The History Buff's Guide to World War II (17 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

During the war, the U.S. Navy built nearly three times as many fleet carriers as did the Empire of Japan.

The carrier USS

Franklin

was a tough nut to crack. In October 1944, over a period of two weeks in the Philippines, she was hit by a kamikaze, a bomb, and another kamikaze. Sent to the United States for repairs, she returned to the Pacific in time for the Okinawa campaign only to be hit by two more bombs and set on fire. But the carrier never sank.

10

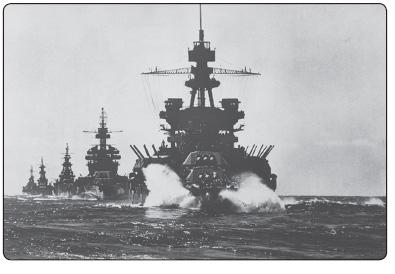

. BATTLESHIPS (50)

Bismarck

,

Arizona

,

Prince of Wales

,

Yamato

—it is sad yet symbolic that the most famous battleships were all sunk. For centuries, battlewagons were the prestige and soul of the major navies, and there was no reason to believe otherwise when the Second World War began.

At the height of their influence, the

Arizonas

of the world were appropriately called “capital ships,” top of the line. Brandishing the largest guns and heaviest armor of anything afloat, they were born to fight other ships for control of the seas, thus their deaths were often interpreted as a serious if not mortal blow to a nation’s naval strength.

By the time the conflict officially ended—ironically on the deck of a battleship—it was patently obvious that the grand vessels no longer ruled the waves. In a way, the aforementioned battleships demonstrated the paradigm shift. All four were sunk in part or completely by aircraft.

Just weeks before December 7, 1941, a U.S. Navy publication boasted that America had never lost a battleship to air attack.

Given few opportunities to sink enemy ships, crews adapted to new assignments, primarily battering land targets and protecting aircraft carriers. Direct attacks on other fleets were rare. During the war, U.S. battleships exchanged salvos with enemy vessels in only three engagements: Casablanca, G

UADALCANAI

, and

LEYTE GULF

. One of several naval actions at Leyte Gulf involved the battle of Surigao Straight, in which Japanese and American armadas traded fire in the early morning hours of October 25, 1944. The fight ended when the imperial battleship

Yamashiro

sank from torpedo hits. The USS

Mississippi

trained its big guns on the dying vessel and fired its first and only volley of the affair. It was the last time in history a battleship ever fired on another. Confirming the end of an epoch, the shots missed.

28

The four largest American battleships ever made—the

Iowa, Missouri, New Jersey,

and

Wisconsin

—never took part in a surface engagement during the entire war.

ITEMS IN A SOLDIER’S DIET

The foundation of morale, food was also the primary determinant of how far troops could march, how fast they could act, how quickly they could recover, and how well they could maintain discipline. The U.S. Quartermaster Corps categorized rations as “Class I,” ahead of fuel, clothing, ammunition, and everything else. In 1940 dollars Lend-Lease sent $5 billion in aircraft and $5.1 billion in food.

29

Rations were also a direct reflection of a country’s ability to wage war. If a link in the food chain broke—such as loss of farmland, surrender of rail lines, or failure of organization—it meant that military and civilian populations did not eat. With their shipping lanes cut, Japanese soldiers stationed on G

UADAICANAL

began to call it “Starvation Island.” Conversely, Allied advances on Germany from both the east and west stalled in late 1944 because they outran their supply lines. German soldiers lost ground in the east about the same time their rations began to perceptibly decrease.

On average, Chinese and Japanese troops were among the poorest fed, and Americans were by far the best supplied. Yet persons aboard ships always had to carefully ration goods, and field units at any moment could find themselves vainly searching for mobile kitchens. Many veterans recalled days when there was nothing to eat, leaving every moment occupied with thoughts of food.

Listed below are the fodders of fighting men, particularly concerning ground troops. Items are ranked by the quantity generally consumed.

1

. WATER

A Japanese military training manual stated it bluntly: “When the water is gone it is the end of everything.” A soldier could (and many did) survive days without food, but as the booklet added, “Water is your savior.”

30

Men stationed in North Africa or the South Pacific were extremely susceptible to abrupt dehydration, resulting in cramps, headaches, fatigue, sometimes delirium, and sunstroke. In jungle operations, the Japanese calculated that a man required nearly two gallons per day (and a horse could need up to fifteen gallons).

In most regions, water was available. But the problem was fresh water. Oceangoing vessels were in transit for weeks at a time, requiring sailors and passengers to persist on two glasses a day. Snowbound troops at least had a ready supply, provided a fire could be made. In warmer weather, sources near campsites usually contained high concentrations of bacteria, made worse by bathing and the lavatory habits of animals as well as men. Water in combat areas was generally unusable due to spilled fuel and rotting corpses.

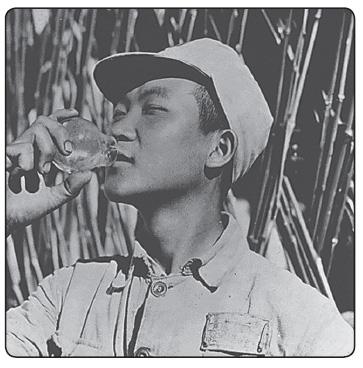

A Chinese laborer uses a light bulb as a drinking glass

Purification came through filtering and boiling. There was also the use of creosote pills or chloride of lime, which permeated every drop with an acrid taste. To make chemically treated sources palatable, Europeans often carried “fizz tablets” (vitamin-enriched bicarbonate flavor capsules). Americans received lemon-flavored powders in their rations, which the men universally hated, until they tried it with hard alcohol.

31

Only a few wells existed on the volcanic ash island of Iwo Jima. All stank of sulfur, yet the Japanese depended on them for survival. Some of the last Imperial assaults made in the battle were failed attempts to retake two wells lost early to U.S. Marines.

2

. BREAD AND RICE

G.I. Joe had white. Ivan and Jerry ate rye. Tommy had his royal wheat. More than half the Japanese diet was based on rice. As the eternal staple, grain fueled the armies of the world, and most countries aimed to provide two pounds of grain per soldier per day.

32

Installations and cities usually provided numerous bakeries, but frontline activities normally required mobile kitchens. In Europe, Americans adopted the British field kitchen. If the weather was cooperative and supplies adequate, a single German field bakery with a few dough mixers and ovens could produce enough to feed ten thousand men a day.

33

When fresh loaves were unavailable, the aptly named hardtack became a necessity. Weighing a few ounces each, biscuits, crackers, and blocks appeared in C-and Krations, tins, plastic, paper, or crates. Usually old and stale, they hurt the jaw and clogged the stomach. Spreads were minimal. Americans sometimes received margarine, which tended to be more like a petroleum by-product. Europeans had jams and marmalades when they were lucky, animal lard (a.k.a. drippings) otherwise, but they frequently had nothing except the dry, coarse brick itself.

By 1944, U.S. forces stationed in the European theater consumed eight hundred thousand pounds of bread every day.

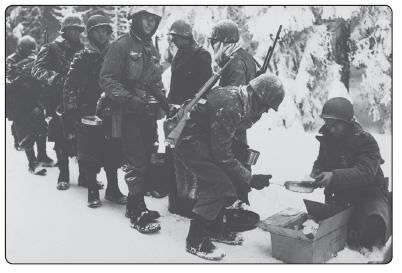

3

. SOUP AND STEW

As roasting or grilling took too long to feed thousands at a time, mobile kitchens were designed primarily for boiling. There were porridges of oats, barley, or corn. Russians ate “Kascha” mush and pickled beat borscht. When preserved or frozen beef could be found, the English had Irish stew. The Japanese drank something that loosely translated as “weed soup.” Nearly every army fried broth cubes as a substitute when meat or vegetables went missing in action.

34

Hot meals in wintertime were key to maintaining troop morale.

The universal stereotype of the surly, cold, and indifferent army cook is based largely in fact. The first to hear the soldiers’ complaints and the last to control the supply chain, cooks and mess sergeants were often driven to exhaustion while feeding the conveyer belt of impatient mouths. Either making too little or too much food, most started work well before sunup and finished long after sundown. Some combat soldiers thought highly of their commissary chefs, especially the ones who would brave enemy fire to feed the men. Overall, the hardest-worked and least-liked men in the unit were saddled with as much responsibility as officers, but with none of the perks.

During winter on the eastern front, soldiers on both sides recalled seeing bowls of boiling soup freeze solid within two minutes.