Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

The History of White People (30 page)

Fig. 15.8. “Relative Brunetness British Isles,” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

The British edition of 1900 prompted the Royal Anthropological Society to give Ripley anthropology’s crowning honors, the Huxley Medal and an invitation to deliver the Huxley Lecture of 1902. Occupied with a move from part-time appointments at MIT and Columbia to a permanent post at Harvard, Ripley was unable to accept for 1902. Later he remarked with youthful hubris that Sir Francis Galton, the world’s most famous statistician—and the father of eugenics—had substituted for him.

16

Ripley did finally deliver the 1908 Huxley Lecture, the first American to achieve this singular mark of distinction. The

New York Times

reported his lecture under the pithy headline of “Future Americans Will Be Swarthy.”

17

Like

Races of Europe

, Ripley’s Huxley Lecture delivers racist notions in scholarly tones.

*

He predicts a “complete submergence” of Anglo-Saxon Americans to follow the “forcible dislocation and abnormal intermixture” of many races and the low Anglo-Saxon birthrate. He also frets that Jews (“both Russian and Polish”) were dying at too slow a rate, “only one-half that of the native-born American,” despite living in abysmal circumstances. While Anglo-Saxons avoided having children, short, dark, round-headed Jews in the tenements multiplied alarmingly. Echoing his mentor Francis Amasa Walker’s phrasing, Ripley warns that immigration was now tapping “the political sinks of Europe,” bringing a “great horde of Slavs, Huns and Jews, and drawing large numbers of Greeks, Armenians and Syrians. No people is too mean or lowly to seek an asylum on our shores.”

Reiterating favorite themes in European racial science, Ripley warns that the tendency of city people to be darker “can not but profoundly affect the future complexion of the European and American populations.” Ripley’s surmise that these dark-haired men were more sexually potent than blonds repeats speculations of Emerson and others, adding a note of anxiety. Ending ruefully, Ripley posits that all might not be lost. Even if Anglo-Saxon Americans followed American Indians and the buffalo into extinction, surely their mixture with others would mean a continued, worthy life. After all, there exists a “primary physical brotherhood of all branches of the white race.”

The

white race?

Dancing about the hot coals of theory in 1908, Ripley says there might be only one white race, not the three of 1899. Even further, perhaps, “all the races of men” belong to the same human brotherhood, and “it is only in their degree of physical and mental evolution that the races of men are different.”

18

If so, nevertheless, some races (the white) are more advanced—more “evolved”—than others (the dark).

This cloudy perversion of Darwinian evolution and Mendelian inheritance thrived in the early twentieth century. Like most of his scholarly peers, Ripley believed that races of people, like Gregor Mendel’s garden peas, inherited gross “unit” traits, such as intelligence, head shape, pigmentation, and height. Because Ripley believed that the original Europeans—those primitive, Stone Age Celts fated for displacement—were dark, he concludes that the “abnormal intermixture” of peoples in the United States would lead to a “reversion to the original stock.” The hybrids might be even darker than the dark parent because of “the greater divergence” of stocks. If Italian men mated with Irish women, they would produce “the more powerful…the reversionary tendency” toward darkness. There could be no intermediate pigmentation.

Harvard’s prestige played a large part in the longevity of such nonsense as scientific truth. But mostly

The Races of Europe

spoke to a race-obsessed nation by delivering the right opinions dressed up as science. Never mind that the book could not survive a careful reading, that it bulged with internal contradiction, or that its tables and maps offered a Babel of conflicting taxonomies. William Z. Ripley’s

Races of Europe

remained definitive for the next quarter century.

A

LTHOUGH

Races of Europe

defined Ripley’s reputation over the long run, it represented a detour in his scholarship, for the young Ripley had first been a promising economist rather than an anthropologist. True,

Races of Europe

brought him excellent job offers from Cornell, Columbia, Yale, and Harvard. But the position he accepted in 1902 took him into Harvard’s Department of Political Economy, where he remained until his retirement in 1933, when, like his mentor Francis Amasa Walker, he served as president of the American Economic Association.

19

In these many years Ripley’s reputation shone brightly. He appeared regularly in the

New York Times

. In the mid-1920s he warned President Calvin Coolidge, investors, and politicians of the dangers of unsound railroad financing and appeared as a cartoon character measuring railroad financial soundness. (See figure 15.9, Ripley measuring the railroads.) During the Hoover years of the Great Depression, he advocated government regulation along lines that would become President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. In fact, Ripley had taught Roosevelt at Harvard, delivering lectures that apparently inspired the reform of the American economy.

20

Through it all the

New York Times

covered him diligently, printing his warnings and reviewing his books. It reported Ripley’s auto accident, his nervous breakdowns, his retirement, his death, and, a quarter of a century later, the death of his wife.

21

All this attention signified a scholar at the top of the heap. But an immigrant of an original turn of mind was rising to challenge his preeminence.

Fig. 15.9. The

New York Times

shows Ripley measuring the railroads.

B

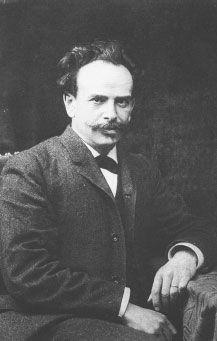

orn in Minden in Prussian Westphalia to middle-class parents, Franz Boas (1858–1942) had a sound German education. After attending a Protestant gymnasium, he studied at Heidelberg, Germany’s oldest university.

*

(See figure 16.1, Franz Boas.) Like many German undergraduates, he joined a fraternity (

Burschenschaft

) known for dueling and drinking. Interestingly, being Jewish did not stand in his way, for during the 1870s his Burschenschaft Allemannia accepted Jewish students; not until later in the century did Allemannia and other fraternities become exclusive anti-Semitic centers of German nationalism. After a semester at Heidelberg, Boas moved on to Bonn, then completed his graduate work at Kiel University, earning a Ph.D. in physics in 1881. Not that Boas escaped the barbs of German bigotry. In both Heidelberg and Kiel he had encountered Germany’s burgeoning anti-Semitism, from the “damned Jew baiters” who provoked “quarrel and fighting.”

1

By the 1880s such harassment was becoming endemic, but Boas was able to avenge these insults, at least in part, through duels that left scars on his face, symbols of honorable, upper-class German manhood.

In 1881 Boas moved on to postgraduate work at Berlin with the pioneering German anthropologists Adolf Bastian and Rudolf Virchow (the latter considered a father of German anthropology), who taught him the physical anthropology of bodily measurement and alerted him to the possible influence of environment on head shape.

2

No finer training could be had in Germany, but with anti-Semitism now closing in, his homeland hardly offered Boas a promising career. The German nationalist Berlin movement, led by its intellectual avatar, Professor Heinrich von Treitschke, had made overt hatred of Jews so widespread and respectable that Boas began to ponder emigration.

3

An opportunity arose in 1883 to pursue his study of psychophysics (the relationship between physical sensation and psychological perception) far from Germany, in Anarniturg in the Arctic Cumberland Sound. There, living with the Inuit, he sought to perceive the environment as they did and to think like them. Those two years of fieldwork were useful and enjoyable. Even the hardships and strange food came to hold an appeal. Raw seal liver, he discovered, “didn’t taste badly once [he] overcame a certain resistance.”

4

Fig. 16.1. Franz Boas.

Late nineteenth-century European anthropologists were typically both provincial and arrogant. They operated from two basic assumptions: the natural superiority of white peoples and the infallibility of elite modern science. Supposedly, scientific methodology endowed European scholars with universal knowledge. Boas might have accepted such dogma as a student, but during his time with the Inuit his independent streak took him toward diametrically opposite conclusions. Trying, for instance, to record and understand the Inuit language and failing, Boas realized that the fault lay not in the Inuit but in his own limitations. He began to see how hallowed European ways had disabled its scholars. “We [civilized people] have no right to look down on them,” he said of the Inuit, an almost unique, even heretical, thought at the time.

This breakthrough took Boas well toward the cultural relativism that would dominate twentieth-century anthropology. All knowledge, even Western knowledge, was relative and circumscribed: “our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization [i.e., our culture] goes.”

5

To know everything worth knowing was impossible. And to know anything about other people required immersion in their world, to become, in a sense, one of them.

In the decade following 1885, Boas made several fieldwork trips to the Pacific Northwest and held a series of temporary positions, including stints at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, and G. Stanley Hall’s Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, then in its heady early years. Such wandering afforded refuge from Germany and sufficient time for research, but no financial security. Finally, in 1896, at the relatively advanced age of thirty-eight, he gained an appointment as lecturer in anthropology at Columbia University, joining a faculty that included the young luminary William Z. Ripley. Not that life had suddenly become cushy for Boas. Whereas Ripley had a choice of jobs and enjoyed generous remuneration, Boas began with temporary employment and a paltry salary at Columbia, evidently made possible only by his rich uncle’s underwriting. American anti-Semitism, then on the increase, doubtless played a role in such disparity.

6

Even so, Boas quickly forged an international reputation as a careful yet innovative scholar. His colleagues soon came to respect his fieldwork and publications—they granted him tenure in 1899, when he was forty-one—even as he questioned their conventional notions of racial superiority and civilization. One such innovation appeared in Boas’s 1894 address to the Anthropology Division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, called “Human Faculty as Determined by Race.” Its premises—that race, culture, and language are separate, independent variables and should not be confused—undergirded Boas’s classic book,

The Mind of Primitive Man

, first published in 1911 and revised in the late 1930s. But as statements applying to Americans, these points began to enter popular consciousness only in the 1930s, when anthropologists were becoming the experts on race. Boas’s

Anthropology and Modern Life

(1932) then emerged as a major scientific declaration.

One theme of the 1894 lecture questioned the evolutionary view of human races that equated whiteness with development and civilization. Downplaying anatomical differences between races, Boas looked to environment and culture rather than to race as shapers of people’s bodies and psyches. Here was the radical germ of cultural relativism, one fast attracting adherents, among them Paul Topinard, successor to Paul Broca and then the leading French anthropologist. Topinard applauded Boas’s thinking, declaring him “the man, the anthropologist [he] wished for in the United States” and with whom “American anthropology enters into a new phase.” Boas, though he had not found a home in Europe, did retain some European chauvinism. He enjoyed outshining American anthropologists, who lacked his Old World education. “Actually,” he conceded, “it is very easy to be one of the first among anthropologists over here.”

7

For all its originality, Boas’s 1894 address contained a number of dated ideas. One of them was the validity of comparing numbers of “great men,” in the fashion of Sir Francis Galton in England and Henry Cabot Lodge’s “Distribution of Ability in the United States.” And Boas remained tentative, closing with: “Although, as I have tried to show, the distribution of faculty among the races of man is far from being known, we can say this much: the average faculty of the white race is found to the same degree in a large proportion of individuals of all other races, and [even though] it is probable that some of these races may not produce as large a proportion of great men as our own race.” Counting up great men might be forgiven in Boas, even inferring failure in other races and cultures. After all, such was the tenor of impeccable scholarship at the time. Everyone else was doing it, but he was moving on. Boas soon jettisoned notions of comparative intelligence, as well as designations of “higher” and “lower” races.

8

In 1906 he made another brave gesture toward racial tolerance by accepting an invitation from the pioneering African American social scientist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) to deliver a commencement address at Atlanta University. Not only was Boas a white scholar willing to go to a black institution; he came with a message of encouragement for young people about to enter a hostile America. Quite amazingly for 1906, he assured them they had nothing to be ashamed of. Other races—the ancestors of imperial Romans and the northern European barbarians—had endured their own dark ages. Now, if educated young black people could understand the “capabilities of [their] own race,” they could attack “the feeling of contempt of [their] race at its very roots,” and thereby “work out its own salvation.”

9

In these Atlanta remarks, Boas draws intriguing parallels. For instance, he likens the differences between European Jews and Gentiles to imagined racial differences between European nobles and peasants. At this time French authors like Gobineau and Lapouge, along with many other European writers, considered France’s nobility Teutonic and the common people Celts, a supposedly different and inferior race. Not so, Boas declared. European nobles were “of the same descent as the people.” So were European Jews, “a people slightly distinct in type” from the Gentiles they live among.

10

By “European” Jews, Boas doubtless had Germans in mind. In other commentary he did distance himself from Jewish immigrants newly arrived from Poland and Russia, people he termed “east European Hebrews.”

Thinking of himself as German American, Franz Boas neither hid nor proclaimed his Jewishness, and why should he have? For him, Judaism was a religion. His family, he said, had “broken through the shackles of dogma.” He had, therefore, been freed from the restraints “that tradition has laid upon us,” and could strive toward an ethical rather than a religious life.

11

There could be no such thing as a Jewish

race

, because, for Boas, race resided in the physical body, something to be measured and weighed. He placed no faith in the notions of racial temperament so dear to Ripley and his English authority John Beddoe. Boas assumed that Jewishness might eventually disappear into American society through assimilation; he and most other German Jews in the United States lived by that belief. The new Jews from Russia and Poland, however, he judged differently. Their appearance in the early twentieth century caused him some consternation.

Unable to cast out every prejudice of the time, Boas dealt with the issue of immigrant strangeness in two ways, one inclusive, the other exclusive. Obviously, American society had over many decades worked its magic, as American-born generations assimilated physically and culturally. But could it Americanize these new immigrants, “Italians, the various Slavic people of Austria, Russia, and the Balkan Peninsula, Hungarians, Roumanians, east European Hebrews, not to mention the numerous other nationalities,” and bring them closer to “the physical type of northwestern Europe”? For Boas, “these people,” so distinct in many ways, were a worrisome “influx of types distinct from our own.”

12

Here we have a contradiction. Boas did not support immigration restriction. Too much racism there. And yet his use of the language of “we” points straight to an “us” and “them” ideology. Not even this most liberal thinker could escape divisions of self and other inherent in racial ideology. The early 1900s were a particularly tough time to think about racial equality, and, as a result, such tension echoes across Boas’s work.

“H

UMAN

F

ACULTY

as Determined by Race” might strike a twenty-first-century reader as timid, even retrograde. And “your own people” addressed to a black audience in Atlanta might ring uncomfortably close to the odious “you people.” But it was dramatic to hear Boas speak warmly across the black/white color line in an era of naked racial antagonism. During the late nineteenth century, poor, dark-skinned people often fell victim to bloodthirsty attack, with lynching only the worst of it. Against a backdrop of rampant white supremacy, shrill Anglo-Saxonism, and flagrant abuse of non-Anglo-Saxon workers, Boas appears amazingly brave.

It mattered little in those times that lynching remained outside the law. More than twelve hundred men and women of all races were lynched in the 1890s while authorities looked the other way. Within the law, state and local statutes mandating racial segregation actually expelled people of color from the public realm. On a national level, the U.S. Supreme Court decided

Plessy v. Ferguson

in 1896, validating Louisiana’s railroad segregation statute and opening the way to the segregation of virtually all aspects of southern life. Such laws and decisions, allied with local practice, disenfranchised hundreds of thousands, tightening a southern grip on federal power that racialized all of national politics.

Federal policy toward Native American Indians and people from Asia also signaled their vulnerability to white cupidity. In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act, passed after loud demands from organized labor, barred any sizable immigration of Chinese workers. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor and himself a Jewish immigrant from England, clamored for Asian exclusion when the legislation first passed and when it was up for renewal ten years later. Gompers even pressed for exclusion of Chinese from settling in American Pacific island possessions and from working on the Panama Canal.

13

Before and after initial passage of Chinese exclusion, Indians and Asians in the West fell victim to whites lusting after their land and their jobs, as locals harried, attacked, and expulsed their Chinese neighbors. In 1887 the Dawes Severalty Act halved the land that Indians controlled by dividing up tribal territory among individuals and opening the so-called surplus Indian lands to white settlement. Southern states, beginning with Mississippi and South Carolina, revised their constitutions in the 1890s, encouraging the enactment of poll taxes, literacy and property qualifications, and grandfather clauses that ended black political life in the South.