The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (18 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

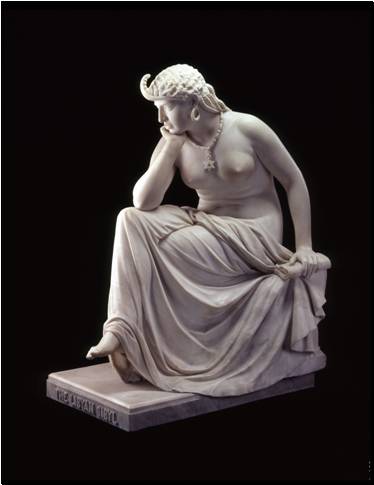

His fame as a sculptor followed the 1862 London world’s fair where he stirred admiration with two life-size statues:

Cleopatra

(Figure 35) and

The Libyan Sibyl

[225]

(Figure 14). Both innovated smartly on African themes. Both evoked the issues of race and bondage that were fraying the tissues of society across the Atlantic. America had just entered the second year of its bloodiest war. Emancipation had not yet been proclaimed. A New York critic exclaimed, “the truly splendid statues of the American, William Story, carry off the greatest applause.”

[226]

A year later, Harriet Beecher Stowe declared that

she

had inspired Story’s

Libyan Sibyl.

Writing for the

Atlantic Monthly,

she revealed how she, as Story’s houseguest, had moved him with tales of the famous freed slave turned evangelist:

The history of Sojourner Truth worked in his mind and led him into the deeper recesses of the African nature, – those unexplored depths of being and feeling, mighty and dark as the gigantic depths of tropical forests, mysterious as the hidden rivers and mines of that burning continent whose life-history is yet to be. A few days after, he told me that he had conceived the idea of a statue which he should call the Libyan Sibyl … Two years subsequently, I revisited Rome… Mr. Story requested me to come and repeat to him the history of Sojourner Truth, saying that the conception had never left him. I did so; and a day or two after, he showed me the clay model of the Libyan Sibyl.

[227]

In the analysis quoted by Stowe and others, an

Athenæum

critic noted the statue’s crossed legs and closed mouth to conclude the “secret-keeping dame” represented the African mystery. Yet Sojourner Truth was never about mystery, secrecy, or Africa. She was a charismatic American who happened to be born in New York State, colored, and a slave. Having escaped bondage as an adult, she had electrified audiences, preaching her gospel of freedom and feminism. She often cried, “Well children, I talk to God and God talks to me!” She could demonstrate a strength equal to most men and then ask, “Ain’t I a woman?”

The mystery should have been why Story’s

Sibyl

was so gloomy. Where was the “triumphant” feeling and “overwhelming energy” that Stowe described? Story’s downward looking

Sibyl

was nothing like Stowe’s description: “stretching her scarred hands towards the glory to be revealed.”

Story never confirmed Stowe’s claim in print. Obviously narcissistic, he was unlikely to share credit for his art. He called his

Sibyl

a prophet of ancient Greek myths. His description, below, tells us less about his subject than it does about him and his circle, an elite society that shared a romantic pride based upon insularity, shallowness, and confusion:

She is looking out of her black eyes into futurity and sees the terrible fate of her race. This is the theme of the figure – Slavery on the horizon, and I made her head as melancholy and severe as possible, not at all shirking the real African type.

[228]

Then he shrugged off his racial intent: “On the contrary, it is thoroughly African – Libyan Africa of course, not Congo.”

The woozy muddle between the living preacher and the mythical Sibyl was not surprising for an artist who framed his visions exclusively in white marble with a devotion to classical Greece. Story’s art was inseparable from the pecking order that put the black African at risk and out of sight. His instincts shared the essence of Child’s objections to the realism of

The Freed Woman.

An equal barrier existed between his idea and the facts of slavery present and past. An ancient Libyan vision of “slavery on the horizon” could more reasonably have pointed to the pirates who once sailed from Tripoli, Tunis, etc. – North Africa’s Barbary Coast. For hundreds of years, they kidnapped over a million white Europeans and sold them into slavery. The mythic prophet might have also foreseen U.S. Marines storming Libyan shores in 1804 – then bragging and singing about it. But then, for Story’s crowd, the Barbary pirates were out of fashion.

Stowe’s article was widely read. The nickname ‘Libyan Sibyl’ still clings to Sojourner Truth.

Figure 13. Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth’s portrait appeared in the frontispiece of her

Narrative,

published in 1850. She exposed her breasts to women and said she had suckled “many a white babe”

when anyone doubted her gender.

[229]

Figure 14.

The Libyan Sibyl,

by William Wetmore Story

Marble, modeled 1861, carved 1868, 57 in. in height.

Photo courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, bequest of Henry Cabot Lodge through John Ellerton Lodge.

The Africa reference helped make William Wetmore Story famous during the American Civil War. He

considered the six-pointed pendant hanging from the Sibyl’s neck mystical, a “cabalistic sign of supreme rank” traceable to Egypt and a symbol of the Star of Bethlehem.

[230]

For English and American artists in Rome, Story was the alpha dog of their habitat. His spoor seasoned their air as he took pains to despise them. He was, according to Anne Whitney, known as a snob.

[231]

He sniffed to an old friend, “For the most part, and with scarcely an exception among the American artists, art is (here) but a money-making trade, and I can have no sympathy with those who are artists merely to make a living. As for general culture there are none of our countrymen here who pretend to it….”

[232]

When he settled in Rome in 1856, he took offense that Charlotte Cushman failed to call on him. It was a critical sign of status. Hoping to impress her, he had visited her when she moved in several years earlier. He then claimed he helped her and Hosmer find their way. Forced by Cushman’s fame to eventually pay his respects, he never forgave her, squalling to anyone who would listen. Years later, he sniped in a letter, “Miss Cushman is mouthing it as usual, and has her little satellites revolving around her.”

[233]

Story’s wife, according to Anne Whitney, was fully engaged in the feud.

[234]

Although Story later became friendly with Harriet Hosmer (after she left Cushman’s building to move in next door), he once disparaged her along with the rest. He believed women artists were drones: “It is one thing to copy and another to create. [Hosmer] may or may not have inventive powers as an artist, but if she have will she not be the first woman?”

[235]

Such congealed biases mired gender equality in art for another hundred years in spite of ample evidence to the contrary.

Story’s biographer, Henry James later turned bits of the rivalry into quotable phrases. He famously labeled Cushman’s circle, “that strange sisterhood of American ‘lady sculptors’ who at one time settled upon the seven hills in a white marmorean [“marble”] flock.”

[236]

Singling out Edmonia for special abuse, he ignored her name in favor of a sneering figure of speech, “One of the sisterhood, if I am not mistaken, was a negress, whose colour, picturesquely contrasting with that of her plastic material, was the pleading agent of her fame.” In James’s view, none of the “strange sisterhood” could achieve the immortality that he supposed was Story’s due.

In spite of egalitarians in their midst, Story and his crowd epitomized the class custom that kept Edmonia’s people down. Their status depended more on a sustained pretense of entitlement – more like European aristocracies than post-revolutionary Americans. They reveled in catty snipes and customs as proof of their own worth. Story crowned his descriptions of popish Rome, for example, with gritty stereotypes of beggars as Jews – ghettoed, overtaxed, and stigmatized as a second-class race.

[237]

In spite of his friendships with Senator Sumner and other ardent abolitionists, he callously spun himself as a

victim

of slavery. James later excused him “as rather pitifully ground between the two millstones of the crudity of the ‘peculiar institution’ on the one side and the crudity of impatient agitation against it on the other.”

[238]

Oddly, Sumner never got a whiff of this, for in 1864, he announced to Story, “You will be happy to know that the fate of Slavery is settled. This will be a free country.”

[239]

Then, Sumner urged his friend, “Be its sculptor. Give us, mankind, a work which will typify or commemorate a redeemed nation. You are the artist for this immortal achievement.”

The Story name had clouded Edmonia’s horizons long before she sailed. It was celebrated in his native Salem. Around greater Boston, he was a local blue blood. Mrs. Child cited his

Libyan Sibyl

when admiring Edmonia’s

Shaw

for the

National Anti-Slavery Standard.

[240]

At the close of the Civil War, Story and his wife visited Boston and Newport for a few summer weeks. They hobnobbed with old friends at events public and private as Edmonia prepared to go to Italy. Pompous and hypercritical, they counted Stebbins’ new statue of Horace Mann and the Harvard graduation among many dislikes.

[241]

Ample opportunity existed for Edmonia’s backers to engage Story’s aid as they did Seward and others. If any such attempts were made, only rumors survive. More likely, he waved them off with unsubtle scorn.

After Edmonia arrived in Rome, word of his disdain for other artists could have reached her via Hatty, Charlotte, and their friends. She must have judged him spoiled by a society of privilege, prejudice, and conceit.

One day, as she worked on a portrait outside Boston, she would point to the affable curiosity of an infant belonging to a wealthy family, the Forbes. The baby studied their different skin colors for some time, putting her hand on Edmonia’s cheek. “Kiss me,” the baby told her. Delighted, she observed that the two-year old’s warmth toward her showed no natural bias against her dark skin.

[242]

Edmonia, raised to maintain a stoic dignity, was tested by ordeals at Oberlin, by skeptics in Boston, and competitors in Rome. She must have pondered Story’s fame. He existed outside her immediate circle, not a threat. Her time would come. She did not miss much, but she would not miss dinner at the Palazzo Barberini.

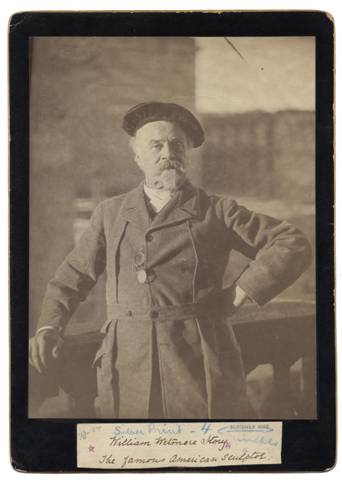

Figure 15.

William

Wetmore

Story, ca. 1870

Unidentified photographer, Charles Scribner’s Sons Art Reference Dept. records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The Curse of the “Negro Wench”

Soon enough, Edmonia learned

The Freed Woman

had failed. Funds for marble would not come. The turnabout must have been a shock, a scary step into space that had promised firm footing. For months Child, the Waterstons, Stevenson, Cheney, and others – not to mention the press and friends in Rome – had outdone each other with encouragement. The core of Mrs. Child’s rant, which reviled the woman’s figure, must have filtered through – perhaps interpreted by Hosmer, Peabody, or others wise in the ways of that society. In retrospect, it seems Edmonia surmised that this was where she had gone wrong.