Read The Indifferent Stars Above Online

Authors: Daniel James Brown

The Indifferent Stars Above (25 page)

Donner Lake as seen from the crest of the Sierra Nevada; the lake camp was in the woods at the far end of the lake.

The Murphys and Fosters built their cabin at the lake camp against this boulder.

Donner Pass at the left, as seen from the cliffs west of Donner Lake.

Arrival of a relief party at the lake camp.

Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California-Berkeley

Tall stumps cut at the level of the snow by the Donner Party or a relief party, likely at Starved Camp.

Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California-Berkeley

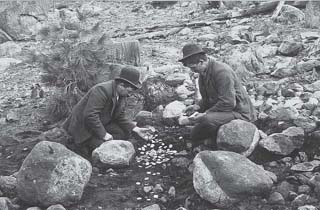

Discovery of Elizabeth Graves's coins on the shores of Donner Lake in 1891.

Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California-Berkeley

The death of Franklin Graves as depicted in

Graham's Illustrated

magazine, February 1857.

The woman was Levinah Murphy, whose son John had died on January 30. In the past few days, she had watched first the baby Margaret Eddy, then Margaret's mother, Eleanor, and then Milt Elliott all die in her miserable cabin built up against the gray, cold boulder.

Reason Tucker and his men went quickly among the survivors, doling out small portions of food in the failing light of dusk. Tucker and his men were horrified by what they beheld. These people were walking cadavers. He and his men, he said, “cried to see them cry and rejoiced to see them rejoice.” The picked-over bones of oxen and putrefied bits of ox hide lay about on the snow. Worse, human bodies also lay scattered about, half covered by snow or by quilts. To get the bodies out of the cabins, the women and children who now mostly inhabited them had had to dig inclined planes and drag them up and out. They had not then had enough strength remaining to bury them any deeper than under a light cover of snow.

Tucker pushed on to the Graveses' cabin a half mile to the northeast and arrived there in the dark at about 8:00

P.M

. He found the double cabin, like the others, buried under more than a dozen feet of snow. But it was a clear night, and a crescent moon hung in the western sky. He could make out a column of smoke rising from a hole in the snow. When he called out, an emaciated Elizabeth Graves and her children crept up out of another hole. She scanned the faces of the men assembled in front of her in the moonlight and asked where Franklin was, whether he and Jay and Sarah had gotten through. Tucker did not have the heart to tell her the truth. He said that they had all arrived safely but that their feet were too frozen to allow them to return.

*

Elizabeth Graves didn't buy a word of it, though. If Franklin had not come back, it must be because something dreadful had happened. For now, though, she could only imagine just how dreadful.

The next day Tucker and some of his men continued on to the Alder Creek camp, where they found an even more dismal scene. Hunkered down in their tattered tents with only a single ox hide left between them, Tamzene and Elizabeth Donner had for days now been watching their twelve children, ages three to fourteen, slowly approach starvation. With Jacob Donner dead, George Donner bedridden with his infected arm, and most of the teamsters dead, the two mothers and Doris Wolfinger had had only three teenage boysâJean Baptiste Trudeau, Noah James, and Solomon Hookâto help them with the heavy and relentless work of cutting wood and shoveling snow off the tents.

Tucker and Rhoads explained to the women that they had been able to pack in only enough supplies to last a few days, but that they hoped other rescuers would be arriving soon. In the meantime they needed to take anyone healthy enough to endure the hike out of here. And they needed to do it now, before anyone got any weaker.

Both mothers faced agonizing choices. Elizabeth Donner had four children who were simply too young to have a chance wading through the deep drifts of snow, and there were not enough adults to carry them all. Tamzene had three of her own in the same situation. What's more, Tamzene would not hear of leaving George Donner here to die without her. They picked out a few older children who they thought might be able to make it outâElitha, Leanna, George Jr., and Williamâand handed them over to Tucker and his men. The rest of the children would have to stay with their mothers. The sixteen-year-old teamster Noah James would go, and so would Doris Wolfinger. But Solomon Hook would stay, and Jean Baptiste Trudeau was told he must, much against his will, stay to help cut wood for the women. The rescuers felled a large pine tree to give him a head start. They doled out small bits of beef and flour. Then, just hours after they had arrived, they led the children away from their desolate mothers and disappeared into the snowy woods.

The following day Elizabeth Graves had to make her own heartrending decisions. She still had four children aged eight or younger with herâeight-year-old Nancy, seven-year-old Jonathan, five-year-old Franklin Jr., and her infant, Elizabeth. She would have to stay in the

mountains to care for them. But twelve-year-old Lovina and fourteen-year-old Eleanor would go. Elizabeth wanted Billy to stay, to cut wood and do the heavy work, but he was bent, he said, on getting over the mountains and bringing food back for his little brothers and sisters. Elizabeth relented and said he could go. If Franklin was dead, as she must have suspected, Billy was her only assurance that someone would at least try to return for her and the younger children. That night he chopped and stacked a fresh supply of firewood for his mother.

Peggy Breen and Levinah Murphy made similar decisions. For the most part, the older children would go and the younger would stay. But there were exceptions. Two-year-old Naomi Pike, whose widowed mother was waiting for her at Johnson's Ranch and whose infant sister had died just two days ago, would go, Tucker and Glover announced. The men would carry her all the way. Twenty-three-year-old Philippine Keseberg had already lost one child here and wasn't willing to watch another die. She would leave her hobbled husband and carry her three-year-old Ada as far as she could.

Margret Reed felt the same way. With no remaining resources of her own, reduced to eating the Breens' cast-off bones, she was going, and so were all her children, even three-year-old Thomas. As long as they could walk, they were going to get out of there, or die trying.

John Denton, the English gunsmith, like many of the single men, was weakening rapidly, but he, too, decided he would go.

Â

A

nd so on the morning of February 22, the men of the First Relief stood in the snow at the eastern end of the lake, surrounded by children and grief-stricken mothers with hollow faces who clutched their children and wailed and then finally let them go. They trudged off into the snowâtwenty-two of themâa long procession mostly composed of children and large men.

They had not gone far, though, before three-year-old Thomas Reed and eight-year-old Patty Reed gave out. Tucker and Aquilla Glover told Margret Reed the two children would have to go back to the cabins. Months later Virginia Reed described the scene in her letter to her cousin Mary.

O Mary that was the hades thing yet to come on and leiv them thar. [We] did not now but what thay would starve to Death. Martha [Patty] said, well ma if you never see me again do the best you can. the men said thay could hadly stand it. it maid them all cry.

When Patty and Thomas had been returned to the Breen cabin, the First Relief continued on its way, crossing the frozen lake, wading through deep snow. Exhausted and famished by the effort, they eagerly ate the remainder of their dried beef that night, knowing that they had cached a good deal more up at the pass for the return trip. The next day they scaled the cliffs at the western end of the lake. Nearly all of the men carried children, but still there were many children who had to walk. Six-year-old James Reed Jr. was up to his waist in the snow, but somehow he kept going, clambering over ice-slick boulders and wading through deep drifts of powder. With every step, he told his sister Virginia resolutely, he was “getting nigher Pa and somthing to eat.”

On the evening of February 23, they reached the pass and the platform of logs that they had built on the way in. But when they got there, they found trouble. When they had left their cache of food here, they had secured it from animals, probably by tying it in a bundle and suspending it from the end of a branch in a pine tree, out of reach of bears. But they had not reckoned on smaller and more agile animals like martens and fishers, who could climb to the ends of the pine branches. The cache had been ripped open, the food consumed or dragged away.

Alarmed, Tucker immediately announced that for the remainder of the trip everyone would be on short rations. From that moment forward, Tucker feared for all their lives. “Being on short allowances,” he confided in his notes, “death stared us in the face.”

On the morning of February 24, following the burned-out snags they had left behind on their ascent of the mountains, the First Relief resumed moving west. After a mile or two, though, John Denton began to fall behind. Reason Tucker held back, waiting for him, but the young Englishman had grown weak and snow-blind, and it was clear that he could not continue. The others could not wait for him. Tucker built a platform of pine saplings and kindled a fire on it for him. He

sat the young man down, took an expensive coverlet from his own backpack, and wrapped him in it. Tucker assured him that help would arrive soon, though both men must have known that there was little prospect of that. Then Tucker walked on down the trail and rejoined the others. When Denton's body was eventually found, it had been half consumed by animals.

They traveled on down the Yuba River. Thus far they had been fortunate enough to have fair, warm weather, but the warm afternoon sun exacted a price, thawing the crust of the snow and making walking much harder. Three-year-old Ada Keseberg couldn't manage it at all. Her mother had carried her for as long as she could. Then John Rhoads had carried her, but by that evening Ada Keseberg was failing. In the bitter cold of that night, she died.

When it was time to push on in the morning, Philippine Keseberg, who had seen her only other child buried in the snow back at the lake camp, would not part with her daughter's body. She sat clutching Ada to her breast, would not relinquish her, would not move on without her. Finally, as most of the others began to trudge away, Tucker sat down with her: “I told her to give me the child and her to go on. After she was out of sight, Rhoads and myself buried the child in the snow best we could. Her sperit went to heaven her body to the wolves.” Then they continued along the Yuba and camped that night under the granite knob now called Cisco Butte.

By the middle of the next day, February 26, their provisions had grown so short that for a midday meal they resorted to toasting rawhide shoestrings. But Glover and John Rhoads had gone ahead looking for signs of a second relief effort, and shortly after eating the shoestrings, Tucker and his band of survivors came across two men with packs trudging through the snow toward them. Glover and Rhoads had indeed found a second relief party a few miles ahead and sent the two men back with dried beef. Billy, Lovina, and Eleanor Graves and Tucker's other famished survivors sat down in the snow and feasted. And to make the meal all the sweeter for Margret Reed, the men who had brought the supply of dried beef had also brought news that filled her heart with joy. The Second Relief, now just a few miles down the trail, was headed by James Reed.

At about the same time, Reed learned from Glover and Rhoads that his wife and two children were alive just up the trail.

Â

J

ames Reed had lived an adventurous life since last he saw his wife. After failing to get through the mountains in his first effort to reach his family in October, he had returned to Sutter's Fort looking for help. But he could not have arrived at a more inopportune timeâall the able-bodied American men in the area had by now rushed south to join John Frémont and fight against Mexican forces still resisting the occupation of California. Unable to procure sufficient men or supplies for another rescue attempt, Reed put aside any immediate plans to effect a rescue and went instead to the American-held Pueblo de San José, where he enlisted as an acting first lieutenant in a volunteer company. While waiting for military action and pondering his next move, he petitioned the new American alcalde of San Jose, John Burton, for a large tract of land in the heart of the Santa Clara Valley, the second land petition he had filed in California in a little over a month.

On January 2, near Mission Santa Clara, Reed and a small detachment of men under his command joined a larger force of about eighty-five, closed with roughly one hundred fighters under the command of Don Francisco Sánchez, and engaged in a brief skirmish. An hour later one or two Americans were wounded, five Californians were wounded, three Californians were dead, and the Californians had surrendered. Using his saddle as a desk, on January 12, Reed wrote exuberantly to Sutter about his role in the battle.

I have done my duty and no more; but I am still ready to take the field in her cause, knowing that she is always right. I tell you, my friend, many were the dodges I made with my head from the balls that whistled by meâ¦.

After what came to be called, somewhat vaingloriously, the “Battle of Santa Clara,” Reed rode north to San Francisco, where he petitioned first U.S. naval authorities and then the general citizenry of the burgeoning American hamlet for aid in rescuing the Donner Party. The

citizens responded with more than a thousand dollars, the navy with a promise to supply matériel and logistical support. A navy midshipman, Selim E. Woodworth, agreed to lead the effort to transport goods into the mountains with a contingent of navy men.

Meanwhile, William McCutchen had made his way to the Napa Valley, where he, too, was gathering supplies for an effort to rescue his infant daughter, Harriet, and the others still in the mountains. On January 27 he wrote Reed, somewhat testily, “You had better come in haste as there is no time to delay.” He wanted to get under way by February 1.

But it was February 19 by the time that Reed had rendezvoused with McCutchen, driven a string of horses to Johnson's Ranch, and begun slaughtering cattle and drying strips of beef. On February 21 some of the men who would make the attempt caught up with Reed and McCutchen at Johnson's. Among them was a familiar faceâHiram Miller, who had been a teamster for the Donners back on the plains before going ahead with the Russell Party. Selim Woodworth, they reported, had paused at Sutter's Fort, and they could not say when he would arrive.

The next morning Reed told Johnson to inform Woodworth that he had gone ahead without him and to follow on his heels as soon as possible. Then, with about two hundred pounds of dried beef, seven hundred pounds of flour, and more than two dozen horses, Reed, McCutchen, and the men of the Second Relief left Johnson's Ranch and started up the Bear River.