The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (48 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

* * *

SOON AFTER THE BOMBARDMENT

of Fort Sumter, in April, Timothy Webster arrived in Washington carrying several important dispatches—carefully sewn into his clothing by Kate Warne—for hand delivery to President Lincoln. One of these was a letter from Pinkerton:

Dear Sir

When I saw you last I said that if the time should ever come that I could be of service to you I was ready—If that time has come I am on hand—

I have in my Force from Sixteen to Eighteen persons on whose courage, skill & devotion to their country I can rely. If they with myself at the head can be of service in the way of obtaining information of the movements of the traitors, or safely conveying your letters or dispatches, or that class of Secret Service which is the most dangerous, I am at your command.

In the present disturbed state of affairs I dare not trust this to the mail—so send by one of my force who was with me at Baltimore—You may safely trust him with any message for me—written or verbal—I fully guarantee his fidelity—He will act as you direct—and return here with your answer.

Secrecy is the great lever I propose to operate with—Hence the necessity of this movement (If you contemplate it) being kept

Strictly Private

, and that should you desire another interview with the Bearer that you should so arrange it as that he will not be noticed—The Bearer will hand you a copy of a Telegraphic Cipher which you may use if you desire to Telegraph me—

My Force comprises both Sexes—all of good character—and well skilled in their business—

Respectfully yours

Allan Pinkerton

At Lincoln’s request, Webster returned the following morning to collect Lincoln’s reply, which requested that Pinkerton make his way to Washington at once. Taking his leave of the president, Webster rolled the message into a tight cylinder and concealed it in a hollow compartment of his walking stick.

The case files marked “Operations in Baltimore” were now closed and filed away. A new operation had begun.

EPILOGUE

AN INFAMOUS LIE

He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.…

He is a great observer and he looks / Quite through the deeds of men …

Such men as he be never at heart’s ease / Whiles they behold a greater than themselves, / And therefore are they very dangerous.

—JULIUS CAESAR

FOR SEVERAL WEEKS IN MAY 1861,

an enormous “Stars and Bars” could be seen clearly from the windows of the White House. The newly adopted flag of the Confederacy had been raised above the Marshall House hotel, directly across the Potomac River in Alexandria, Virginia. Though Virginia was still technically a state of the Union, with a vote on secession scheduled for May 23, the Confederate banner gave a clear indication of which way the wind was blowing. Newspapers carried reports of rebel troops massing in Alexandria and warned that an attack on Washington was imminent.

“The Flight of Abraham,” as depicted in

Harper’s Weekly.

For Col. Elmer Ellsworth, a regular visitor to the Lincoln White House, the sight of the rebel flag was a particularly bitter affront. In the days following the inauguration, Ellsworth had been sidelined with a case of measles contracted from Tad and Willie Lincoln, who so often had been under his care during the long journey from Springfield. On recovery, as the new president issued a proclamation calling up 75,000 militiamen, Ellsworth was eager to get into the fight. With Lincoln’s help, he secured a commission and raised a regiment of battle-ready volunteers from among the “turbulent spirits” of the New York City Fire Department. “They are sleeping on a volcano in Washington,” Ellsworth told a reporter, “and I want men who can go into a fight.”

On the evening of May 23, as Virginia’s secession became official, Ellsworth pulled strings to ensure that his “Fire Zouaves” would have the honor of being the first to march upon the Old Dominion state. Plans were laid to secure Alexandria the following morning. At midnight, alone in his tent on the banks of the Potomac, Ellsworth poured his feelings into a heartfelt letter to his fiancée:

My own darling Kitty,

My regiment is ordered to cross the river & move on Alexandria within six hours. We may meet with a warm reception & my darling among so many careless fellows one is somewhat likely to be hit.

If anything should happen—Darling just accept this assurance, the only thing I can leave you—the highest happiness I looked for on earth was a union with you.… I love you with all the ardor I am capable of.… God bless you, as you deserve and grant you a happy & useful life & us a union hereafter.

Truly your own,

Elmer

At dawn, federal troop steamers ferried Ellsworth and his men across the Potomac toward Virginia. On his chest, the “gallant little Colonel” wore a gold medal inscribed with the Latin phrase

Non nobis, sed pro patria

, meaning “Not for ourselves, but for country.” Setting down at an Alexandria wharf, Ellsworth’s regiment met no resistance. A thin line of Virginia militiamen had pulled back an hour earlier. Advancing quickly, Ellsworth dispatched a company of men to secure the train station while he led a separate column toward the telegraph office. Heading up King Street, in the center of town, Ellsworth passed the Marshall House and caught sight of the Confederate flag that had “long swung insolently” in full view of the White House. “Boys,” he said, “we must have that down before we return.”

Ellsworth paused for a moment, torn between his objective of cutting the city’s telegraph wires and his desire to pull down the offending flag. With a sudden resolve, he turned toward the Marshall House. Posting three guards on the ground floor, Ellsworth dashed up the stairs with a small detachment of men, trailed by reporter Edward House of the

New-York Tribune.

Scrambling up an attic ladder onto the roof, Ellsworth cut down the rebel banner and began rolling it up to carry back across the river. With Corp. Francis E. Brownell in the lead, Ellsworth climbed back down the ladder, still absorbed in gathering the flag as he made his way to the stairs. Edward House followed close behind, laying a balancing hand on Ellsworth’s shoulder.

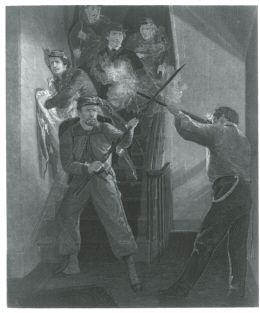

Suddenly, at the third-floor landing, a man leapt out from the shadows. James W. Jackson, the innkeeper, had sworn that the Stars and Bars would come down only over his dead body. Now, as he leveled a double-barreled shotgun, he intended to make good on the vow. Corporal Brownell batted at the weapon with his rifle, but Jackson pulled the trigger, firing one of its two barrels and striking Colonel Ellsworth square in the chest. “He seemed to fall almost from my grasp,” the reporter Edward House said. “He was on the second or third step from the landing, and he dropped forward with that heavy, horrible, headlong weight which always comes of sudden death.”

As Ellsworth fell, Jackson fired the second barrel, narrowly missing Corporal Brownell. At the same moment, the young soldier swung his rifle and returned fire. “The assassin staggered backward,” House wrote. “He was hit exactly in the middle of the face.” As Jackson crashed down the stairs, Brownell thrust his bayonet twice through the body.

“The sudden shock only for an instant paralyzed us,” one of the soldiers would recall. Recovering, they turned their attention to Ellsworth, who lay facedown at the bottom of the stairs, “his life’s blood perfectly saturating the secession flag.” His men carried him to a bedroom and ran water over his face, attempting to revive him, but to no avail. Unbuttoning his coat, they discovered that the blast had driven Ellsworth’s gold medal deep into his chest. “We saw that all hope must be resigned,” wrote House. Ellsworth was dead at the age of twenty-four, the first Union officer to fall in the line of duty.

The news reached the White House later that morning. Lincoln, who stared in anguish across the Potomac to the spot where the flag had flown, found himself unable to speak. By that time, church bells were tolling across the city and flags were being lowered to half-mast. An honor guard brought the body to the East Room, where funeral ceremonies were held the following day. “My boy! My boy!” cried Lincoln at the sight of the body. “Was it necessary that this sacrifice should be made?” Ellsworth’s men were so aggrieved that they had to be confined to a ship anchored in the middle of the Potomac, to be certain that they would not burn Alexandria to the ground. As the body lay in state at the White House, Lincoln composed a poignant letter to Ellsworth’s parents. “In the untimely loss of your noble son, our affliction here is scarcely less than your own,” he wrote. “In the hope that it may be no intrusion upon the sacredness of your sorrow, I have ventured to address you this tribute to the memory of my young friend, and your brave and early fallen child. May God give you that consolation which is beyond all earthly power.” In the days to come, the phrase “Remember Ellsworth!” became the rallying cry of Union recruitment drives, and a regiment known as “Ellsworth’s Avengers” was raised in his native New York. “We needed just such a sacrifice as this,” declared one clergyman. “Let the war go on!”

The death of Colonel Ellsworth in Alexandria, Virginia.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

* * *

IN BALTIMORE, THE FIRST CASUALTIES

of the war had already fallen. On the morning of April 19, a thirty-five-car military train had departed Philadelphia on Samuel Felton’s railroad, answering President Lincoln’s call for troops to reinforce the capital. On board were seven hundred well-equipped soldiers of the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, as well as several companies of Pennsylvania infantrymen, who had not yet been issued arms or uniforms. In order to reach Washington, the troops would have to follow the same path through Baltimore that Lincoln had taken two months earlier, arriving at the President Street Station and passing through the center of town to Camden Street.

Trouble was expected. “You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and perhaps assaulted,” the men were told. They were ordered to pay no attention, and to continue marching with their faces to the front, even if pelted with stones and bricks. Should they be fired upon, however, their officers would order them to return fire. If this should occur, the men were instructed to target any person seen with a weapon and “be sure you drop him.”

On arrival at the President Street Station, it was decided that the troops would not march through the streets in columns, as expected. Instead, the train cars would be drawn through the city by horse while the soldiers remained inside, perhaps to avoid a provocative display of military force. For a time, all appeared well. The first few cars reached Camden Street, wrote Baltimore’s mayor, George Brown, “being assailed only with jeers and hisses.” As each successive car passed through the streets, however, the crowds of onlookers swelled, and “the feeling of indignation grew more intense.” Soon, paving stones and bricks were thrown, breaking the windows of the train carriages and striking some of the soldiers inside. Elsewhere, a group of “intemperate spirits” dumped a cartload of sand in the path of one of the carriages, while others dragged heavy anchors into position from a nearby dock. The progress of the troop cars came to a halt.

When word of these obstructions reached the President Street Station, the remaining troops climbed down from their carriages and formed into columns, preparing to march through the center of town, come what may. By now, word of the movement of the soldiers had spread to every corner of the city. As the marchers advanced onto Pratt Street, an ever-growing mob of angry citizens threatened and pressed from both sides, “uttering cheers for Jefferson Davis and the Southern Confederacy, and groans for Lincoln and the north, with much abusive language.” Soon, a Confederate flag appeared, spurring the crowd to greater extremes. As the columns of marchers skirted the docks, a shower of stones and bottles rained down, and two soldiers fell to the ground, seriously injured. Officers now ordered the men to a “double-quick” pace, in hopes of passing through the mob before the situation worsened. This action, according to one soldier’s account, seemed to throw fuel on the crowd’s rage.