The Hiding Place (2 page)

At the close of the service, I stayed behind to talk with her. Cornelia ten Boom, it was apparent, had found in a concentration camp, as the prophet Isaiah foretold, a “hiding place from the wind, and a covert from the tempest . . . the shadow of a great rock in a weary land” (Isaiah 32:2).

With my husband, John, I returned to Europe to get to know this amazing woman. Together we visited the crooked little Dutch house, one room wide, where until her fifties she lived the uneventful life of a spinster watchmakerâlittle dreaming as she cared for her older sister and their elderly father that a world of high adventure and deadly danger lay just around the corner. We went to the garden in southern Holland where young Corrie gave her heart away forever. To the big brick house in Haarlem where Pickwick served real coffee in the middle of the war.

And all the while we had the extraordinary feeling that we were looking not into the past but into the future. As though these people and places were speaking to us not about things that had already happened but about the experiences that lay ahead of us. Already we found ourselves putting into practice what we learned from her about the following:

⢠handling separation

⢠getting along with less

⢠security in the midst of insecurity

⢠forgiveness

⢠how God can use weakness

⢠dealing with difficult people

⢠facing death

⢠loving your enemies

⢠what to do when evil wins

W

E COMMENTED

to Corrie about the practicalness of the things she recalled, how her memories seemed to throw a spotlight on problems and decisions we faced here and now. “But,” she said, “this is what the past is for! Every experience God gives us, every person He puts in our lives is the perfect preparation for a future that only He can see.”

Every experience, every person. . . . Father, who did the finest watch repairs in Holland and then forgot to send the bill. Mama, whose body became a prison but whose spirit soared free. Betsie, who could make a party out of three potatoes and some twice-used tea leaves. As we looked into the twinkling blue eyes of this undefeatable woman, we wished that these people had been part of our own lives.

And then, of course, we realized that they could be. . . .

Elizabeth Sherrill

Chappaqua, New York

September 2005

A

nyone who thinks Christianity is boring has not yet been introduced

to my friend Corrie ten Boom!

One of the qualities I admired best about this remarkable lady was her zest for adventure. Although she was many years my senior, she traveled tirelessly with me behind the Iron Curtain, meeting with clandestine Christian cell groups in the days when this meant risking prison or deportation.

“They're putting their lives on the line for what they believe,” she would say. “Why shouldn't I?”

If Corrie were alive today, I have no doubt she would insist on going with me to the current hot spots of persecution. And how she would delight in sharing her radical faith with bold believers like the Christian Motorcycle Association, that wonderful group of men and women who often drive their bikes into poor countries, then give them away to pastors who have no other way to get around.

If you have never met Corrie ten Boom, the best way to enter into a lifetime friendship with her and her Lord is through the pages of this book. As

The Hiding Place

celebrates its 35th anniversary, a new generation is responding to her ringing challenge: “Come with me and step into the greatest adventure you will ever know.”

Brother Andrew

founder, Open Doors

author,

God's Smuggler

1

The One Hundredth Birthday Party

I

jumped out of bed that morning with one question in my mindâsun or fog? Usually it was fog in January in Holland, dank, chill, and gray. But occasionallyâon a rare and magic dayâa white winter sun broke through. I leaned as far as I could from the single window in my bedroom; it was always hard to see the sky from the Beje. Blank brick walls looked back at me, the backs of other ancient buildings in this crowded center of old Haarlem. But up there where my neck craned to see, above the crazy roofs and crooked chimneys, was a square of pale pearl sky. It was going to be a sunny day for the party!

I attempted a little waltz as I took my new dress from the tipsy old wardrobe against the wall. Father's bedroom was directly under mine but at seventy-seven he slept soundly. That was one advantage to growing old, I thought, as I worked my arms into the sleeves and surveyed the effect in the mirror on the wardrobe door. Although some Dutch women in 1937 were wearing their skirts knee-length, mine was still a cautious three inches above my shoes.

You're not growing younger yourself

, I reminded my reflection. Maybe it was the new dress that made me look more critically at myself than usual: 45 years old, unmarried, waistline long since vanished.

My sister Betsie, though seven years older than I, still had that slender grace that made people turn and look after her in the street. Heaven knows it wasn't her clothes; our little watch shop had never made much money. But when Betsie put on a dress something wonderful happened to it.

On meâuntil Betsie caught up with themâhems sagged, stockings tore, and collars twisted. But today, I thought, standing back from the mirror as far as I could in the small room, the effect of dark maroon was very smart.

Far below me down on the street, the doorbell rang. Callers? Before 7:00 in the morning? I opened my bedroom door and plunged down the steep twisting stairway. These stairs were an afterthought in this curious old house. Actually it was two houses. The one in front was a typical tiny old-Haarlem structure, three stories high, two rooms deep, and only one room wide. At some unknown point in its long history, its rear wall had been knocked through to join it with the even thinner, steeper house in back of itâwhich had only three rooms, one on top of the otherâand this narrow corkscrew staircase squeezed between the two.

Quick as I was, Betsie was at the door ahead of me. An enormous spray of flowers filled the doorway. As Betsie took them, a small delivery boy appeared. “Nice day for the party, Miss,” he said, trying to peer past the flowers as though coffee and cake might already be set out. He would be coming to the party later, as indeed, it seemed, would all of Haarlem.

Betsie and I searched the bouquet for the card. “Pickwick!” we shouted together.

Pickwick was an enormously wealthy customer who not only bought the very finest watches but often came upstairs to the family part of the house above the shop. His real name was Herman Sluring; Pickwick was the name Betsie and I used between ourselves because he looked so incredibly like the illustrator's drawing in our copy of Dickens. Herman Sluring was without doubt the ugliest man in Haarlem. Short, immensely fat, head bald as a Holland cheese, he was so wall-eyed that you were never quite sure whether he was looking at you or someone elseâand as kind and generous as he was fearsome to look at.

The flowers had come to the side door, the door the family used, opening onto a tiny alleyway, and Betsie and I carried them from the little hall into the shop. First was the workroom where watches and clocks were repaired. There was the high bench over which Father had bent for so many years, doing the delicate, painstaking work that was known as the finest in Holland. And there in the center of the room was my bench, and next to mine Hans the apprentice's, and against the wall old Christoffels'.

Beyond the workroom was the customers' part of the shop with its glass case full of watches. All the wall clocks were striking 7:00 as Betsie and I carried the flowers in and looked for the most artistic spot to put them. Ever since childhood I had loved to step into this room where a hundred ticking voices welcomed me. It was still dark inside because the shutters had not been drawn back from the windows on the street. I unlocked the street door and stepped out into the Barteljorisstraat. The other shops up and down the narrow street were shuttered and silent: the optician's next door, the dress shop, the baker's, Weil's Furriers across the street.

I folded back our shutters and stood for a minute admiring the window display that Betsie and I had at last agreed upon. This window was always a great source of debate between us, I wanting to display as much of our stock as could be squeezed onto the shelf, and Betsie maintaining that two or three beautiful watches, with perhaps a piece of silk or satin swirled beneath, was more elegant and more inviting. But this time the window satisfied us both: it held a collection of clocks and pocketwatches all at least a hundred years old, borrowed for the occasion from friends and antique dealers all over the city. For today was the shop's one hundredth birthday. It was on this day in January 1837 that Father's father had placed in this window a sign: ten boom. watches.

For the last ten minutes, with a heavenly disregard for the precisions of passing time, the church bells of Haarlem had been pealing out 7:00 and now half a block away in the town square, the great bell of St. Bavo's solemnly donged seven times. I lingered in the street to count them, though it was cold in the January dawn. Of course everyone in Haarlem had radios now, but I could remember when the life of the city had run on St. Bavo time, and only trainmen and others who needed to know the exact hour had come here to read the “astronomical clock.” Father would take the train to Amsterdam each week to bring back the time from the Naval Observatory and it was a source of pride to him that the astronomical clock was never more than two seconds off in the seven days. There it stood now, as I stepped back into the shop, still tall and gleaming on its concrete block, but shorn now of eminence.

The doorbell on the alley was ringing again; more flowers. So it went for an hour, large bouquets and small ones, elaborate set pieces and home-grown plants in clay pots. For although the party was for the shop, the affection of the city was for Father. “Haarlem's Grand Old Man” they called him and they were setting about to prove it. When the shop and the workroom would not hold another bouquet, Betsie and I started carrying them upstairs to the two rooms above the shop. Though it was twenty years since her death, these were still “Tante Jans's rooms.” Tante Jans was Mother's older sister and her presence lingered in the massive dark furniture she had left behind her. Betsie set down a pot of greenhouse-grown tulips and stepped back with a little cry of pleasure.

“Corrie, just look how much brighter!”

Poor Betsie. The Beje was so closed in by the houses around that the window plants she started each spring never grew tall enough to bloom.

At 7:45 Hans, the apprentice, arrived and at 8:00 Toos, our saleslady-bookkeeper. Toos was a sour-faced, scowling individual whose ill-temper had made it impossible for her to keep a job untilâten years agoâshe had come to work for Father. Father's gentle courtesy had disarmed and mellowed her and, though she would have died sooner than admit it, she loved him as fiercely as she disliked the rest of the world. We left Hans and Toos to answer the doorbell and went upstairs to get breakfast.

Only three places at the table

, I thought, as I set out the plates. The dining room was in the house at the rear, five steps higher than the shop but lower than Tante Jans's rooms. To me this room with its single window looking into the alley was the heart of the home. This table, with a blanket thrown over it, had made me a tent or a pirate's cove when I was small. I'd done my homework here as a schoolchild. Here Mama read aloud from Dickens on winter evenings while the coal whistled in the brick hearth and cast a red glow over the tile proclaiming, “Jesus is Victor.”

We used only a corner of the table now, Father, Betsie, and I, but to me the rest of the family was always there. There was Mama's chair, and the three aunts' places over there (not only Tante Jans but Mama's other two sisters had also lived with us). Next to me had sat my other sister, Nollie, and Willem, the only boy in the family, there beside Father.

Nollie and Willem had had homes of their own many years now, and Mama and the aunts were dead, but still I seemed to see them here. Of course their chairs hadn't stayed empty long. Father could never bear a house without children, and whenever he heard of a child in need of a home a new face would appear at the table. Somehow, out of his watch shop that never made money, he fed and dressed and cared for eleven more children after his own four were grown. But now these, too, had grown up and married or gone off to work, and so I laid three plates on the table.

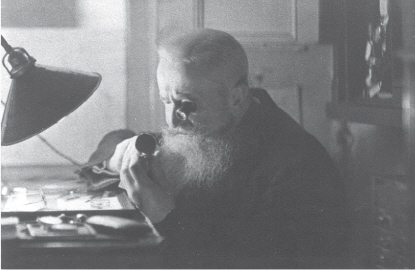

Casper was an expert watchmaker for more than sixty years.

Betsie brought the coffee in from the tiny kitchen, which was little more than a closet off the dining room, and took bread from the drawer in the sideboard. She was setting them on the table when we heard Father's step coming down the staircase. He went a little slowly now on the winding stairs; but still as punctual as one of his own watches, he entered the dining room, as he had every morning since I could remember, at 8:10.