The History Buff's Guide to World War II (37 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

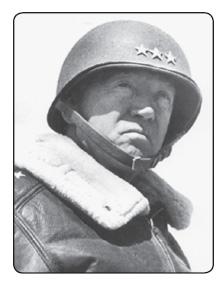

Assigned to lead the U.S. assault on Casablanca in the 1942 Allied invasion of North Africa, Patton secured the area in less than a week. He took over the U.S. Second Corps after its demoralizing defeat in Tunisia, quickly establishing discipline and morale. Leading the U.S. Seventh Army in the invasion of Sicily, Patton and his troops traveled twice as far and twice as fast as the British, securing most of the island in less than a month.

Two separate incidents in Sicily, one of which was heavily publicized, nearly wrecked Patton’s career. He verbally and physically assaulted two soldiers suffering from combat fatigue, and the public backlash greatly embarrassed the U.S. high command. Biographers commonly refer to Patton’s outbursts as temporary “meltdowns” on the general’s part. Viewed on the whole, his outbursts epitomized his character. Willful and belligerent, Patton neither understood nor tolerated hesitation in combat. His aggressiveness (which Gen. D

WIGHT

E

ISENHOWER

worked diligently to harness) was a constant mental state, one that handicapped him on a personal level but empowered him in command.

51

Patton redeemed himself at the head of the U.S. Third Army in France. Activated seven weeks after D-day, his men swept west and secured most of the Brittany Peninsula, then raced east on an abrupt charge to the German border. The surprise German offensive in the B

ATTLE OF THE

B

ULGE

failed in large part because Patton cut it off at its base. In the advance into the Third Reich, Patton’s was the most successful army in grabbing territory, plowing through southern Germany and seizing parts of Austria and Czechoslovakia before being ordered to halt. In less than a year his men advanced more than one thousand miles across enemy-held territory, moving farther and faster than any other unit in the operation.

Patton survived the war but was mortally injured in a car accident in Germany months after the peace.

Having served his country in Mexico, World War I, and World War II, George S. Patton Jr. also donned a U.S. uniform in the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, where he finished fifth in the modern pentathlon.

10

. BERTRAM RAMSAY (UK, 1883–1945)

Ramsay was humble and diligent among his peers yet venomous against incompetents. A naval veteran of the First World War, Bertram Ramsay came out of retirement to serve as the ranking flag officer at Dover. It was from this channel city, from tunnels beneath Dover Castle, that Ramsay and his staff directed the emergency evacuation of British, French, and other troops from embattled Dunkirk. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, himself a former lord of the admiralty, estimated 45,000 troops could be saved. Sailors, the RAF, civilians, and Ramsay rescued more than 330,000.

52

Duly knighted for his actions, Ramsay was later the deputy naval commander of the invasion of North Africa. The task was at best daunting, requiring the transfer of U.S. soldiers from New York directly to Casablanca and the passing of more than 300 British ships through the Straits of Gibraltar. Out of all the vessels, the Allies lost only one transport and landed more than 65,000 troops. Ramsay also served as deputy commander in the amphibious invasion of Sicily in 1943, involving nearly 2,600 ships tasked with escorting soldiers ashore.

In 1944, Ramsay was in charge of Operation Neptune, the naval portion of the N

ORMANDY

invasion. Pulling together battleships, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, tugs, hospital ships, minesweepers, landing craft, and other vessels (totaling four thousand ships, mostly British), loading divisions from across the English southern coast, rendezvousing the armada in the Channel, and directing it across hostile waters, Ramsay and his subordinates delivered five divisions to the northwest shores of occupied France.

Under Ramsay’s guidance, the Allies hauled and assembled two artificial ports, laid an underwater oil pipeline, and shuttled more than seven hundred thousand men plus vehicles and supplies in a matter of weeks. Longtime friend of Winston Churchill, object of esteem among servicemen of all ranks, the steadfast Ramsay helped orchestrate the largest amphibious invasion of all time.

53

Adm. Sir Bertram Ramsay did not get to see the fruition of his great efforts. The day after New Year’s 1945, en route to a meeting with Field Marshal Montgomery, Ramsay died when his plane went down over France.

WORST MILITARY COMMANDERS

The fortunes of war can tarnish the finest brass, just as misfortunes, extenuating circumstances, and politics can negate diligent and able service. RAF air chief Marshal Hugh Dowding saved Fighter Command, and possibly England, by using his pilots sparingly in the B

ATTLE OF

B

RITAIN

, but his shrewd methods won few fans, and he was removed from his post. Lt. Gen. Walter Short and Adm. Husband Kimmel, both competent and professional soldiers assigned to command in Hawaii, were made to take the blame for the damage leveled on P

EARL

H

ARBOR

.

But there were chieftains who had no excuse, who repeatedly wasted, endangered, and failed their countrymen despite being given liberal amounts of public support, military hardware, skilled subordinates, ample I

NTELLIGENCE

, time, and virtual autonomy of command. Following are ten prime examples of habitual underachievers among the high-ranking, selected for the degree to which they squandered chances, created problems, and generally contributed to their nation’s demise.

1

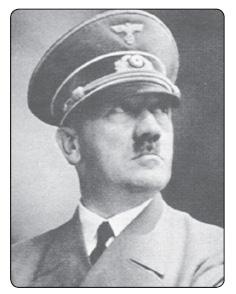

. ADOLF HITLER (GERMANY, 1889–1945)

In a decade he took a minuscule army in a bankrupt country and developed it into the strongest and most feared military power in the world. Had he only stopped after the defeat of France, he might have been heralded as the brightest military mind of the twentieth century. But the halcyon days after the armistice of Compiègne soon faded into darkness as Hitler began to exercise an unnatural degree of control over a system fraught with limitations, and few components of Hitler’s war machine were more limited than himself.

Though a gifted orator, Hitler was a phenomenally poor communicator. He preferred to lecture rather than listen. He gave vague orders, refused to delegate tasks, and invalidated opinions divergent of his own.

On military concerns, he was almost completely ignorant of air and naval operations. Logistics confused him. He assumed any shortage of fuel or ammunition was a matter of supply rather than transportation. Strategically he had a strange habit of halting offensives just before they reached their objectives, demonstrated outside of Dunkirk in 1940 and within miles of Leningrad in 1941.

If Hitler did not know when to move forward, he also refused the option of pulling back. He first issued a “no retreat” order in November 1941 to tank commanders in the Caucasus. He would repeat the directive for the rest of the war, dismissing or executing any general who moved anywhere but forward.

54

When men failed him, Hitler placed an increasing faith in machines. By 1943 he assumed the next V-weapon or supertank was all that was required to reverse his losses. As with logistics and people, he did not understand the limitations of technology. He once demanded the construction of a missile with a ten-ton warhead. A rocket engine capable of such thrust would not exist for another twenty years.

55

Examples abound of his miscalculations, baseless reprisals, and ever-widening separation from reality. Arguably his weakest characteristic as a military commander was his vacillation, notably pertaining to war aims, indicating that this leader of the “master race” had no master plan.

56

For his tombstone, Hitler stated he wanted the epitaph: “He was a victim of his generals.”

2

. HERMANN GÖRING (GERMANY, 1893–1946)

On top of his corpulent ego, his unceasing repression of political opponents and Jews, and his art pilfering, narcotics bingeing, palace squatting, jewelry hoarding, and other related acts of Nero-esque debauchery, Hermann Göring was also a bungling air force officer.

A World War I flying ace and last commander of the Richthofen Squadron, the starved-for-action Göring joined the fledgling Nazi Party in 1922 and quickly climbed its ranks. In 1935 Hitler named him Luftwaffe commander in chief. Heading the most technical branch of the German armed forces, Göring had little understanding of engineering and production. He once said half-jokingly that he did not know how to operate his radio.

57

Göring summarily appointed yes-men and incompetents, failed to develop an operational long-range bomber, and led his Führer and country to believe the Luftwaffe could achieve anything. Initially it could. The Luftwaffe was exceptionally effective in bombing the undefended city of Warsaw in 1939. After the action, Göring received the fabricated übertitle of Reichsmarshal.

58