The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (15 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Visualize Edmonia at such a gathering, welcomed by Miss Cushman and introduced to other guests. Eventually the actress clapped her hands and said that friends asked her to read, but first she wanted everyone to know an important newcomer to Rome. She summoned Edmonia to her side with a dazzling smile and a grand beckoning hand, put an arm around her, and began her introduction:

The talented young sculptor who portrayed heroic Col. Shaw in a bust so marvelously that one hundred copies were sold; the child of the forest who came to Florence and was helped by Hiram Powers, Thomas Ball, and Harriet Hosmer; the colored sculptor who chose to depict the day of Emancipation as her first work in Italy,

The Freed Woman and Her Child on Hearing of Her Freedom;

an orphan who had to survive on what she sold, who was starting out in the very studio Canova occupied and indeed where Miss Hosmer studied with John Gibson. I wish to present Miss Edmonia Lewis!

The sentimental tale told by a dramatic master mesmerized the adoring audience. Now, I’ll read a poem by Anna Quincy Waterston in honor of Miss Edmonia Lewis.

At the ovation, a blush and a broad smile broke through Edmonia’s wariness. So many people introduced themselves she could not keep track. At the end of the evening, Edmonia sincerely thanked Miss Cushman, who was beaming. She was a protégée again and the hit of the evening. People shook her hand and surely complimented her outfit. Did she wear Mrs. Child’s silk gown? We will never know.

Miss Cushman was as powerful and her life as complex as the Shakespearian roles she inhabited on stage. Her skill and spirit could bewitch whole rooms of people. In her day-to-day manner, there was nothing theatrical about her. She was clearly authoritative and intelligent. She was in great need of love – unalloyed, unquestioning approval. She had entertained seductive offers of marriage, but she had never formed an intimate relationship with a man.

Giving and getting love off-stage, she entrusted herself only to women. Many years before, a distinguished Philadelphia portrait painter, Thomas Sully, had shown her as a smiling young woman, softening her features and making her look quite beautiful.

[171]

She developed an intense love affair with Sully’s daughter, Rosalie. Even after Charlotte’s career separated them, glowing letters sustained the relationship until Rosalie’s passing in 1847.

[172]

The provocative writer, Geraldine E. Jewsbury, met Charlotte in England. Her novel,

Zoe, A History of Two Lives,

had shocked many people because of its discussion of religious doubts and restrictions on women. She then based the main character of her 1848 novel,

The Half Sisters,

on Charlotte. The two artists found in one another understanding, passionate appreciation, and protective love.

It was to Geraldine that Charlotte confided her near seductions. Separated by touring appearances, Geraldine accepted Charlotte’s need for constant intimacy. When Charlotte confessed to being troubled by her relationship with Eliza Cook, a beer-drinking young poet who dressed in ‘staring’ red and cut her hair in a mannish style, Geraldine counseled: “Now for what you darkly allude to, I know something of that worry too ... follow your own instincts. You need love to keep you up in your daily course more than other women …” Geraldine concluded: “Miss Cook would think me very good if she could believe that another person might love you as well as she does.”

[173]

More affairs followed. In 1849, tall, attractive Matilda Hays

[174]

asked to be her apprentice, playing Juliet to Charlotte’s Romeo. Matilda eventually gave up acting, but she continued as Charlotte’s constant companion for a decade. Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote to her sister: “I understand that she and Miss Hays have made vows of celibacy and eternal attachment to each other – they live together, dress alike … It is a female marriage.”

[175]

A friend assured her the arrangement was “by no means uncommon.”

Later in Boston, enchanted with the outgoing Hatty Hosmer, Charlotte convinced the budding sculptor’s father to let his daughter study in Rome. Hatty soon inhabited her own rooms at Charlotte’s Corso address.

[176]

A year or so later, Charlotte discovered that Hatty and Matilda had developed a relationship that excluded her. She rather desperately turned back to the theater and sought new relationships.

By the time Edmonia appeared, Charlotte was a forgiving maternal figure – ‘Ma’ – to Hatty. She had formed the most stable relationship of her life with the adoring Emma Stebbins, a painter-turned-sculptor from a wealthy New York family. Reserved and a year older, Stebbins provided a perfect complement to the gregarious actress.

Hatty once called Emma, who also studied with Gibson, “wife.”

[177]

But it was with Charlotte that Emma shared rooms when they moved to Via Gregoriana in 1858. Hatty became “single,” living separately at the same address for several years.

Before Edmonia arrived in Rome, Charlotte and the headstrong Hatty were at odds. Hatty moved across the Piazza Barberini and next door to William Wetmore Story. Eventually, their resentments faded. They never regained their closeness.

Charlotte did not share Mrs. Child’s view that prolonged training and credentials must underpin serious art. She once worked as a utility actress, taking any role, even men’s parts. She advised young actresses to study as they performed: “You must suffer, labor, and wait before you will be able to grasp the true and the beautiful,” she told one young woman.

[178]

“... only practice can tell you whether you are right.” With similar advice to Edmonia, Charlotte could encourage her efforts to sustain herself with small sales while developing her craft.

Visitors soon brightened Edmonia’s day.

[179]

Keen to generate upbeat reports, eager for sales, and proud of her work, she would have welcomed them. Smart and cheerful in her own shop, Edmonia was ready to answer questions, even complying when people coyly asked to see her sculpt. They doubted that a woman could actually create something original. Hatty, who had suffered such taunts to the point of exasperation, was protective of her sister artists. She undoubtedly prepared Edmonia for such skepticism.

Stimulated by the attention, needing something new to show, Edmonia must have modeled wet mud in her dreams. Each day, she headed past the Spanish Steps to her studio, anxious to work. She might periodically digress to clear her mind, walking about like a tourist, visiting Hatty’s studio, or casting medallions for ready sale. Plaster was easy and inexpensive – and she needed income. She hired local carvers, probably recommended by Hatty, to put her commissions into marble. After studying their techniques, she could help with polishing. One day she would take over chisel, rasp, and file.

Visionary chatter about the “noble savage,”

[180]

mythical and real, must have sparked great interest among Edmonia’s fans. Joseph Mozier, whose studio was near Hatty’s, had enjoyed success carving versions of a semi-nude

Pocahontas.

At Edmonia’s request, Mrs. Child sent her notes on the legendary princess, later commenting, “I thought it would be a good subject for her because she had been used to

seeing young Indian girls

, and could work from

memory

, and with her

heart

in it, for her mother’s sake.”

[181]

Edmonia found greater promise in

Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow’s

Song of Hiawatha

(1855). The epic poem was a huge best seller world-wide.

[182]

Its insistent pulse, exotic story, magical beings, and inspired images were so romantic, so exciting. Was it to advance his mission – or the cravings of youthful desire – that led Hiawatha to discard the advice of old Nokomis? Hiawatha swept the young Minnehaha off her maidenly feet while her father looked on with pride.

Longfellow depended upon readers’ imaginations to conjure scenes of primal love in the wilderness. The tender union also settled an important conflict between their tribes, resonating with a national wish for harmony as North-South tensions grew. Then, like the lost Lenore of Poe’s

Raven

(1845), the beautiful young woman tragically died. Magnified by readers’ sympathy, the self-reliant Hiawatha fulfilled his task alone.

The effect was charming and popular. People dwelled on tragedy and wished for simple solutions to modern troubles. Currier & Ives had recognized a ready market with a series of Hiawatha prints, two each illustrating his wooing and wedding.

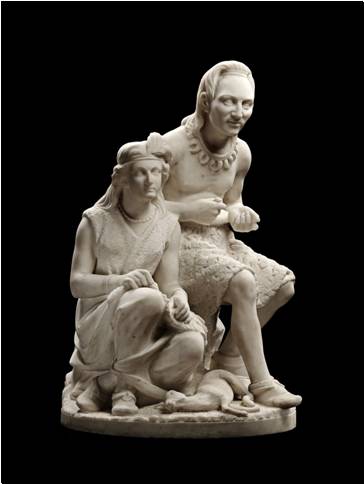

Edmonia roughed out scenes from the same passages in three dimensional clay. She again plunged into the problems of two-figure designs. She started

Hiawatha

’s Marriage

[184]

(Figure 9) while working on

The Freed Woman.

A wealthy matron, sister to an art collector, ordered a copy while it was still in clay.

Soon a companion group,

Hiawatha’s Wooing

(later called

The Old Arrow Maker)

[185]

caught buyers’ eyes. (Figure 10)

Unlike sculptors for whom the “noble savage” excused bare flesh to pique the appetites of the mostly male market,

[183]

she used thrills of modest but exotic clothing and the mystique of love to elicit orders from women. Each statue was about two feet tall, a handy scale that accommodated her market, was not overly dear, and fit strong tables in well-appointed parlors. In size, they were well within the range used by John Rogers for his popular plaster illustrations.

In no time at all, the public showered its approval.

[187]

One observer raved, “In both the Indian type of feature is carefully preserved and every detail of dress, &c. is true to nature: the sentiment is equal to the execution. They are charming hits, poetic, simple, and natural, and no happier illustrations of Longfellow’s most original poem were ever made than these….”

[188]

Another went further, “The pose of Hiawatha and Minnehaha is perfectly natural; there is an ease and gracefulness which is really charming. The adjuncts are also in keeping: the wampum belt, the fringe on the robe, the quiver and arrows, the wild flowers on the ground; the whole

tout ensemble

carry out the idea and illustrate Indian life.”

[189]

Figure 9.

Hiawatha’s Marriage,

modeled 1866

Except for exotic costumes, the figures in Edmonia’s illustrations of

The Song of Hiawatha

might be European. The above copy was carved in 1874. Photo courtesy: Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas.

[190]

Figure 10.

The Old Arrow Maker,

modeled 1866, carved 1872.

From the first, this image was also called

The Wooing of Hiawatha.

[191]

Photo courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Joseph S. Sinclair.

Hinting at benefits she might deliver, the celebrated actress danced a dance Edmonia had learned in Boston. Charlotte understood how to precipitate news and move buyers. She connected to important people and was wise from a lifetime in the arts. She was also more skilled as a mentor, more stable, more realistic about art, and unafraid of critics. She once promoted Hatty this way, when her retirement was fresh and she had few worries, then Emma Stebbins. Now older and less personally involved, she still enjoyed triumph by proxy.

Unlike Charlotte’s close admirers, Edmonia never felt the actress’s dramatic powers until she attended her first ‘evening.’ She was also not schooled in writing the adoring ‘love-you’ notes the actress craved. Neither her stone-faced aunts nor her prim circle in Boston – and certainly not the Oberlin perfectionists – indulged in the personal superlatives that Charlotte eagerly consumed.