Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

The History of White People (29 page)

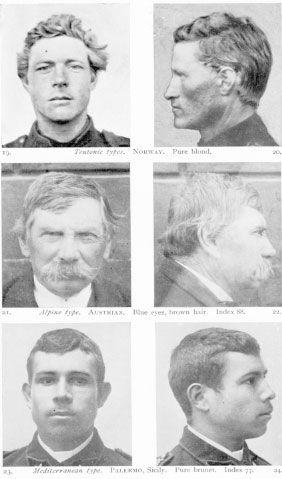

The three types are ranked vertically, with the Teutonic inevitably at the top, the Mediterranean inevitably at the bottom, and the Alpine in the middle. The Alpine type’s cephalic index is noted as 88, that is, brachycephalic, and the Mediterranean type’s as 77, that is, dolichocephalic, and the hair and eye color of both types is noted. The two dolichocephalic Norwegian Teutonic types are simply “pure blond,” although, inexplicably, the hair color of the man on the right seems as dark as that of the brachycephalic Austrian and the Sicilian.

The four men depicted as embodiments of the “Three European Racial Types” have no names. Anthropologists of the era saw no need for names. They dealt in ideal “types” that stood for millions of presumably interchangeable individuals.

Fig. 15.4. “The Three European Racial Types,” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

R

IPLEY’S

624 pages do contain a great deal of information—unfortunately, much of it is contradictory. He recognizes early on that his three racial traits—hair color, height, and cephalic index—are not reliably linked in real people. Short people can be blond; blond heads can be round; long heads can grow dark hair. He admits—and laments—that such complexity destroys any notion of clear racial types. Even his limited number of traits produced an infinity of races and subraces, a taxonomical nightmare.

*

To further undermine notions of racial permanency, Ripley concedes that mixture and environment, which most anthropologists preferred to ignore, also affect appearance. Faced with such complexity and so many unknowns, Ripley was, he says, “tempted to turn back in despair.” But he could not let go.

8

He did, however, turn his back on the American South, where people white in appearance were discriminated against as Negroes. The U.S. Supreme Court had taken that matter up in

Plessy v. Ferguson

in 1896. Homer Plessy, a man who looked white, had been ejected as black from a newly designated white-only car. He sued and lost when the court ruled for segregation. The African American novelist Charles Chesnutt remarked on the “manifest absurdity of classifying men fifteen-sixteenths white as black,” but, absurd or not, that was long to hold true.

9

*

Ripley hardly cared. What happened in the South was less important than how to classify the immigrants pouring into the North. To unravel black and white would have hopelessly snarled his system.

Additional conceptual problems haunt the book’s organization. Definitions—who counts as European people and what constitutes European territory—conflict from one chapter to the next. Ripley is not sure where Europe and its races begin and end. While he dismisses Blumenbach’s notion of a single Caucasian race,

The Races of Europe

reaches past the territory of the Teutonic, Alpine, and Mediterranean races into Russia, eastern Europe, and western Asia as far as India. Africans appear in the chapter on Mediterranean race. Supposedly the Teutonic race belongs in Scandinavia and Germany; the Mediterranean race, in Italy, Spain, and Africa; and the Alpine race, in Switzerland, the Tyrol, and the Netherlands. Yet another, separate chapter wonders whether Britons originated in the Iberian Peninsula, given that Irish legend names the Spanish king Melisius as the father of the Irish. More taxonomical strangeness was to come.

A

S NOTED

, Ripley’s three-race system excludes many Europeans, such as Jews, Slavs, eastern Europeans, and Turks. Lapps present the usual quandary: they obviously live in Europe, but they do not look the way anthropologists wanted Europeans to look. Linguists did not face this problem; they put Lapps with Magyrs, Finns, and other speakers of Finnic languages. No problem there. But Ripley rejects this linguistic classification because the Lapps lack beauty: “The Magyrs, among the finest representatives of a west European type,” he says, “are no more like the Lapps than the Australian bushmen.” (See figure 15.5, Ripley’s “Scandinavia.”) The captions under photos of Lapps list only height (4’ 9½” and 4’ 8”) and high cephalic indexes (both 87.5) as confirmation that Lapps are too short in stature and too broad of head.

10

*

Piling it on, Ripley adds an unnamed German anthropologist’s insult that “they [Lapps] are a ‘pathological race.’” Actually, rather than documenting pathology, these photographs demonstrate a Scandinavian variety trumped by racial science’s obsession with purity.

Fig. 15.5. “Scandinavia,” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

J

EWS POSE

another problem. Having long occupied a separate conceptual space within the races of Europe, they must be discussed as a category. At the same time, they are too varied to fit into one of Ripley’s three European races. Recognizing this shortcoming early, Ripley had added a “supplement” on Jews to his Lowell Institute Lectures and articles published in

Popular Science Monthly

.

The Races of Europe

allots Jews and Semites a separate chapter.

Fig. 15.6. “Jewish Types,” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

Anti-Semitic writers had long posited a permanent Jewish race. But Ripley does not like that. Rather, he calls them a “people,” since Jews conform closely to others among whom they live. His photographs of Jewish faces confirm regional variation.

11

*

(See figure 15.6, Ripley’s “Jewish Types.”)

Then consider their noses. Ripley’s bizarre discussion of the stereotypical Jewish nose betrays his uneasiness. He draws three figures to demonstrate how easily “the Jew” may be turned into a Roman. (See figure 15.7, Ripley’s “Behold the Transformation!”) A tortured paragraph explains this conceptual nose job:

The truly Jewish nose is not so often truly convex in profile. Nevertheless, it must be confessed that it gives a hooked impression. This seems to be due to a peculiar “tucking up of the wings,” as Dr. Beddoe expresses it…. Jacobs has ingeniously described this “nostrality,” as he calls it, by the accompanying diagrams: Write, he says, a figure 6 with a long tail

(Fig. 1); now remove the turn of the twist, and much of the Jewishness disappears; and it vanishes entirely when we draw the lower continuation horizontally, as in Fig. 3. Behold the transformation!

Throwing up his hands, Ripley also explains that Jewish noses do not prevail among urban Jews; besides, many non-Jews have noses that look Jewish.

12

T

ODAY’S READERS

might find intriguing Ripley’s use of a measure of blackness for people of the British Isles. His tool, the “Index of Nigrescence,” had originated with the respected British anthropologist John Beddoe. Over the course of thirty years, Beddoe measured thousands of British heads. Employing impeccable methodology, he analyzed their cephalic indexes, hair, eye, and skin color. Those measurements grounded his classic

Races of Britain

(1885), whose countless pages of tables convinced Ripley and his generation of scientists that the Irish were dark. Beddoe’s maps and photographs slipped easily into Ripley’s chapter on Britons in

The Races of Europe.

13

(See figure 15.8, Ripley’s “Relative Brunetness.”)

Fig. 15.7. “Behold the Transformation!” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

The text reads, “RELATIVE BRUNETNESS BRITISH ISLES, after Beddoe ’85 [

Races of Britain

] 13,088 observations.” On the right the scale ranks the “INDEX OF NIGRESCENCE,” with light skin and hair at the top and dark skin and hair at the bottom.

This map also attempts to define linguistic groups: a line between highland and lowland Scotland traces the boundary of the Gaelic speech of Scotland and Ireland (“Gaelic Celtic”); another line separates English from the Gaelic of Wales and the Channel Islands (“Kymric Celtic”); a line through Ireland demarcates the eastern borderline of Irish Gaelic. These unreliable linguistic boundaries often reappeared as racial boundaries between Briton and Celt. Lowland Scots such as Thomas Carlyle and Robert Knox, you may recall, were delighted to be British Saxons rather than highland Scottish Celts.

R

ACES OF

E

UROPE

vaulted to success immediately on publication in 1899. The

New York Times

devoted two full pages to a glowing review, reproducing several of the book’s photographs. The

Times

reviewer (identified simply as W.L.) raves about Ripley’s “great work” of “elaborate scope and exhaustive treatment.” Best of all, Ripley demolished the “schoolroom fallacy that there is such a thing as a single European or white race.”

14

Addressing general readers, the

Times

underlines this telling point in an era of alarming European immigration. Scholars also loved

Races of Europe

. The sheer amount of labor it required delighted the

American Anthropologist

’s reviewer, who gushed over “the best results of the last twenty years in physical anthropology.”

15