably even suggest that we collect all the fallen guavas off the grounds near my half-constructed house and aim them at the steady traffic of pedestrians that went by the terrace. It could be another one of our secrets.

If the pointy-nosed astrologer could predict the future, I wondered if he'd know of my secretsâthe smaller one with Aamaa, which Gita and her mother also knew, and the bigger one, the more important one, with Gita. Asking him would just arouse his suspicions. I'd have to ask Gita how to bring it up with him.

Gita was fair and clean and even brushed her teeth at night. She wore a maxi nightdress to bed and could run faster than any of us. She was better at

pittu

than the boys and so often

completely toppled the tower of tiny stone slabs with her plastic ball that the boys always wanted her on their team. Gita was Gurung Bada's daughter. Gurung Bada was Appa's close friend from the regiment. Gurung Badi and my mother claimed they were related, but Appa, on more than one occasion, said that wasn't true.

“These Darjeeling women jump to make everyone their relativesânever mind that they are of different castes and have not a drop of common blood,” he said a few days ago. “Tomorrow your Aamaa will look for that common blood in me. How can she even consider sharing the same blood as that child devil called Gita?”

I didn't say a word in defense of my best friend's monstrosity and instead conjured a memory of what she and I had indulged in the day beforeâSecret Number One, the bigger secret. Would Appa be angry if he found out? Aamaa would be petrified. She had warned me countless times that eating what had touched someone else's mouth would cause boils all over my face. It was even worse than double dipping a samosa. I'd get both my ears pulled. And she'd complain to Gita's mother, who could be a terror. Gurung Badi sometimes even beat Gita with her special stick, a

gauri bet

, the marks of which stubbornly stayed for days. But Aamaa would never find out. Gurung Badi would never find out. It was our big secret, and no one would find out.

It happened the first day of school after the winter break. Gita and I returned to my house from RIBS, our hated school, together. Once we turned eight, because we didn't have to cross a street to get to the institution from my place, our mothers allowed us to walk to and from school by ourselves. Aamaa wasn't in the house, and Appa was never home at this time when he was in the country, so we took the keys from the storekeeper down the street to find a steel bowl of cold Ra-ra waiting for me on the dining table.

“Firstselectiongreen!” Gita shouted once she saw the bowl, grazing the green on the door.

Had she not touched it, I'd have shown her my palmâwhere I squiggled in green every day for eventualities when the color would be out of reachâand yelled “Firstselectiongreen,” winning the opportunity to select between two portions into which I'd now divide the bowl of Ra-ra. Gita might not have employed the trick of wearing the color every day or scribbling with a green sketch pen on her palm, but she still regularly beat me to laying claim on the first selection.