The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (46 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

Downstairs in the lobby of Willard’s Hotel, Seward soon reappeared to collect Lincoln, who was now refreshed after a short nap. Together, they began making the rounds of official Washington in the hope, as one congressman would remark, that the new president might “break through the prejudices created by the manner of his entry into the capital.” Lincoln’s first stop was an unannounced call at the White House, where outgoing President James Buchanan interrupted a cabinet meeting to greet his successor in “a very cordial manner.” Buchanan led a brief tour of the premises, and he seemed especially pleased to hear that Lincoln had received “a satisfactory reception at Harrisburg,” near Buchanan’s Wheatland estate. Though friendly in tone, the surprise visit sent a strong message that Lincoln was ready to serve—“a

coup d’état,

” declared the

New York Herald.

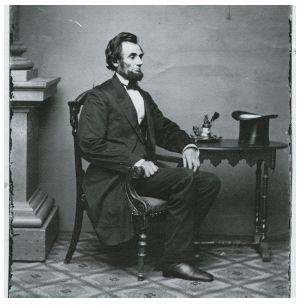

Lincoln at Mathew Brady’s studio in Washington on February 24, 1861, the day after his passage through Baltimore.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

From the White House, Lincoln attempted to pay his respects at the headquarters of Winfield Scott, who had shared so fully in the concern for his safety. The general was not there to receive him, but he soon returned the call at Willard’s Hotel, resplendent in his full dress uniform, including plumed hat and ceremonial sword. In spite of his advanced age and recent illness, General Scott made a point of greeting his new commander in chief with a deep, formal bow. “It would do the drawing room dudes of today good,” wrote one observer, “to have witnessed the profound grace of the old hero’s acknowledgment of the presence of the President-elect, as he swept his instep with the golden plumes of his chapeau.” Like Seward, the general appeared keen to cast the best-possible light on Lincoln’s decision to bypass Baltimore. “General Scott expressed his great gratification at Mr. Lincoln’s safe arrival,” reported the

Herald,

“and especially complimented him for choosing to travel from Harrisburg unattended by any display, but in a plain democratic way.”

The notion that Lincoln had traveled as he did to avoid ostentation was easily the most peculiar of the many explanations advanced that day. Be that as it may, General Scott’s public show of support was crucial, and it gave credence to newspaper reports that he, America’s most revered military hero, had personally insisted that Lincoln avoid Baltimore. “Mr. Lincoln is in no way responsible for the change of route in coming to this city,” ran one account. “He acted under official communication from General Scott.” In addition, the press reported, the old soldier would remain vigilant throughout the inauguration, so that “no slip up, no stiletto, no revolver, no desperado can prevent the peaceful and actual installing of the man whom the people honor, in the place which Providence has ordained him to fill.”

* * *

THOUGH WILLIAM SEWARD

would be at Lincoln’s elbow for most of the day, the future secretary of state detached himself for a few moments that afternoon to return to the train station and collect Mrs. Lincoln and her sons. The safety of his family had weighed heavily on Lincoln’s mind throughout the night, and he had sent a telegram to Harrisburg that morning to reassure Mary of his own safe arrival. Even so, it would not escape the notice of the Southern press that Lincoln had consigned his family “to follow him in the very train in which he himself was to be blown up.” The

Baltimore Sun

was especially outspoken on the subject, praising Mrs. Lincoln’s sturdy resolve at the expense of her husband’s timidity. The future first lady had “warmly opposed” the change of plan, the

Sun

reported, and determined “to disprove the whole story” by carrying out her husband’s itinerary in his absence. “So there is to be some pluck in the White House,” the account concluded, “if it is under a bodice.”

In fact, the reports of how Mrs. Lincoln and her sons passed through Baltimore are garbled and contradictory. By some accounts, Lincoln was advised that the simple fact of his absence from the train would protect his family from harm, with no further precautions needed. Others have suggested that he would not have left Harrisburg unless a plan had been set in motion for his family’s safety. What is clear is that Mrs. Lincoln, her sons, and the remaining members of the suite departed from Harrisburg as scheduled at nine o’clock that morning, amid a climate of deep apprehension. Norman Judd would later tell Pinkerton that there had been “some very tall swearing” among the travelers who were not in on the secret. “All the party are on the train, though but few think we shall reach Washington without accidents,” wrote one correspondent. “Colonel Ellsworth expects the train will be mobbed at Baltimore.” Many on board were outraged by Lincoln’s early departure, it was reported: “They call it cowardly, and draw a parallel between the conduct of Mr. Lincoln and the actions of the South Carolinians, very much to the disadvantage of the former.” Robert Lincoln, at least, stood fast behind his father. A little before noon, as the train crossed into Maryland, he led his fellow passengers in a spirited rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Upon arrival in Baltimore, Pinkerton would relate, the travelers “met with anything but a cordial reception.” Joseph Howard, apparently recovered from his brief incarceration the previous evening, gave a chilling account in the

Times.

“It was well that Mr. Lincoln went as he did—there is no doubt about it,” he declared. “The scene that occurred when the car containing Mrs. Lincoln and her family reached the Baltimore depot showed plainly what undoubtedly would have happened had Mr. Lincoln been of the party. A vast crowd—a multitude, in fact—had gathered in and about the premises. It was evident that they considered the announcement of Mr. Lincoln’s presence in Washington a mere ruse, for thrusting their heads in at the windows, they shouted ‘Trot him out,’ ‘Let’s have him, ‘Come out, old Abe,’ ‘We’ll give you hell’—and other equally polite but more profane ejaculations.” A number of these “rude fellows” succeeded in forcing their way into Mrs. Lincoln’s carriage, Howard continued, but John Hay managed to push them out and lock the door behind them. Meanwhile, the unseemly display on the platform continued: “Oaths, obscenity, disgusting epithets and unpleasant gesticulations were the order of the day.”

For all its colorful detail, Howard’s account may well have been a complete fabrication, part of the reporter’s effort to demonstrate the wisdom of Lincoln’s decision. Howard’s story is directly contradicted by several sources that claimed Mrs. Lincoln was not on board the special when it arrived at the Calvert Street Station that day. The

Philadelphia Inquirer

was one of several newspapers to report that “the family of Mr. Lincoln left the train” at a track crossing at Charles Street, about a mile short of the station, to be spared any unpleasantness at the hands of the crowd. The story was given out that Mrs. Lincoln had accepted an invitation to lunch at the home of Col. John S. Gittings, the president of the Northern Central Railroad, to demonstrate that “no ill-feeling or suspicion towards him” had inspired her husband’s change of plan. It was said that the family alighted at the city limits, along with Judge Davis and Colonel Sumner, and “took carriages that had been in readiness” to the Gittings mansion, located in the fashionable Mount Vernon district north of town. The remaining travelers, meanwhile, continued on to Calvert Street, then proceeded from there to a reception at the Eutaw House hotel, as previously announced in the press. In this version of events, Mrs. Lincoln was said to have rejoined the travelers later in the day to continue the journey from Camden Street.

If the details are murky, the role of Baltimore’s marshal of police, George P. Kane, is nearly opaque. In the coming days, Kane would be accused of complicity in both extremes of the Baltimore plot: some would accuse him of active collusion with the conspirators, while others would claim that he engineered the change of plan for both the president-elect and his wife. Kane’s own testimony did little to illuminate the matter. The day after Lincoln’s arrival in Washington, he would issue a forceful statement, denying that any serious threat had been discovered. “It was thought possible that an offensive Republican display, said to have been contemplated by some of our citizens at the railroad station, might have provoked disorder,” he admitted, but “ample measures were accordingly taken to prevent any disturbance of the peace.” Elsewhere, Kane would deny any role in Lincoln’s decision to alter his itinerary: “I did not recommend that the President-elect should avoid passing openly through Baltimore, nor did I, for one moment, contemplate such a contingency.”

Later, when a

Harper’s Weekly

article suggested that he had conspired against Lincoln, Kane wrote an angry response, elaborating on his role in the events. Kane now claimed not only that he had arranged for Mrs. Lincoln’s reception at the home of Colonel Gittings but that he had intended for Lincoln himself to follow the same course, departing the train at the city limits. Kane had grown concerned, he said, that Lincoln would be annoyed by the “noise and confusion” at the depot, along with “candidates for office, and fanatics on the negro question.” That being the case, he suggested to Colonel Gittings that “it would be a fit and graceful thing for him to meet Mr. Lincoln at the Maryland line, and invite him and his family to become his guests during their stay in Baltimore.” In this telling of the events, Kane made it clear that he himself planned to escort Lincoln and his family to Mount Vernon Place. Even now, however, he maintained that the “intended debarkation” had nothing whatever to do with “apprehension or suspicion of intended violence or insult to Mr. Lincoln.” To the contrary, he simply wished to show the city to its best advantage, and believed that the change of route afforded a view of “the most beautiful part of Baltimore.”

Kane’s statements must be treated with caution, as they encompass a fair number of evasions and inconsistencies. If the marshal had truly intended to give Lincoln a fitting reception, it seems curious that he did not inform Baltimore’s mayor, George Brown, who was left waiting at Calvert Street that day, intending “to receive with due respect the incoming President.” By some accounts, Kane himself was also at the station when the Lincoln Special arrived, directing the actions of a robust police presence. In spite of all the contradictions, there is strong evidence to suggest that Mrs. Lincoln did, in fact, accept Colonel Gittings’s hospitality as a means of avoiding the scene at Calvert Street. Lincoln himself is said to have extended his thanks to Mrs. Gittings at a later meeting: “Madam, I owe you a debt. You took my family into your home in the midst of a hostile mob. You gave them succor, and helped them on their way.”

If the story is true, and if Marshal Kane had a hand in the maneuver, it would perhaps place a different construction on Kane’s actions in the days prior to the arrival. Pinkerton would dismiss Kane as a “rabid rebel,” and was convinced that he would “detail but a small police force” as the conspirators did their sinister work at Calvert Street. The detective had been especially alarmed at the remark he overheard at Barnum’s hotel, as Kane apparently told companions that he saw no need to provide a police escort during Lincoln’s visit to the city. Pinkerton construed the remark as a sign of Kane’s indifference to Lincoln’s safety, or perhaps even his active participation in the plot. If, however, Kane had already hatched a design for removing Lincoln from the train, his attitude may be read as the confidence of a man who had already taken preventative measures. The wisdom of such a course would have been debatable at best, as violence would likely have erupted in any case, but there is reason to think that Kane would not have been greatly troubled if a brawl broke out at the station in these circumstances. He had already branded the probable victims—Lincoln’s Republican supporters—as the “very scum of the city.”

* * *

BACK IN WASHINGTON,

Pinkerton reported Lincoln’s safe arrival to Samuel Felton and others in a series of laconic telegrams. One of these, to Edward Sanford of the American Telegraph Company, declared:

“Plums arrived here with Nuts this morning—all right.”

Ward Lamon would later grouse that Lincoln had been “reduced to the undignified title of ‘Nuts’” in these messages, but as several of the recipients did not have the cipher key, most of Pinkerton’s dispatches were sent in the clear. The telegram to Norman Judd, for instance, read simply “Arrived here all right.”

Pinkerton remained convinced that the plotters in Baltimore still posed a threat, and he now made preparations to return to the city on the three o’clock train to resume his work as “John H. Hutchinson.” So far as the detective was concerned, he was still on the job, and still operating under cover. Lincoln’s safe passage, in Pinkerton’s view, had been only one battle of a larger campaign. He knew full well that details of Lincoln’s arrival were already appearing in newspapers across the country, but he still believed that his role in the matter must remain secret, especially while he and his agents remained at risk in Baltimore.