The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (28 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

At last, during a lull in the events at the rotunda, a telegram arrived bearing the Electoral College results from Washington: “The votes have been counted peaceably,” it read. “You are elected.” A small crowd of friends gathered around as Lincoln studied the message. “When he read it he smiled benignly,” wrote one witness, “and looking up, seeing everyone waiting for a word, he quietly put the dispatch in his pocket.” Pausing for a moment, Lincoln deflected his satisfaction into an innocuous comment about the new state capitol, as if to suggest that the outcome had never been in doubt: “What a beautiful building you have here, Governor Dennison,” he said.

The news had a bracing effect on Lincoln, who appeared cheerful and relaxed the following day at a stop near Rochester, Pennsylvania, where a local “coal-heaver” proposed a friendly contest: “Abe, they say you are the tallest man in the United States, but I don’t believe you are any taller than I am.” Lincoln, peering down from the rear platform of the train, immediately took up the challenge. “Come up here,” he called, “and let us measure.” The miner pushed his way through the crowd and climbed aboard. At Lincoln’s direction, he spun around and the two men stood back-to-back. Colonel Ellsworth, the dashing young Zouave officer, was hovering nearby as the spectacle unfolded. Turning toward him, Lincoln asked for a verdict: “Which is taller?” It was an awkward moment for Ellsworth, who stood barely five feet tall. Unable to see the tops of the taller men’s heads from his vantage point, Ellsworth scrambled onto a guardrail for a better view, amid much laughter from the crowd. “I believe,” he called out, “they are exactly the same height.” The locals cheered this diplomatic solution as Lincoln pumped the miner’s hand.

It marked a bright spot in an otherwise gloomy and rain-soaked day. Henry Villard believed that Lincoln felt relief at the sight of the “perfect torrents” of rain that began falling that morning, as the foul weather promised to reduce the size of the “uncomfortable crowds as had pestered him” in the previous days. This proved to be a vain hope. “Immense multitudes” turned out to greet the Lincoln Special as it cut through eastern Ohio toward Pennsylvania, where Lincoln would make an overnight appearance in Pittsburgh. Making light of his crisscrossing route and rapid pace, Lincoln trotted out a joke that would become familiar over the course of the journey. “I understand that arrangements were made for something of a speech from me here,” he told a crowd in Newark, Ohio, when the train accidentally overshot its scheduled stop, “but it has gone so far that it has deprived me of addressing the many fair ladies assembled, while it has deprived them of observing my very interesting countenance.”

In Pittsburgh the following morning—Friday, February 15—some five thousand people gathered outside the stately Monongahela House hotel to see the newly elected president. Lincoln stepped out onto the balcony of his second-floor room, only to find that the grim weather had followed him from Ohio, transforming the crowd below into an “ocean of umbrellas.” Though he had prepared some remarks of local interest, Lincoln once again paused to address the secession crisis, attempting to recast some of his ill-received sentiments of the previous days. “Notwithstanding the troubles across the river,” he began, pointing a finger in a southerly direction, “there is really no crisis springing from anything in the Government itself. In plain words, there is really no crisis, except an

artificial

one. What is there now to warrant the condition of affairs presented by our friends ‘over the river’? Take even their own view of the questions involved, and there is nothing to justify the course which they are pursuing. I repeat it, then—

there is no crisis,

excepting such a one as may be gotten up at any time by turbulent men, aided by designing politicians. My advice, then, under such circumstances, is to keep cool. If the great American people will only keep their temper on both sides of the line, the troubles will come to an end.”

Once again, Lincoln’s effort to downplay the nation’s troubles fared poorly in the press. The

New York Herald

despaired over his suggestion that “the crisis was only imaginary” and went on to list the many challenges facing his administration, including the potential dissolution of the Union, an empty public treasury, and “a reign of terror existing over one-half of the country.” It was worrying, the

Herald

claimed, that the new president seemed to regard these conditions as “only a bagatelle, a mere squall which would soon blow over.”

At the Pittsburgh train depot, Lincoln stood in the rain “without any signs of impatience” to shake hands with admirers, even pausing to bestow a kiss on a child who was passed over the heads of the crowd. At this, Henry Villard reported, “three lassies also made their way to him and received the same salutation.” As members of Lincoln’s escort stepped forward to offer a similar greeting, they were “indignantly repulsed amidst the laughter of the spectators.” When the time came to board the train, however, Lincoln and his party found their way barred by a “solid mass of humanity.” Herded forward by local Republican James Negley, later a Union general, they managed with difficulty to thread their way through the crowd “one by one in Indian file.”

The Lincoln Special pulled out of Pittsburgh at 10:00

A.M.

, with Lincoln bowing and doffing his hat from the rear platform. Up to this stage of the journey, the train had made a reasonably direct progress toward Washington, veering to the north and south as necessary to stop at the major cities along the way, but always keeping to an easterly heading. Now, instead of cutting directly across Pennsylvania toward Harrisburg, the itinerary took a wild, looping swing to the north to allow for stops in New York—“the greatest, richest and most powerful of the states,” as John Hay noted. As if to emphasize the impracticality of this leg of the journey, the day began with the train backtracking across the previous day’s route, heading west into Ohio for an overnight stop in Cleveland.

The driving rain had turned to snow by the time the Lincoln Special reached Cleveland at 4:30 that afternoon, but “myriads of human beings” turned out nonetheless, their ranks swelled by several companies of firemen and soldiers. “The anxiety to greet Honest Old Abe was evidently intense,” noted Villard. Heedless of the swirling snow, Lincoln stood and bowed as usual as an open carriage conveyed him along Euclid Avenue to the Weddell House, the five-story “Palace of the Forest City.”

By now, it had become the established custom that Lincoln’s arrival would be marked by a speech from the balcony of his hotel room. In Cleveland, he took the opportunity to repeat the substance of what he had said in Pittsburgh. “I think that there is no occasion for any excitement,” he insisted. “It can’t be argued up, and it can’t be argued down. Let it alone, and it will go down of itself.” This last remark drew appreciative laughter from the crowd but a good deal of acid from the press. The lead column of the

Cleveland Plain Dealer

the next day featured an “Epitaph” for the Union: “Here lies a people, who, in attempting to liberate the negro, lost their own freedom.” As an exercise in public relations, designed to reassure the North and placate the South, Lincoln’s inaugural trip had hit its lowest point. Writing in his diary, Congressman Charles Francis Adams—the son of one president and the grandson of another—expressed a fear that Lincoln’s speeches were “rapidly reducing” the public’s confidence. “They betray a person unconscious of his own position as well as the nature of the contest around him,” Adams wrote. “Good natured, kindly, honest, but frivolous and uncertain.”

The following day—Saturday, February 16—began on a disturbing note. Soon after the Lincoln Special left Cleveland, word came that a man had been killed during preparations for yet another thirty-four-gun salute along the route. The travelers were greatly relieved when a subsequent report corrected the first, informing them that the unfortunate man had merely been injured. By this time, however, Lincoln had cause to be thoroughly disenchanted with ceremonial displays of artillery. The previous day, while lunching at a hotel in Alliance, Ohio, the percussion of a nearby cannon salute shattered a window in the dining room, showering Mrs. Lincoln with glass. She recovered her composure quickly but came away thoroughly shaken by the experience.

By early Saturday afternoon, the Lincoln Special had pushed through the upper reaches of Pennsylvania and arrived at “the porch of the Empire State,” in the remote northwesterly village of Westfield, New York. “It was like entering St. Peter’s through a trap door,” wrote Hay. As it happened, Westfield was the home of Grace Bedell, the eleven-year-old girl who had written to advise Lincoln to grow his “whiskers” as a means of improving his appearance. “Some three months ago, I received a letter from a young lady here,” he declared from the rear of the train. “It was a very pretty letter, and she advised me to let my whiskers grow, as it would improve my personal appearance. Acting partly upon her suggestion, I have done so; and now, if she is here, I would like to see her.” Lincoln was immediately pointed in the direction of a girl who stood “blushing all over her fair face.” He climbed down from the platform and bent low to give her “several hearty kisses,” amid cheers from the crowd. “You see,” he told her, “I let these whiskers grow for you, Grace.”

As it happened, there was another celebrated set of whiskers to be seen aboard the Lincoln Special that day. Horace Greeley, whose “absurd fringe of beard” was the delight of editorial cartoonists, had come aboard earlier that morning at Girard, Pennsylvania. Though his arrival was unexpected, the famous editor of the

New-York Tribune

would have been hard to miss. He wore his trademark white coat—“that mysteriously durable garment,” as Hay described it—and carried a bright yellow case that announced his name “in characters which might be read across Lake Erie.”

The influence of Greeley and his pro-Republican

Tribune

was unparalleled. The previous year, his opposition to William Seward had helped to tip the presidential nomination to Lincoln. Accordingly, the editor’s sudden appearance aboard the Lincoln Special created “no little sensation,” according to Villard. “He was at once conducted into the car of the President-elect, who came forward to greet him.” After conferring privately with Lincoln, Greeley hopped off the train some twenty miles down the line to file an enthusiastic report: “His passage through the country has been like the return of grateful sunshine after a stormy winter day. The people breathe more freely and hope revives in all hearts.” Greeley had grave concerns, however, about Lincoln’s safety. A few days later, he would report that “substantial cash rewards” were on offer in the Southern states to anyone who succeeded in murdering the president-elect before the inauguration. Lincoln, he believed, was “in peril of outrage, indignity, and death.”

* * *

AS THE LINCOLN SPECIAL PRESSED

on toward Buffalo on Saturday afternoon, Allan Pinkerton’s investigation in Baltimore was also gaining on speed. Even as Lincoln said farewell to young Grace Bedell, Pinkerton was again mingling among the patrons at Barnum’s Hotel, hoping to pick up the trail of Cypriano Ferrandini, the self-professed revolutionary who had sworn that Lincoln would not live to become president. Pinkerton’s earlier meeting with Ferrandini had been interrupted before the detective could extract any details of Ferrandini’s “fully arranged” plan. Now, Pinkerton hoped to uncover the facts he would need to thwart the conspiracy.

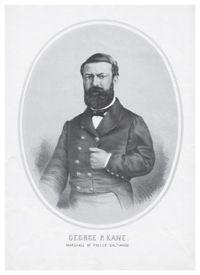

Though Ferrandini was nowhere to be seen that day, Pinkerton found himself unexpectedly presented with a chance to take the measure of one of Baltimore’s most-talked-about citizens. George P. Kane, a resolute-looking man with a dark beard and military bearing, was holding court at Barnum’s with a group of drinking companions. As the newly appointed marshal of Baltimore’s police force, Kane would play a central role in Lincoln’s passage through the city, and Pinkerton was anxious to know if he could be trusted.

Baltimore’s police marshal George P. Kane, whose loyalties Pinkerton doubted.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Marshal Kane had become a key figure in Baltimore’s effort to erase its “Mobtown” image. The previous year, a reform committee within the state legislature had enacted a bill to address the city’s “unchecked ruffianism,” and it had selected Kane to lead a newly revitalized police force. Kane was known to be a man of strong convictions as well as great personal courage. Years earlier, while on duty in Annapolis with his state militia unit, Kane had been called to the City Dock when fighting broke out between local townsmen and a group of “incorrigibles” aboard a Baltimore ship. Stones and bricks were thrown, and the matter soon escalated to the point where cannons were being readied to fire upon the ship. Kane and a pair of fellow officers coolly stepped forward and placed themselves at the mouths of the cannon to prevent the townsmen from firing. This display of unflinching bravery quieted the mob and defused the crisis.