The History Buff's Guide to World War II (18 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

4

. CANNED MEAT

Watertight, dividable, and easily shipped and stored, canned meats were a modern convenience for commissary officers. Distributed when operations were in motion, the tins had a varied reputation among the grunts. Unlike square ration packages with dried food, cans were awkward and heavy to carry. If served hot, the contents were tolerable. Taken cold, all had the taste and texture of chunky sludge.

Until 1945 Cration meals (twelve-ounce cans) embodied monotony. There were meat and beans, meat and veggie hash, or meat stew. Germans muscled down their “iron ration” of hardtack and canned pork. Troops of all nationalities disliked corned beef or “bully beef.” The runny brown botch of gravy and gristle earned the nicknames “dog food” and “kennel rations.”

So overrun with Spam during their stay in England, U.S. servicemen referred to the country as Spamland. But many Yanks tolerated the meatlike loaf in lieu of canned British alternatives such as bacon and liver, fish and egg, or meat and kidney pudding.

35

Canned fish was prominent in non-American diets. Commonwealth troops had salmon, mackerel, herring, and sardines. The Japanese consumed large amounts of tinned sea eel. Pushing into the Third Reich, hungry American soldiers captured a cache of German canned fish that was oddly gray and flavorless.

36

Sometimes the troops had no idea what they were consuming. Rain-soaked, sunbaked, and oft-handled cans frequently lost their labeling. Others had ambiguous markings like MV for “meat and vegetables.” Unfortunately, opening the containers did not always solve the mystery.

Afrika Korps troops ate cans of meat stamped “AM.” German troops claimed it meant “Alter Mann” for “old man.” Italian infantry surmised the initials stood for “Asino Morte” for “dead monkey.”

5

. VEGETABLES

Soldiers received fewer fresh vegetables than they did in peacetime. Soybeans and bean paste were staples for many Japanese Imperial soldiers, eaten less often but providing far more nutrition than rice. Short on meat, Soviets and Eastern Europeans lived on beets, turnips, cucumbers, and cabbage. While Americans consumed large quantities of corn, Germans were less inclined, as they traditionally viewed maize as pig food.

37

The exception was potatoes, sweet and white in the East, every other variety in the West. For most armies, spud consumption outweighed all other veggie intake combined. In search of a little variety, some stationary units were able to grow their own crops. Allies camped in Britain sowed thousands of acres of peas, carrots, and onions.

38

The Japanese government encouraged its armies to be “self-sufficient” in their respective theaters, buying or taking what they needed from surrounding areas. The order was easy to follow on the Asian mainland, as Imperial troops held the most productive regions. Life on the Pacific islands was a different matter. The Japanese planted crops just to survive, but volcanic soils and rocky terrains made for poor yields. Shortages and malnutrition plagued garrisons consistently in these areas.

39

Airmen everywhere learned quickly to avoid most vegetables as well as any food that caused gas. Not a serious problem back at the base, intestinal gas expanded at altitude in nonpressurized aircraft, causing great pain and occasionally serious internal damage.

6

. TEA AND COFFEE

A national right among Commonwealth soldiers, Russians, and the Japanese, tea was also the most favored weapon against unsavory water. It came in nags, bulk, cakes, and slabs. The British developed palm-sized “tea tablets” called Service Blend Compressed, which usually sported a bit of a rotted scent and savor. Russians and Chinese usually received miniscule amounts in loose, coarse form. Many Commonwealth charges had the pleasure of getting sugar and dried milk with their ration, but fresh milk was a rarity throughout the war. Sweetened condensed milk was as good as gold, particularly in the China-Burma-India theater.

No nationality downed coffee like the Americans, who continually requisitioned their quartermasters for more. Airmen and sailors had a greater take, while ground troops on the move had to settle for condensed coffee in the C-and Krations. When torn up and burned, the wax and paper boxes of Krations usually gave off enough heat to warm a cup or two of joe.

For fresh-ground java, fuel supplies had to be taken into consideration. Mobile coffee production usually required coal-powered roasters and gasor diesel-driven grinders.

7

. FRESH MEAT

When it was on the menu, things were either going very well or very poorly. American troops on the island fortress of Britain sometimes enjoyed a slice of beef and tried to develop a taste for mutton. Most airmen regularly received hot meals with servings of fowl or red meat. This luxury was partly due to the relative permanence and security of air bases and partly because of their line of work, which required good food and plentiful rest to operate their extremely complicated and expensive machinery. Line troops also had the occasional pleasure of dining on something that wasn’t canned, pickled, smoked, salted, frozen, or puréed, usually because of a respite in the fighting and open supply lines.

Then there were times when necessity was the mother of ingestion. Poisonous snakes were standard fare to a few jungle-bound troops. Japanese enlisted were instructed to eat the snake liver raw for its nutrients. On several fronts, rats and dogs made their way to the dinner table. When in hurried attack or retreat, cooking was not always an option. Several American units in the Battle of the Bulge recalled catching farm chickens and eating them freshly plucked. One lieutenant lost in Burma recalled surviving a month solely on bamboo, parsley, and lizards. Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, in command of the courageous defense of the Bataan Peninsula in the spring of 1942, ordered his starving men to slaughter indigenous water buffalo, later their own horses, and finally their army mules. Horses, being a major form of transportation on the eastern front, also became a frequent part of diets.

40

In his failed invasion of India, Japan’s Gen. Mutaguchi Renya figured he could feed his troops by bringing along goats, cattle, and water buffalo. After most of his “rolling stock” died or disappeared along the treacherous march, his men were reduced to eating grass and monkeys.

8

. SWEETS

Issued for their high-caloric content and mild stimulant qualities, sugar-laden foods appeared frequently in the hands of Westerners. Conversely, loss of sugar beet and sugar cane crops greatly reduced confectionary opportunities in the East.

Chocolate candies and drinks, chewing gum, and sugar cubes were most common in the European theater. Germans enjoyed brief periods of plentiful chocolate, until they ventured farther east and the confection disappeared from view. A standard in the American kit was the Dration, a single bitter candy bar also known as the Logan Bar. Appropriately, American soldiers each carried a Dration on D-day. To be eaten when nothing else was available, the carbo-loaded snack usually consisted of oatmeal, cocoa, sugar, and dried milk. Chalky and concentrated, it was hard to chew and even tougher to pass.

41

Nothing brought out fresh food like the liberation of small villages and towns.

Dairy-based treats did not fare well in the tropics. Instead, fruit bars, cereal bars, and hard candy were standards among the Allies. Australian rations contained appropriately named “musk lozenges,” odiferous little bonbons with a sweet, syrupy taste. Initially most candies were generic in label and flavor, but by 1943 the Allies were seeing and eating a greater number of major brands. By the end of the war, the Japanese rarely ate processed sugar. More than any other commodity, sugar vanished from Japanese warehouses and homes. From Pearl Harbor to the fall of Okinawa, imports fell 80 percent and production essentially stopped.

42

By 1944, Lend-Lease was feeding the Soviet war machine large quantities of Krations filled with brand-name candy, providing many Communists with their first and last taste of Hershey, Pennsylvania.

9

. ALCOHOL

Just a decade out of Prohibition, U.S. conscripts were surprised by the amount and variety of spirited beverages overseas. They tried to develop a taste for hearty Irish and English stouts, preferring the ales, and choked on whiskeys when they could get some. American naval personnel, forbidden from having drink on board, were comparatively grateful for whatever was available on land.

The march through Northern Europe provided Americans with a veritable tour of spirits. Accepted from grateful locals, “found” in cellars, or slammed in off-duty escapades, G.I.’s had cider in N

ORMANDY

, champagne in Champagne, beer in Holland, and schnapps in Germany.

43

For the most part, the soldiers were not after the taste. Alcohol quenched a fierce thirst, especially in areas where clean water could not be found. More often, Americans were drinking for the same reasons as their brothers in arms. Ever since the Great War, the British knew the benefit of a rum ration in times of combat. The French and Italians, accustomed to wine since childhood, switched to harder drinks when called for. A German soldier marching through Belgium in 1940 admitted, “Only through alcohol, nicotine, and that never-ending, ear-deafening raging and roaring of the guns are you still able to remain upright.”

44

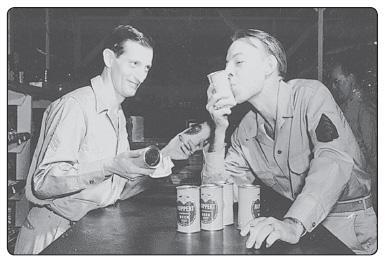

Two U.S. sergeants display their affection for beer.

In lieu of physical escape, combatants often turned to drink in search of calm, or courage, or to momentarily feel nothing. Drunkenness skyrocketed among Soviet soldiers before they headed into combat. Consumption on the frozen steppes sometimes reached a quart of vodka a day. German troops disillusioned by the war referred to alcohol as Wutmilch, meaning the “milk of fury.” Wounded and dying Japanese on Saipan slammed lethal levels of sake then hobbled away in the largest banzai attack of the war. One soldier said of drink, “It is the easiest way to make heroes.”

45

When they could not find alcohol, the troops tried to make it, or at least something with a similar effect. Members of a U.S. infantry unit in Germany attempted to get a buzz by mixing grapefruit juice with antifreeze. Soviet soldiers in Stalingrad filtered antifreeze through gas mask filaments then drank it straight. Many went blind.

10

. FRUIT

A lack of refrigerated ships, boxcars, and trucks made fresh fruit impractical for field operations. Most of the time, supplies had to be requisitioned, bought, or taken from nearby growers. Marchers ate melons in Sicily, apples in Germany, grapes in France, and dates in Greece, but little of it seemed to fill stomachs. Soldiers and sailors in the tropics gathered pineapples and coconuts for the half-pint of juice inside.

46

For the leaner months, there were small amounts of preserved fruit. Russians ate dried apricots and raspberries. The Japanese had salted plums. The British supplemented with canned fruit puddings or fruit salads. Americans hesitantly consumed a fair amount of prunes, also known as “Army strawberries.”

47

Though servicemen could live without the bland flavors of dried and salted fruits, they could not live well without the vitamins therein. Absences of B and C were of high concern to medical personnel. Recent inventions of vitamin pills were of marginal help to the worst cases of deficiency, which tended to fall easy prey to the diseases of dysentery and scurvy.

48