The Hiding Place (5 page)

“Shhh!” Betsie and Nollie were waiting for me outside the dining room door. “For heaven's sake, Corrie, don't do anything to get Tante Jans started wrong,” Betsie said. “I'm sure,” she added doubtfully, “that Father and Mama and Tante Anna will like Nollie's hat.”

“Tante Bep won't,” I said.

“She never likes anything,” Nollie said, “so she doesn't count.”

Tante Bep, with her perpetual, disapproving scowl, was the oldest of the aunts and the one we children liked least. For thirty years she had worked as a governess in wealthy families and she continually compared our behavior with that of the young ladies and gentlemen she was used to.

Betsie pointed to the Frisian clock on the stair wall, and with a finger on her lips silently opened the dining room door. It was 8:12: breakfast had already begun.

“Two minutes late!” cried Willem triumphantly.

“The Waller children were never late,” said Tante Bep.

“But they're here!” said Father. “And the room is brighter!”

The three of us hardly heard: Tante Jans's chair was empty.

“Is Tante Jans staying in bed today?” asked Betsie hopefully as we hung our hats on their pegs.

“She's making herself a tonic in the kitchen,” said Mama. She leaned forward to pour our coffee and lowered her voice. “We must all be specially considerate of dear Jans today. This is the day her husband's sister died some years agoâor was it his cousin?”

“I thought it was his aunt,” said Tante Anna.

“It was a cousin and it was a mercy,” said Tante Bep.

“At any rate,” Mama hurried on, “you know how these anniversaries upset dear Jans, so we must all try to make it up to her.”

Betsie cut three slices from the round loaf of bread while I looked around the table trying to decide which adult would be most enthusiastic about my decision to stay at home. Father, I knew, put an almost religious importance on education. He himself had had to stop school early to go to work in the watch shop, and though he had gone on to teach himself history, theology, and literature in five languages, he always regretted the missed schooling. He would want me to goâand whatever Father wanted, Mama wanted too.

Tante Anna then? She'd often told me she couldn't manage without me to run errands up and down the steep stairs. Since Mama was not strong, Tante Anna did most of the heavy housework for our family of nine. She was the youngest of the four sisters, with a spirit as generous as Mama's own. There was a myth in our family, firmly believed in by all, that Tante Anna received wages for this workâand indeed every Saturday, Father faithfully paid her one guilder. But by Wednesday when the greengrocer came he often had to ask for it back, and she always had it, unspent and waiting. Yes, she would be my ally in this business.

“Tante Anna,” I began, “I've been thinking about you working so hard all day when I'm in school andâ”

A deep dramatic intake of breath made us all look up. Tante Jans was standing in the kitchen doorway, a tumbler of thick brown liquid in her hand. When she had filled her chest with air, she closed her eyes, lifted the glass to her lips, and drained it down. Then with a sigh she let out the breath, set the glass on the sideboard, and sat down.

“And yet,” she said, as though we had been discussing the subject, “what do doctors know? Dr. Blinker prescribed this tonicâbut what can medicine really do? What good does anything do when one's Day arrives?”

I glanced round the table; no one was smiling. Tante Jans's preoccupation with death might have been funny, but it wasn't. Young as I was, I knew that fear is never funny.

“And yet, Jans,” Father remonstrated gently, “medicine has prolonged many a life.”

“It didn't help Zusje! And she had the finest doctors in Rotterdam. It was this very day when she was takenâand she was no older than I am now, and got up and dressed for breakfast that day, just as I have.”

She was launching into a minute-by-minute account of Zusje's final day when her eyes lit on the peg from which dangled Nollie's new hat.

“A fur muff?” she demanded, each word bristling with suspicion.

“At this time of year!”

“It isn't a muff, Tante Jans,” said Nollie in a small voice.

“And is it possible to learn what it is?”

“It's a hat, Tante Jans,” Betsie answered for her, “a surprise from Mrs. van Dyver. Wasn't it nice ofâ”

“Oh no. Nollie's hat has a brim, as a well-brought-up girl's should. I know. I boughtâand paidâfor it myself.”

There were flames in Tante Jans's eyes, tears in Nollie's when Mama came to the rescue. “I'm not at

all

sure this cheese is fresh!” She sniffed at the big pot of yellow cheese in the center of the table and pushed it across to Father. “What do you think, Casper?”

Father, who was incapable of practicing deceit or even recognizing it, took a long and earnest sniff. “I'm sure it's perfectly fine, my dear! Fresh as the day it came. Mr. Steerwijk's cheese is alwaysâ”

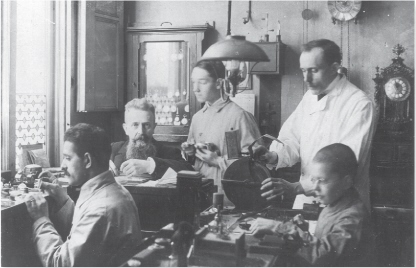

A busy watch-shop workroom in 1913.

Catching Mama's look he stared from her to Jans in confusion. “Ohâerâah, Jansâah, what do you think?”

Tante Jans seized the pot and glared into it with righteous zeal. If there was one subject which engaged her energies even more completely than modern clothing it was spoiled food. At last, almost reluctantly it seemed to me, she approved the cheese, but the hat was forgotten. She had plunged into the sad story of an acquaintance “my very age” who had died after eating a questionable fish, when the shop people arrived and Father took down the heavy Bible from its shelf.

There were only two employees in the watch shop in 1898, the clock man and Father's young apprentice-errand boy. When Mama had poured their coffee, Father put on his rimless spectacles and began to read: “Thy word is a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path. . . . Thou art my hiding place and my shield: I hope in thy word. . . .”

What kind of hiding place?

I wondered idly as I watched Father's brown beard rise and fall with the words. What was there to hide from?

It was a long, long psalm; beside me Nollie began to squirm. When at last Father closed the big volume, she, Willem, and Betsie were on their feet in an instant and snatching up their hats. Next minute they had raced down the last five stairs and out the alley door.

More slowly the two shopworkers got up and followed them down the stairs to the shop's rear entrance. Only then did the five adults notice me still seated at the table.

“Corrie!” cried Mama. “Have you forgotten you're a big girl now?

Today you go to school too! Hurry, or you must cross the street alone!”

“I'm not going.”

There was a short, startled silence, broken by everybody at once.

“When I was a girlâ” Tante Jans began.

“Mrs. Waller's childrenâ” from Tante Bep.

But Father's deep voice drowned them out. “Of course she's not going alone! Nollie was excited today and forgot to wait, that's all. Corrie is going with me.”

And with that he took my hat from its peg, wrapped my hand in his, and led me from the room. My hand in Father's! That meant the windmill on the Spaarne, or swans on the canal. But this time he was taking me where I didn't want to go! There was a railing along the bottom five steps: I grabbed it with my free hand and held on. Skilled watchmaker's fingers closed over mine and gently unwound them. Howling and struggling, I was led away from the world I knew into a bigger, stranger, harder one. . . .

M

ONDAYS

, F

ATHER TOOK

the train to Amsterdam to get the time from the Naval Observatory. Now that I had started school it was only in the summer that I could go with him. I would race downstairs to the shop, scrubbed, buttoned, and pronounced passable by Betsie. Father would be giving last-minute instructions to the apprentice. “Mrs. Staal will be in this morning to pick up her watch. This clock goes to the Bakker's in Bloemendaal.”

And then we would be off to the station, hand in hand, I lengthening my strides and he shortening his to keep in step. The train trip to Amsterdam took only half an hour, but it was a wonderful ride. First the close-wedged buildings of old Haarlem gave way to separate houses with little plots of land around them. The spaces between houses grew wider. And then we were in the country, the flat Dutch farmland stretching to the horizon, ruler-straight canals sweeping past the window. At last, Amsterdam, even bigger than Haarlem, with its bewilderment of strange streets and canals.

Father always arrived a couple of hours before the time signal in order to visit the wholesalers who supplied him with watches and parts. Many of these were Jews, and these were the visits we both liked best. After the briefest possible discussion of business, Father would draw a small Bible from his traveling case; the wholesaler, whose beard would be even longer and fuller than Father's, would snatch a book or a scroll out of a drawer, clap a prayer cap onto his head; and the two of them would be off, arguing, comparing, interrupting, contradictingâreveling in each other's company.

And then, just when I had decided that this time I had really been forgotten, the wholesaler would look up, catch sight of me as though for the first time, and strike his forehead with the heel of his hand.

“A guest! A guest in my gates and I have offered her no refreshment!” And springing up he would rummage under shelves and into cupboards and before long I would be holding on my lap a plate of the most delicious treats in the worldâhoney cakes and date cakes and a kind of confection of nuts, fruits, and sugar. Desserts were rare in the Beje, sticky delights like these unknown.

By five minutes before noon we were always back at the train station, standing at a point on the platform from which we had a good view of the tower of the Naval Observatory. On the top of the tower where it could be seen by all the ships in the harbor was a tall shaft with two movable arms. At the stroke of 12:00 noon each day the arms dropped. Father would stand at his vantage point on the platform almost on tiptoe with the joy of precision, holding his pocket watch and a pad and pencil. There! Four seconds fast. Within an hour the “astronomical clock” in the shop in Haarlem would be accurate to the second.

On the train trip home we no longer gazed out the window. Instead we talkedâabout different things as the years passed. Betsie's graduation from secondary school in spite of the months missed with illness. Whether Willem, when he graduated, would get the scholarship that would let him go on to the university. Betsie starting work as Father's bookkeeper in the shop.

Oftentimes I would use the trip home to bring up things that were troubling me, since anything I asked at home was promptly answered by the aunts. OnceâI must have been ten or elevenâI asked Father about a poem we had read at school the winter before. One line had described “a young man whose face was not shadowed by sexsin.” I had been far too shy to ask the teacher what it meant, and Mama had blushed scarlet when I consulted her. In those days just after the turn of the century, sex was never discussed, even at home.

So the line had stuck in my head. “Sex,” I was pretty sure, meant whether you were a boy or a girl, and “sin” made Tante Jans very angry, but what the two together meant I could not imagine. And so, seated next to Father in the train compartment, I suddenly asked, “Father, what is sexsin?”

He turned to look at me, as he always did when answering a question, but to my surprise he said nothing. At last he stood up, lifted his traveling case from the rack over our heads, and set it on the floor.

“Will you carry it off the train, Corrie?” he said.

I stood up and tugged at it. It was crammed with the watches and spare parts he had purchased that morning.

“It's too heavy,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “And it would be a pretty poor father who would ask his little girl to carry such a load. It's the same way, Corrie, with knowledge. Some knowledge is too heavy for children. When you are older and stronger you can bear it. For now you must trust me to carry it for you.”

And I was satisfied. More than satisfiedâwonderfully at peace.

There were answers to this and all my hard questionsâfor now I was content to leave them in my father's keeping.

E

VENINGS AT THE

Beje there was always company and music. Guests would bring their flutes or violins and, as each member of the family sang or played an instrument, we made quite an orchestra gathered around the upright piano in Tante Jans's front room.

The only evenings when we did not make our own music was when there was a concert in town. We could not afford tickets but there was a stage door at the side of the concert hall through which sounds came clearly. There in the alley outside this door, we and scores of other Haarlem music lovers followed every note. Mama and Betsie were not strong enough to stand so many hours, but some of us from the Beje would be there, in rain and snow and frost, and while from inside we would hear coughs and stirrings, there was never a rustle in the listeners at the door.