The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (18 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

After a time, as Lincoln prepared to take his leave, he drew his partner’s attention to the wooden signboard swinging on rusty hinges at the foot of the stairway. “Let it hang there undisturbed,” he told Herndon in a strangely hushed voice. “Give our clients to understand that the election of a President makes no change in the firm of Lincoln and Herndon. If I live I’m coming back some time, and then we’ll go right on practicing law as if nothing had ever happened.”

Lincoln’s nostalgic afternoon with Herndon marked the end of his career as a “prairie lawyer,” though he had long since ceased to take an active role in the practice. In the previous weeks, the president-elect had spent almost all of his time laying the groundwork for his administration, assembling his cabinet, and crafting his inaugural address. Lincoln had also set his mind to the delicate task of planning his journey to Washington. After weeks of “masterly inactivity” in Springfield, Lincoln knew that every word and gesture of his reemergence into public view would be parsed for signs of how he intended to meet the secession crisis. Having invested so much care in the message of his inaugural address, Lincoln intended to tread lightly in the meantime, hoping to avoid making statements about policy until he reached Washington. In announcing the details of his inaugural journey, Lincoln emphasized that he wished to avoid elaborate ceremonies, as he knew that any suggestion of pageantry would be received poorly in the South. Even the date of departure was likely chosen with an eye to appearances. Lincoln would be well under way on February 13, the date on which the Electoral College would assemble to formally ratify his election as president. Privately, he had expressed fears that the outcome might cast doubt on the legitimacy of his election, but publicly he would signal that he considered the proceedings a mere formality.

Though he wished to avoid antagonizing the secessionists, Lincoln cannily shaped his itinerary to underscore the traditions of the presidency. The proposed route would take him through the state capitals of Indiana, Ohio, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, with stops in a number of other major cities where he had received strong support in the election. An appearance in New York City had been added to the itinerary in the latter stages of the planning, as well as a side trip to raise a flag over Independence Hall in Philadelphia, artfully timed to coincide with George Washington’s birthday.

In a sense, Lincoln was following in Washington’s footsteps. Lincoln had long admired a particular biography that described Washington’s grand procession from Mount Vernon to New York, where his first inauguration took place, and the rapturous reception he received along the way: “The inhabitants all hastened from their houses to the highways, to have a sight of their great countryman; while the people of the towns, hearing of his approach, sallied out, horse and foot, to meet him.” William Seward and others had advised Lincoln to make his way to the capital quietly, even secretly, but the president-elect believed that by traveling in an open fashion, he would lay emphasis on the continuity of the government of the United States, as well as the legitimacy of his own election.

The decision drew welcome support from Ohio governor Salmon P. Chase, another contender for the Republican presidential nomination in Chicago, whom Lincoln now hoped to bring into his cabinet. “I am glad you have relinquished your idea of proceeding to Washington in a private way,” wrote Chase. “It is important to allow full scope to the enthusiasm of the people just now.” Like Chase, Lincoln believed that the public, especially those who felt skittish about the election of a relatively unknown “western” politician, would welcome the chance to come out and see him in the flesh. He hoped that “when we shall become better acquainted,” as he would soon tell a group of fellow politicians, “we shall like each other the more.”

The initial announcement of Lincoln’s plans had claimed that the entire journey would be made “inside of ten days.” That optimistic prediction fell by the wayside as invitations to receptions and dinners along the route flowed into Springfield. Lincoln was eager to accept as many as possible, with the result that his itinerary expanded to include overnight stays in Pittsburgh and Cleveland, and numerous stops in smaller towns along the way. Each new invitation that Lincoln accepted added a fresh layer of complication to the planning. By the time the arrangements were settled, Lincoln’s intended route would crisscross over two thousand miles on eighteen different railroad lines, occasionally looping back on itself, as opposed to a journey of roughly seven hundred miles as the crow flies.

Lincoln himself acknowledged that this “rather circuitous route” left much to be desired. Mindful of time constraints, he urged one supporter to schedule “no ceremonies that will waste time,” and in some instances he promised only to “bow to the friends” at a particular stop if circumstances permitted. “Will not this roundabout way involve too much fatigue and exhaustion?” asked Salmon Chase, but Lincoln pressed ahead regardless. In the end, he would deliver more than a hundred speeches, sometimes at a clip of more than a dozen in a single day.

The unenviable job of adapting Lincoln’s ballooning agenda to the realities of railroad travel fell to Superintendent of Arrangements William S. Wood. A suave, silver-haired New York railroad man, Wood surfaced in Springfield after the election and offered to coordinate the irksome details of Lincoln’s journey, perhaps hoping to be rewarded with a patronage job in Washington. Wood undertook the thankless task with uncommon zeal. He promptly embarked on a scouting trip across the disjointed network of rail lines that connected Springfield to Washington, crafting a route that would allow Lincoln to make his desired “stoppages” while keeping the train to a tight, sometimes grueling schedule. At the same time, Wood made arrangements for the special trains and carriages that would be necessary at each phase of the journey, and negotiated with hotels in each city to ensure the “comfort and safety” of the presidential party.

At a time when hundreds of powerful men were jostling for position at Lincoln’s elbow, Wood’s duties required enormous tact and diplomacy, two qualities that were conspicuously absent in his overbearing, “relentlessly executive” nature. According to Henry Villard, Wood was “greatly impressed with the importance of his mission and inclined to assume airs of consequence and condescension.” There would be many more snappish comments by the time the Lincoln Special got rolling, but it is probably closer to the truth to say that Wood simply carried out Lincoln’s private wishes. At a time when the president-elect was going to heroic extremes to make himself available to all callers, Wood took on the unpopular role of gatekeeper.

Some of Wood’s high-handed behavior reflected the growing concern for Lincoln’s safety. To anticipate potential dangers, Wood looked to the example of a recent cross-country tour of America made by Britain’s Prince of Wales. Many of the same safeguards, Wood realized, could be adapted for Lincoln’s journey. The presidential train, like the royal one, would be preceded by special “pilot engines,” running a short distance ahead to scout for obstructions or hidden hazards. Once the advance crew passed safely over a section of track, the switches governing that portion of the line would be “spiked and guarded” until the Lincoln Special swept through. Wood also consulted with the presidents of the various railroads along the route, receiving promises that Lincoln’s train would be entitled to the exclusive use of the road—“

all other trains,

” ordered one executive, “

must be kept out of the way.

”

In an additional nod to security concerns, Wood printed up a detailed, if rather autocratic, “Circular of Instructions,” laying down a set of guidelines for Lincoln’s fellow travelers as well as the officials receiving him in each of the host cities. “Gentlemen,” he wrote, “Being charged with the responsibility of the safe conduct of the president-elect and his suite to their destination, I deem it my duty, for special reasons which you will readily comprehend, to offer the following instructions.” As it happened, Wood’s recommendations had more to do with protocol than safety, with a heavy emphasis on the niggling details of carriage rides and private dining rooms and “contiguous” hotel rooms. Aware that he risked raising hackles along the route, Wood added a plea for unity: “Trusting, gentlemen, that inasmuch as we have a common purpose in this matter, the safety, comfort and convenience of the President elect, these suggestions will be received in the spirit in which they are offered.”

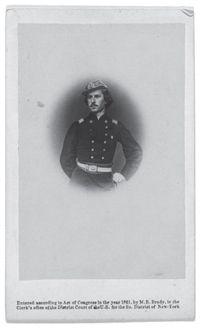

Amid all his fussing over seating charts, however, Wood made one pronouncement—possibly at Lincoln’s suggestion—that cut to the heart of safety concerns: He designated twenty-three-year-old Elmer Ellsworth as the point man for the president-elect’s security. It was an inspired decision. A dashing, Byronic figure, Ellsworth had captured the nation’s attention at the head of a flashy military drill team, the “U.S. Zouave Cadets,” who were rakishly attired in scarlet trousers and blue jackets with gold braiding, modeled on the uniforms of a celebrated French battalion that fought in the Crimean War. Ellsworth’s guardsmen traveled the country, whipping up patriotic fervor with their acrobatic parade-ground drills. As one admirer related, “They would fall to the ground, load their guns, fire, turn over on their backs, fire again, jump up, run a few steps, fall, then crawl on their hands and feet as silent and quick as cats, climb high stone walls by stepping on each other’s shoulders, making a human ladder.” Ellsworth, with his trim, compact build and dark good looks, soon achieved a sort of heartthrob status. “His pictures sold like wildfire in every city of the land,” noted

The Atlantic Monthly.

“Schoolgirls dreamed over the graceful wave of his curls.”

Ellsworth had come to Lincoln’s attention the previous year, when his unit staged an exhibition before an appreciative crowd in Springfield. “The predominance of crinoline was particularly notable,” observed the

Illinois State Register,

in a nod to Ellsworth’s many female devotees. The young officer also found an admirer in Lincoln, who stood and watched the spectacle for two hours in the shade of a cottonwood tree. Ellsworth had become an enthusiastic campaigner for Lincoln by that time, and the grateful candidate came to take a fatherly interest in his fortunes. Within a month of the Zouave exhibition, Ellsworth was back in Springfield, working as a clerk in the offices of Lincoln and Herndon. He soon became a frequent presence in the Lincoln home and “a great pet in the family,” according to one relation. Ellsworth had been at Lincoln’s side on Election Day, even escorting the candidate to the polling station, and his voice had been one of the loudest in cheering the result.

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the dashing young Zouave.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In private moments Ellsworth wrote long letters to his fiancée, Carrie Spafford, alternating between expressions of undying love and snippets of practical advice: “take PLENTY of EXERCISE, and AVOID TIGHT LACING.” Now and then Ellsworth would touch on the growing apprehension in Springfield over Lincoln’s safety. “People here are in a huge sweat about secession matters,” he wrote, adding that it was now a common belief “among the better informed” that some sort of attempt on Lincoln’s life “will surely be made.”

As the weeks passed, Ellsworth’s continued presence in Springfield gave rise to rumors that Lincoln would be escorted to Washington by a full complement of fifty Zouaves, resplendent in their scarlet-and-blue attire. This would have been exactly the type of saber rattling that Lincoln wished to avoid. Soon, a denial appeared in the

Herald.

“Mr. Lincoln,” readers were assured, “has too much common sense to entertain so ridiculous a scheme for a moment.”

If there was no room on the train for a corps of rifle-twirling cadets, however, a place was easily found for their charismatic leader. William Wood, in his role as superintendent of arrangements, saw at once that Ellsworth’s renown and his close ties to Lincoln could be turned to his own uses. The presence of the much-admired officer would signal that protective measures were in place, even if largely ceremonial in form. Lincoln, for his part, could scarcely object to the presence of a man who had become, as many friends would remark, “like a son” to him.

In his “Circular of Instructions” to the reception committees along the train’s route, Wood attempted to give shape to Ellsworth’s duties:

The President-elect will under

no circumstances

attempt to pass through any crowd until such arrangements are made as will meet the approval of Colonel Ellsworth, who is charged with the responsibility of all matters of this character, and to facilitate this, you will confer a favor by placing Col. Ellsworth in communication with the chief of your escort, immediately upon the arrival of the train.

Ellsworth would be the only member of the entourage with any official security designation, but in the days leading up to departure, several other military men would vie for seats on the train, with an eye toward protecting the president-elect. Capt. John Pope, like Ellsworth, managed to straddle the line between family circle and armed escort—the future general was a relation of Mrs. Lincoln’s. David Hunter, the army major who had written to advise the deployment of 100,000 Wide Awakes to Washington, received a cordial but unequivocal invitation from Lincoln himself: “I expect the pleasure of your company.” A friend of Hunter’s, Col. Edwin Vose Sumner, also intended to be on hand. “I have heard of threats against Mr. Lincoln,” Sumner declared, “and of bets being offered that he would never be inaugurated. I know very well that he is not a man to live in fear of assassination, but when the safety of the whole country depends upon his life, I would respectfully suggest to him whether it would not be well to give this matter some attention.” At sixty-four years of age, Sumner was nearly three times as old as Ellsworth, and believed himself to be the senior man in Lincoln’s security retinue.