The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (19 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

Lincoln also had a number of self-appointed bodyguards among his civilian friends, including two of his closest advisers: Norman Judd, an Illinois state senator whose imperious manner and thrusting white beard reminded some of a Russian czar, and Judge David Davis, a three-hundred-pound giant with “a big brain and a big heart” to match. Both men had had a hand in Lincoln’s election; Davis had managed the campaign, and Judd had been instrumental in bringing the Republican National Convention to Chicago. Both intended to see their man safely to Washington.

Far more vocal in his concern was Ward Hill Lamon, a gregarious, hard-drinking, banjo-playing companion of Lincoln’s days on the legal circuit. Like Judd and Davis, Lamon had been a major force in the presidential race, and he is generally credited with one of the more celebrated maneuvers of the Chicago convention—printing up duplicate tickets to ensure that the Wigwam would be packed with Lincoln supporters. In a memoir written many years later, Lamon recalled answering a summons to Springfield after the election. It was known that he had hopes of a diplomatic appointment in Paris, but, as Lamon reported it, Lincoln had other plans: “It looks as if we might have war,” Lincoln told him. “In that case I want you with me. In fact, I must have you. You must go, and go to stay.”

Lamon, no stranger to barroom brawling, seems to have believed that he would meet whatever dangers lay ahead with his fists and a scattering of concealed weapons. A physically commanding presence—over six feet tall and weighing nearly three hundred pounds—he arrived in Springfield carrying “a brace of fine pistols,” along with a set of brass knuckles, a large bowie knife, and a blackjack. “The fear that Mr. Lincoln would be assassinated,” Lamon recalled, “was shared by very many of his neighbors at Springfield,” and because of his long friendship with the president-elect, Lamon considered himself to be foremost in the chain of protectors. “No one knew Mr. Lincoln better,” he insisted, “none loved him more than I.” In later years, Lamon would often tell a story about being at Lincoln’s side as he prepared to depart for Gettysburg, where he would deliver his famous address at the scene of the pivotal battle. Upon being informed that he was in danger of missing his train, Lamon recalled, Lincoln offered a characteristic response: “Well, I feel about that as the convict did in Illinois, when he was going to the gallows. Passing along the road in custody of the sheriff, and seeing the people who were eager for the execution crowding and jostling one another past him, he at last called out, ‘Boys! You needn’t be in such a hurry to get ahead, for there won’t be any fun till I get there.’”

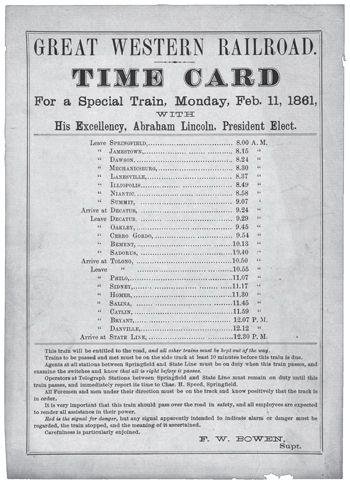

The anecdote underscored the central difficulty of planning Lincoln’s safe passage to Washington. In making the arrangements, William Wood had drawn up a detailed timetable for the journey and supplied copies to the press. The gesture was in keeping with Lincoln’s desire to make himself visible after the long winter in Springfield, but it also presented an enormous dilemma for the friends and advisers who wished to keep him safe. From the moment Lincoln’s train departed Springfield, anyone wishing to cause harm would be able to track his movements in unprecedented detail—even, at some stages of the journey, down to the minute. At a time when Lincoln was receiving daily threats of death by bullet, knife, poisoned ink, and spider-filled dumpling, the degree of precision in Wood’s timetable appeared to play into the hands of his enemies. So long as the trains ran on time, anyone intent on mischief would now have a window of opportunity calculated to the instant.

Of all the stops on Lincoln’s itinerary, only one would be made in a place where he had not actually been invited to appear. For the most part, as his secretary John Nicolay would attest, Lincoln’s movements had been planned at the invitation of various governors and state legislators. “No such call or greeting, however, had come from Maryland,” Nicolay observed, “no resolutions of welcome from her Legislature, no invitation from her Governor, no municipal committee from Baltimore.” Private citizens like Worthington Snethen, the resolute Wide Awake marcher, would make a few overtures. A Mr. R. B. Coleman, the manager of Baltimore’s Eutaw House hotel, went so far as to invite Lincoln to stay “for a week or more,” so as to give ample evidence that he was “not afraid to stop in a slave state.” Maryland’s elected officials, however, were conspicuous in their silence.

Capt. George Hazzard, a West Point graduate who had served with distinction in Mexico, was one of the first to apprehend danger behind that silence. Hazzard had been writing to Lincoln for some months with advice on matters ranging from election strategy to the strengthening of federal arsenals. When the itinerary for the inaugural journey became public, Hazzard turned his sights on Baltmore. “I hope the interest I feel in your personal safety and in the success of your administration will be a sufficient excuse for my addressing you this unsolicited communication,” he wrote. “I have the very highest respect for the integrity and abilities of your master of transportation, Mr. Wood, and did I not feel that

a residence of several years

in the city of Baltimore and four trips up and down the Potomac from its mouth to Washington City had given me some personal knowledge of the citizens and the geography of Maryland that Mr. Wood does not possess, I would not utter one word by way of advice or suggestion.”

Given the circumstances, however, Hazzard felt compelled to warn Lincoln about the likely perils of passing through Maryland, adding that “the greatest risk” would surely come in Baltimore, where there were many men who would “glory in being hanged” for having murdered an abolitionist president. Hazzard laid out three possible “courses of conduct” to meet the danger. The first, he suggested, would be to travel “openly and boldly” through the city, exactly as Lincoln planned to do at all the other stops on his route, but with the added security of a highly visible military escort. Clearly, Hazzard did not favor this plan. “It would take an army of 50,000 men and a week’s preparation to make a perfectly safe passage through a hostile city as large as Baltimore,” he believed. “Thousands of marksmen could fire from windows and housetops without the slightest danger to themselves.”

A moment-by-moment time card for the first day of Lincoln’s journey.

Courtesy of the Alfred Whital Stern Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

That being the case, Hazzard presented a second option: bypassing Baltimore entirely. The methods of doing so were limited at best, he explained, since the only viable alternate railroad route would pass into Virginia, a state that promised to be no less hostile than Maryland. To avoid both states, Lincoln might consider a voyage by steamboat from Philadelphia, making the final leg of the journey along the Potomac River, charting a middle course between the two unfriendly territories. The journey would be plagued by difficult navigation, Hazzard admitted: “In many places the scene is narrow and commanded by eminences from which an enemy could seriously annoy if not disable a single ship.” If Lincoln found himself compelled to go ashore, Hazzard warned, “the inhabitants would be very likely to detain you” until after the date of the inauguration had passed.

The third option, and the one that Hazzard appeared to favor, was a plan for catching Lincoln’s potential attackers off guard. Having studied the railroad routes and timetables carefully, Hazzard put forward a scenario that would allow the president-elect to deviate from his published timetable and pass through the city ahead of schedule. According to this plan, Lincoln would slip away from his entourage in Philadelphia or Harrisburg—“privately and unannounced with a very few friends”—and take a sleeper car through to Washington. If this could not be managed, Lincoln might stop outside of the city and board a different train, or perhaps even arrange for a horse and buggy to carry him the rest of the way to Washington. Any of these options, Hazzard explained, would allow the president-elect to avoid the point of greatest risk: riding in an open carriage from one depot to another in Baltimore, through a large and hostile crowd.

Not satisfied with a change of itinerary, Hazzard also suggested a change of appearance. He insisted that Lincoln should adopt a disguise for added security before showing himself on the streets of Baltimore. Apparently unaware that his correspondent had recently grown a beard, Hazzard suggested that a “false mustache” could be provided, along with “an old slouched hat and a long cloak or overcoat for concealment.” Even then, he maintained, Lincoln would have to be shadowed by a phalanx of guards walking “eight or ten paces” to the front and rear of him. If all of these precautions were adopted, Lincoln might be able to pass safely through the city. “This could be accomplished,” Hazzard concluded.

Significantly, all of Hazzard’s suggested “courses of conduct” rested on the assumption that Lincoln would come under fire in Baltimore. In weighing the risks, he compared Lincoln to an emperor at the gates of a conquered city, as opposed to the democratically elected president he was. Hazzard was clearly aware of the enormity of what he was proposing, and recognized that Lincoln had many reasons to resist any change of plan. “If after reading this communication you and your advisors shall think proper to go

openly

through Baltimore,” he concluded, “I shall feel fully satisfied that

all

the information in your possession justifies such a course and I will follow you to the last.” He closed with a final courtesy: “No answer is expected.”

Lincoln did reply, however. It is often supposed, given his later statements and his serene lack of concern at the time, that Lincoln was unaware of any stirrings of danger in Baltimore as he set forth from Springfield. In fact, the receipt of Hazzard’s letter made Lincoln aware of the looming trouble in January 1861—perhaps even before Allan Pinkerton caught wind of it. It is impossible to gauge how much credence Lincoln gave to Hazzard’s warning, but it is plain that he did not dismiss it out of hand. At a time when scores of politicians and office seekers were scrambling for passage on the inaugural train, Lincoln offered a seat to Hazzard. Like Ward Lamon, the young captain came prepared for whatever contingencies he might face. In his pockets he carried protective eyewear, brass knuckles, and a dagger. “In any event,” he told Lincoln, “I shall do myself the honor to witness your inauguration.”

CHAPTER TEN

HOSTILE ORGANIZATIONS

He soon became a welcome guest at the residences of many of the first families of that refined and aristocratic city. His romantic disposition and the ease of his manner captivated many of the susceptible hearts of the beautiful Baltimore belles, whose eyes grew brighter in his presence, and who listened enraptured to the poetic utterances which were whispered into their ears under the witching spell of music and moonlit nature.

—ALLAN PINKERTON on the efforts of Detective Harry Davies in Baltimore

DURING THE EARLY WEEKS

of February 1861, Pinkerton operative Harry Davies began spending a great deal of time in a Baltimore house of prostitution. The dimly lit wooden house at 70 Davis Street, in the shadow of the Calvert Street train station, had a narrow hallway at the front that opened onto a parlor filled with dark curtains, narrow divans, and gilt-framed paintings of wood nymphs and water sprites. Annette Travis, the proprietor, would greet her patrons with a warm smile and a glass of strong spirits. Behind her, two or three young women sat quietly on a painted bench, sometimes busying themselves with needlework. After a few pleasantries, the visitor was led to one of three upstairs chambers, where the business of the evening would be carried out.

It was not the sort of place one would expect to find Davies, the former seminarian. For more than a week, however, the detective had been working hard to cultivate the friendship of a young man named Otis K. Hillard, a sallow-faced, hard-drinking regular of the establishment. Hillard, according to Pinkerton, “was one of the fast ‘bloods’ of the city.” On his chest he wore a gold badge stamped with a palmetto, the symbol of South Carolina’s secession. It was known that Hillard had recently signed on as a lieutenant in the “Palmetto Guard,” one of several secret military organizations springing up in Baltimore.

Pinkerton had targeted Hillard, who came from a prominent family, as one of the Fire Eaters who regularly gathered at Barnum’s Hotel on Fayette Street, just off Monument Square. “The visitors from all portions of the South located at this house,” Pinkerton noted, “and in the evenings the corridors and parlors would be thronged by the tall, lank forms of the long-haired gentlemen who represented the aristocracy of the slaveholding interests. Their conversations were loud and unrestrained, and any one bold enough or sufficiently indiscreet to venture an opinion contrary to the righteousness of their cause, would soon find himself in an unenviable position and frequently the subject of violence.”