The Holy Terrors (Les Enfants Terribles) (13 page)

Read The Holy Terrors (Les Enfants Terribles) Online

Authors: Jean Cocteau

“There’s a brave boy! See how casual he is!”

“Eat it yourself, you fool,” retorted Paul.

“And die of it, I suppose. Suit you fine, wouldn’t it? No, thanks, I

propose to deposit

our

poison in the treasure.”

“The smell’s absolutely overpowering,” said Gérard.

“You ought to put it in a tin.”

Elisabeth wrapped it up, shoved it into an empty biscuit tin, and vanished from the room.

The top of the treasure chest was littered with their various

possessions—revolver, books, the whiskered plaster bust; she opened a drawer and

placed the tin on top of Dargelos. Carefully, with infinite precautions, she set it

down, with a schoolgirl’s grimace of concentration; with something of the air,

the gestures of a woman pricking a wax image, aiming precisely, then ramming home the

pin.

Paul saw himself back at school again, aping Dargelos, obsessed with violence and

barbaric rites, dreaming of poisoned arrows, hoping to impress his hero by an invention

of his own, namely, a project for mass-murder by means of poisoned gum affixed to

postage stamps. And all in wantonness, without a thought of poison’s lethal

implications, all to curry favor with a lout…. Dargelos would shrug and turn

away, scornful as of a silly girl.

Dargelos had not forgotten the abject slave who once hung on his lips: this gift of

poison was the crowning stroke of his derision.

Its hidden promise filled the brother and sister with a strange elation. The room had

become richer by an extra, an incalculable dimension. It had acquired the potentials of

an anarchist conspiracy; as if a charge of human dynamite had been sunk in it, would be

touched off at the appointed hour, explode in blood sublimely, stream in the

incandescent firmament of love.

Moreover, Paul was reveling in this parade of eccentricity from which Gérard,

according to Elisabeth, wished to protect Agatha; it was a smack at Gérard, and

also at his wife.

Elisabeth, for her part, was triumphant. She saw the old Paul back upon the war path,

trampling down convention, grasping the nettle danger, jealous as ever of the sacred

treasure.

She invested the poison with symbolic properties: it was the antidote to pettiness and

parochialism; would, must—surely—lead to the final overthrow of Agatha.

But Paul failed to respond to cure by witchcraft. His appetite did not improve; listless,

apathetic, he went on pining, wasting, sinking by slow stages into a decline.

S

UNDAY was a regular

day off for the whole household, according to the Anglo-Saxon custom adopted during

Michael’s lifetime. Mariette filled the thermos flasks, cut sandwiches, then went

out with the housemaid. The chauffeur, whose duties included lending a hand indoors with

the cleaning, borrowed one of the cars and spent his time profitably, picking up casual

passengers for hire.

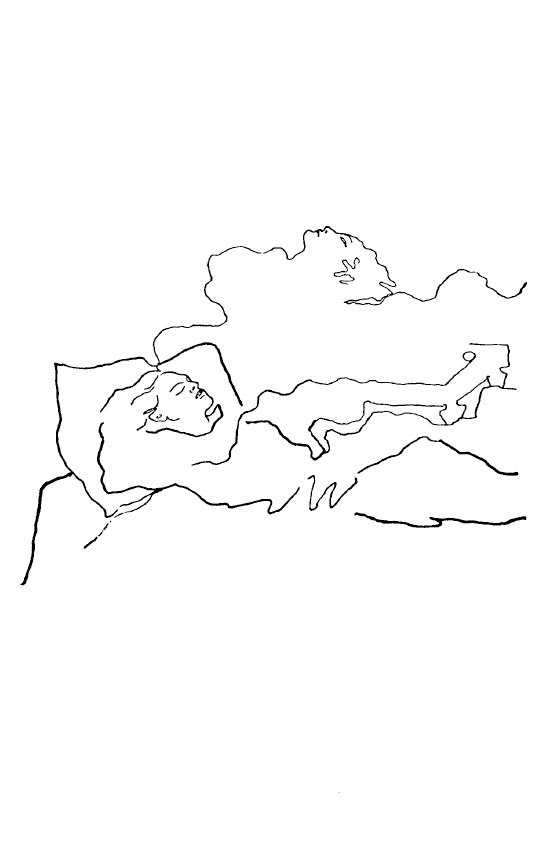

On this particular Sunday it was snowing. Acting on instructions from the doctor,

Elisabeth had gone to her own room to lie down and had drawn the curtains. It was five

o’clock. Paul had been dozing since noon. He had insisted on her leaving him

alone, had begged her to listen to the doctor. She was asleep, and dreaming. She dreamed

that Paul was dead. She was walking through a forest, but at the same time it was the

gallery; she recognized it by the light falling between the tree-trunks from tall

windows set in dark intermittent panels of opacity. She came to a furnished clearing and

saw the billiard-table, some chairs, one or two other tables. She thought: I must get to

the mound. In her dream she knew that the word

mound

meant the billiard-table.

Striding, sometimes skimming just above the ground, she made haste to reach it, but she

could not. She lay down exhausted and fell asleep. Suddenly Paul roused her. She

cried:

“Paul, oh Paul! So you’re not dead?”

And Paul replied: “Yes, I am dead, but so are you. You’ve just died.

That’s why you can see me. You’re going to live with me for ever and

ever.”

They went on walking. After a long time they reached the mound.

“Listen,” said Paul, putting a finger on the automatic marker.

“Listen to the parting knell.”

The marker began to whirr

dementedly. The glade began to hum—louder, louder, a noise like buzzing telegraph

wires….

She woke aghast, to find herself sitting bolt upright, drenched in perspiration. A bell

was pealing. She remembered that the servants were all out. Still in the grip of

nightmare, she ran downstairs and opened the front door. On a white whirlwind Agatha

blew in, disheveled, crying out: “Where’s Paul?”

By now Elisabeth had come round, was shaking off the dream’s last clinging

threads.

“What do you mean?” she said. “What’s the matter with you?

Paul’s asleep as usual, I suppose. He said he didn’t want to be

disturbed.”

“Quick, quick,” gasped Agatha, “run, we must hurry. I had a letter,

he said by the time I got it it would be too late, the poison, he’d have taken

the poison, he said he was going to shut you out of his room and take it.” She

clutched Elisabeth, pushing, pulling, trying to urge her forward. Mariette had left a

note at the young couple’s flat at four o’clock.

Elisabeth stood stock still. It was the dream, she told herself, she must be still

asleep. She was turned to stone. Then she was running. She and this other girl were

running, running.

Now she had reached the gallery, but in the dream still, she was in a spectral glade of

roaring wind and darkness, of trees whipped white in the interlucent spaces; and there,

in the distance, still

the mound

, the billiard-table, the real and nightmare

relic of an earthquake.

“Paul! Paul! Speak to us! Paul!”

There was no answer. The shining precincts gave back, for all reply, a charnel breath.

They broke in, and the full impact of the disaster hit them simultaneously. The room was

thick with an ominous aroma: they knew it—reddish, black, a compound of truffles,

onions, essence of geranium, overpowering, beginning already to invade the gallery. His

eyeballs starting from their sockets, his face distorted beyond recognition, Paul lay

supine, wearing a bathrobe exactly like his sister’s. Lamplight, snow-blurred,

eddying down through the high windows, threw gusts of shifting shadow across the livid

mask, touched nose and cheekbones into faint relief. Beside him on the chair, jostling

one another, lay the remainder of the poison, a water-bottle and the photograph of

Dargelos.

The actual tragedies of life bear no relation to one’s preconceived ideas. In the

event, one is always bewildered by their simplicity, their grandeur of design, and by

that element of the bizarre which seems inherent in them. What the girls found

impossible, at first, was to suspend their natural disbelief. They had to admit, to

accept the inadmissible, to recognize this unknown shape as Paul.

Rushing forward, Agatha flung herself on her knees beside him, brought her face close to

his, discovered that he was breathing. A flicker of hope leapt up in her.

“Lise,” she urged, “don’t stand there doing nothing, go and

get dressed, he may be only doped, this frightful thing may not be deadly poison. Get a

thermos bottle, run and fetch the doctor.”

“The doctor’s away, he’s shooting this weekend,” stammered

the wretched girl. “There’s nobody … there’s

nobody….”

“Quick, quick, get a thermos! He’s breathing, he’s icy cold. He must

have a hot water bottle, we must get some hot coffee down his throat.”

Agatha’s presence of mind amazed Elisabeth. How could she bring herself to speak,

touch Paul, how could she so bestir herself? How did she know he needed a hot water

bottle? What made her think she could prevail by commonsense against the implacable

decrees of snow and death?

Abruptly she pulled herself together, remembered that the thermos bottles were in her

bedroom. She flew to get them, calling over her shoulder:

“Cover him up!”

Paul was still breathing. Since swallowing what Dargelos had sent him, he had endured

four hours of sensations so phenomenal that he had wondered intermittently whether the

stuff was after all a drug, not poison, and if so, whether he had taken a sufficient

dose to kill him; but now the worst of the ordeal was over. His limbs had ceased to

exist. He was floating in space, had almost recaptured his old sense of well-being. But

his saliva had entirely ceased to flow, and consequently his dry tongue rasped his

throat like sandpaper; except where all feeling had become extinct, his parched skin

crawled unbearably. He had attempted to drink. He had put a faltering hand out, groping

in vain to find the water bottle. But now his legs and arms were all but paralyzed; and

he had ceased to move.

Whenever he closed his eyes, the same images reappeared: the head of a giant ram with a

woman’s long gray locks; some dead and blinded soldiers marching in stiff

military procession, slowly, then faster, faster, round and round a grove; he saw that

their feet were tethered to the branches. The bedsprings shook and twanged beneath him

to the wild knocking of his heart. The veins swelled, stiffened in his arms, the bark

grew round them, his arms became the branches of a tree. The soldiers circled round his

arms; and the whole thing began again.

He sank into a swoon, was back in the time of snow, the old days of the Game, was in the

cab with Gérard, driving home. He heard Agatha sobbing:

“Paul! Paul! Open your eyes, speak to me….”

His mouth felt clogged with sourness. His gummed-up, flaccid lips framed one word only:

“Drink….”

“Try to be patient…. Elisabeth has gone to get the thermos. She’s

bringing a hot water bottle.”

“Drink…” he said again.

Agatha moistened his lips with water. She took his letter from her handbag, showed it to

him, begged him to try and tell her what madness had come over him.

“It’s your fault, Agatha.”

“My fault?”

Syllable by syllable, he started to whisper, stammer out the truth. She interrupted him

with protestations, exclamations. The man-trap was exposed in all its tortuous

ingenuity. Together the dying man and the young woman touched it and turned it over,

unscrewed the diabolical contrivance piece by piece. Their words engendered a stubborn,

treacherous, criminal Elisabeth, whose machinations of that night were plain at

last.

“You mustn’t die!” cried Agatha.

“Too late,” he mourned.

At that moment, Elisabeth, fearful of leaving them too long alone together, came hurrying

back with the thermos and the hot water bottle. There was a moment of unearthly silence,

then nothing but the pervasive smell of death again. Elisabeth had her back turned; she

was busy hunting among boxes and bottles, looking for a tumbler, filling it with coffee,

not yet aware that all had been discovered. She advanced towards her victims, saw they

were watching her, stopped dead. By a savage and supreme effort, with Agatha’s

arms round him, her cheek against his cheek, Paul had half-raised himself among the

pillows. Deadly hatred blazed from both their faces. She held the coffee out towards

him, but a cry from Agatha arrested her:

“Paul, don’t touch it!”

“You’re mad,” she muttered, “I’m not trying to poison

him.”

“I wouldn’t put it past you.”

This was more than death; it was the heart’s death. Elisabeth swayed on her feet.

She opened her mouth, but no words came.

“Devil! Filthy devil!”

His words confirmed the worst of her suspicions and crushed her with an extra weight of

horror: she had not dreamed he had the strength to speak.

“Filthy, filthy devil!”

Over and over again, with his dying breath, he spat it at her, raking her with his blue

gaze, with a last long volley of fire from the blue slits between his eyelids. His lips,

that had been so beautiful, twisted and twitched spasmodically; from the dried well of

what had been his heart rose nothing but a tearless glitter, a wolfish

phosphorescence.

The blizzard went on battering at the windows. Elisabeth flinched, then said:

“Yes, you’re right, it’s true. I was jealous. I didn’t want

to lose you. I loathe Agatha. I wasn’t going to let her take you

away.”

Stripped, her disguise thrown off at last, she took the truth for garment; she grew in

stature. As if blown by a storm, her locks streamed back and her small fierce brow

loomed monumental, abstract, above the lucent eyes. She stood fast by the Room; she

stood against them all, defying Agatha, Gérard, Paul, and the whole world.

She snatched up the revolver from the chest of drawers.

“She’s going to shoot! She’s going to kill me!” screamed

Agatha. She clung to Paul, but he had left her side, was wandering.