The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (31 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

By any measure, this was an astonishingly reckless exchange on the part of both men. In effect, Davies had goaded Hillard into making a vow to assassinate the president-elect. It is difficult to gauge, based on the dry and uninflected language of Davies’s field report, the degree to which either man was in earnest. As the two continued talking, however, it became evident that Hillard had no intention of carrying out the deed alone and unabetted, but Davies’s offer appeared to have strengthened his determination to assist in Ferrandini’s designs, if so ordered. As he turned the matter over in his mind, Hillard’s enthusiasm grew. The money Davies had pledged would be of no use to him personally, he explained, but that was of no concern. “Five hundred dollars would help my mother,” he said, “because I would expect to die, and I would say so soon as it was done: ‘Here gentlemen take me, I am the man who [has] done the deed.’”

Hillard returned to the subject several times over the course of the day. By evening, Davies’s bold statement had inspired further confidences. As the two men dined together at Mann’s Restaurant, Hillard at last confirmed that his unit of the National Volunteers might soon “draw lots to see who would kill Lincoln.” If the responsibility fell upon him, Hillard boasted, “I would do it willingly.”

Davies was keenly aware that he had reached an important crossroads, as Hillard had never before spoken so openly. After offering assurances that he had no wish to pry, Davies gingerly admitted to a natural curiosity—“being a Southern man”—as to the true extent of the plans Hillard had mentioned.

Hillard hesitated. “I have told you all I have a right to tell you,” he said at last. “Do not think, my friend, that it is a want of confidence in you that makes me so cautious. It is because I have to be.” The reason for this was simple, Hillard explained as he glanced about the restaurant: There were “government spies here all the time.” As evidence of this, he mentioned his summons to testify before the select committee two weeks earlier. Hillard could not recall having spoken of the National Volunteers to anyone outside of the organization, but nevertheless he had been called to Washington to give evidence. To his mind, this was proof of spies in their midst. That being the case, the Volunteers had to be on their guard at all times. “We have taken a solemn oath,” he explained, “which is to obey the orders of our Captain, without asking any questions, and in no case, or under any circumstances, reveal … anything that is confidential.” Hillard was careful not to mention the names of Ferrandini or any other member of the secret order, not realizing that Davies and Pinkerton had already identified the key figures.

Davies continued to press. “It is none of my business to ask you questions about your Company,” he admitted, but he wondered if perhaps the young lieutenant could go so far as to reveal “the first object” of the organization. Hillard weighed the question for a moment. “It was first organized to prevent the passage of Lincoln with the troops through Baltimore,” he said after a time, “but our plans are changed every day, as matters change. What its object will be from day to day I do not know, nor can I tell. All we have to do is to obey the orders of our Captain—whatever he commands we are required to do.” Hillard took a significant pause, apparently wrestling with a desire to confide something further, but after a moment’s struggle he restrained himself. “Rest assured I have all confidence in you,” he said, but “I cannot come out and tell you all. I cannot compromise my honor.”

* * *

AS HILLARD RETREATED ONCE AGAIN

behind his oath to the National Volunteers, Davies fell into despair. On Pinkerton’s orders, Davies had pushed as far as he dared, even pledging money to a potential assassin in his urgent pursuit of information. Pinkerton, who had passed over twenty-five dollars to James Luckett a few days earlier, clearly believed that such measures were an accepted component of undercover work, and a necessary concession to the limited time in which he had to work. For the moment, however, the aggressive tactics appeared to have failed. The surviving portion of Davies’s field report ends with Hillard’s refusal to compromise his “solemn oath.” According to Pinkerton’s recollections, however, the situation soon took a more favorable turn. On hearing what had transpired, Pinkerton saw that Hillard’s revelation about the ballot drawing had provided them with a tool to overcome the young lieutenant’s intransigence. In an account published many years later, Pinkerton claimed that he instructed Davies to demand to be taken to this fateful meeting, insisting that he, too, wished to be given the “opportunity to immortalize himself” by murdering Abraham Lincoln. “Accordingly,” Pinkerton wrote, “that day Davies broached the matter to Hillard in a manner which convinced him of his earnestness, and the young Lieutenant promised his utmost efforts to secure his admission.” Hillard then withdrew, apparently to plead his friend’s case to Ferrandini. Soon, Hillard returned in exuberant spirits. If Davies would be willing to swear an oath of loyalty, he could join Ferrandini’s band of “Southern patriots” that very night.

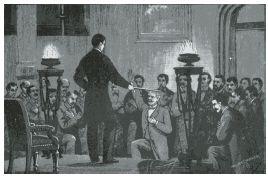

As evening fell, Pinkerton’s account continues, Hillard conducted Davies to the home of a man who was well known among the secessionists. The pair were ushered into a large drawing room on the ground floor, where a group of twenty men stood waiting. “The members were strangely silent,” Pinkerton declared, “and an ominous awe seemed to pervade the entire assembly.” At last, Davies found himself being led forward to meet their “noble Captain,” as Hillard repeatedly called him, whose identity had been so closely guarded. As Pinkerton and Davies had expected, this proved to be Cypriano Ferrandini, who had dressed for the occasion in funereal black from head to toe. Ferrandini greeted Davies with a crisp nod, but no words passed between them. As Pinkerton had noted earlier at Barr’s Saloon, the others treated their solemn-faced leader with marked deference. Each new man who entered crossed the room to pay his respects, and sought his approval before speaking.

Pinkerton operative Harry Davies takes his oath as a member of Ferrandini’s band.

At a signal from Ferrandini, heavy curtains were drawn tight across the windows. In the flickering light of candles, the “rebel spirits” formed a circle as Ferrandini instructed Davies to raise his hand and swear allegiance to the cause of Southern freedom. “Having passed through the required formula,” Pinkerton wrote, “Davies was warmly taken by the hand by his associates, many of whom he had met in the polite circles of society.” With the initiation completed, Ferrandini proceeded to the main business of the evening. Climbing onto a chair, he explained in hushed tones that he had assembled this sacred trust of patriots to ensure the preservation of the Southern way of life. Ferrandini’s voice gathered force as he spoke, and he carefully reviewed each step of the plan to divert the police at the Calvert Street Station, allowing their chosen assassin to strike. After elaborating on the design, he reminded his followers of the importance of their mission. “He violently assailed the enemies of the South,” as Davies reported to Pinkerton, “and in glowing words pointed out the glory that awaited the man who proved himself the hero upon this great occasion.” Davies noted that all present appeared to draw courage and resolve from Ferrandini’s words. Beside him, Hillard stood with a straight back and steadfast expression, as if his earlier fears were now forgotten. As Ferrandini brought his remarks to a “fiery crescendo,” he drew a long, curved blade from beneath his coat and brandished it high above his head. “Gentlemen,” he cried to roars of approval, “this hireling Lincoln shall never, never be President!”

When the cheers subsided, Ferrandini turned at last to the selection of Lincoln’s killer. “For this purpose the meeting had been called,” as Davies well knew, “and tonight the important decision was to be reached.” A wave of apprehension passed through the room. “Who should do the deed?” Ferrandini asked his followers. “Who should assume the task of liberating the nation of the foul presence of the abolitionist leader?”

Ferrandini explained that a number of paper ballots had been placed into the heavy wooden chest that sat on the table in front of him. One of these ballots, he continued, was marked in red to designate the assassin. “In order that none should know who drew the fatal ballot, except he who did so, the room was rendered still darker,” Davies reported, “and everyone was pledged to secrecy as to the color of the ballot he drew.” In this manner, Ferrandini told his followers, the identity of the “honored patriot” would be protected until the last-possible instant.

One by one, the “solemn guardians of the South” filed past the wooden box and withdrew a folded ballot slip. As each man passed, Ferrandini smiled approvingly and murmured a few words of encouragement. Ferrandini himself took the final ballot and held it high in the air, telling the assembly in a hushed but steely tone that their business had now come to a close. There should be no further discussion of the matter until the very moment of Lincoln’s arrival, he reminded them, to ensure that nothing should happen to compromise their plan. With a final word of praise for the strength and conviction of their “Southern ideals,” Ferrandini brought the meeting to a close.

Hillard and Davies walked out into the darkened streets together, after first withdrawing to a private corner to open their folded ballots. Davies’s own ballot paper was blank, a fact he conveyed to Hillard with an expression of ill-concealed disappointment. As they set off in search of a stiffening drink, Davies pretended to feel anxiety as to whether the plan could succeed. He told Hillard that he admired the strategy but was worried that the man who had been chosen to carry it out—whoever he might be—would lose his nerve at the crucial moment. Hillard waved the objection aside. Ferrandini had anticipated this possibility, he said, and had confided to him that a safeguard was in place to prevent such a failure. The wooden box, Hillard explained, had contained not one red ballot, but eight, and all eight were now in the hands of Ferrandini’s men. Each man would believe wholeheartedly that he alone was charged with the task of murdering Lincoln, and that the cause of the South rested solely upon “his courage, strength and devotion.” In this way, even if one or two of the chosen assassins should fail to act, at least one of the others would be certain to strike the fatal blow. For Hillard’s benefit, Davies feigned relief over the ingenuity of Ferrandini’s deception. Soon, after reviewing the events of the evening over a glass of whiskey, Davies found an excuse to withdraw for the evening.

Moments later, Davies was hurrying along the back alley behind Pinkerton’s South Street building, with the collar of his overcoat drawn tight around his face. He clambered up the rear stairs and burst into the office, launching into his account of the evening’s events even before the door had closed behind him. Pinkerton sat at his desk, furiously scribbling notes as Davies spoke, breaking in every so often to ask a question or confirm a detail.

When Davies had finished, Pinkerton sat back in his chair and pondered his next move. He found himself forced to admit to a grudging admiration for the murderous plot as Ferrandini had outlined it. “It was a capital one,” he acknowledged, and it would require his best effort if it were to be averted. It was now clear that the period of “unceasing shadow,” as he had described his operations in Baltimore, had come to an end.

“My time for action,” he later declared, “had now arrived.”

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

WHITEWASH

For the benefit of laymen I will state that in a crowd as great as the greatest, you can always be sure of getting through it if you follow these instructions: Elevate your elbow high, and bring it down with great force upon the digestive apparatus of your neighbor. He will double up and yell, causing the gentlemen in front of you to turn halfway round to see what is the matter. Punch him in the same way, step on his foot, pass him, and continue the application until you have reached the desired point. It never fails.

—JOSEPH HOWARD of the

New York Times,

from aboard the Lincoln Special

KATE WARNE, IN THE PERSON

of Mrs. Barley of Alabama, had become a familiar sight in the hotel parlors and tearooms of Baltimore by this time. The young widow invariably found a seat at the edge of a large group of women and busied herself with a book or a piece of needlework, nodding pleasantly as she settled herself. With the dangling black and white ribbons of a Southern cockade pinned to her breast, Mrs. Warne, whose kindly blue eyes seemed to resonate with the laughter and animated comments nearby, would allow herself by slow degrees to be drawn into the neighboring conversations. She had “an ease of manner that was quite captivating,” Pinkerton observed, “and had already made remarkable progress in cultivating the acquaintance of the wives and daughters of the conspirators.”

As a rule, Pinkerton’s operatives avoided one another in public, so as reduce the risk of exposure if suspicion fell on a particular detective. It came as a surprise, therefore, when Pinkerton himself appeared suddenly in the parlor of Mrs. Warne’s hotel on the morning of February 18, signaling an urgent need to speak in private. Taking leave of her latest group of new friends, Mrs. Warne rose and quietly made her way to her room. Moments later, Pinkerton followed, unobserved.