The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (23 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Edmonia told her that German neighbors were always sympathetic and helpful.

[321]

Later that year, Prince George of Prussia would order a statue of

Clio,

the Greek muse of history.

[322]

No one, of course, outranked Charlotte Cushman in Edmonia’s gratitude. She planned a fine portrait to be sold in plaster as well as in marble.

[323]

Miss Peabody, a vigorous partner in the struggle against slavery, found the new emancipation statue particularly exciting and timely. Edmonia told her she had dedicated it to William Garrison and asked that it be paid for only by colored Americans. Miss Peabody later cooed, “[that] clothed it with so much sacredness that it made a cold critical analysis impossible. It went to my heart, as it came from hers.”

[324]

More than a year earlier, Edmonia had sent a photo of it to fans in America, hoping to rally support. Ednah Dow Cheney renewed her sense of promise, predicting, “if [Edmonia] keeps her simple nature amid the temptations of classic art, [she] may have a deep word for us.”

[325]

Mrs. Child was apparently eager to restore the bond torn by her attack on

The Freed Woman.

On Jan. 31, 1867, the

New York Independent

published her reaction to the new design, the first published description of it and an opinion laced with rosy optimism.

Even negroes, whom we have so long kept shut up in the dark cave of ignorance, are coming to a perception of the beautiful. At no other period of the world could

Edmonia Lewis,

half Indian and half African, have thought of becoming a sculptor, and been so generously encouraged in her thought. She has recently sent from Rome the photograph of a statue in commemoration of Emancipation. It represents a stalwart freedman, with shackles broken, raising one arm in thankfulness to heaven, and resting the other protectingly on the shoulder of his kneeling wife. The design is well conceived, and the manner of treating it does her so much credit that her patrons have reason to feel greatly encouraged concerning her ultimate success in the art she has chosen.

[326]

Is it any wonder that Edmonia’s confidence grew? Made bold by such words of praise and moved by a bearish hunger for recognition, she borrowed money for marble in Rome

.

[327]

The costs of good marble were steep or she might have gone for a much larger slab, one requiring the ladders and scaffolds used by Hatty and others. She settled on making the new statue more than forty-one inches high. (She stood barely seven inches taller herself.) Larger than

The Freed Woman

was,

[328]

its relative size suggests a growing confidence.

Before finishing, she discarded the original title, “Morning of Liberty,” and chiseled a more memorable phrase.

“

Forever Free

”

is a quotation from and the essence of the Emancipation Proclamation.

After finishing its polish, she carefully crated and shipped it to Boston. She was certain her New England fans would rejoice to share her vision in marble. It landed just as Miss Peabody arrived in Rome

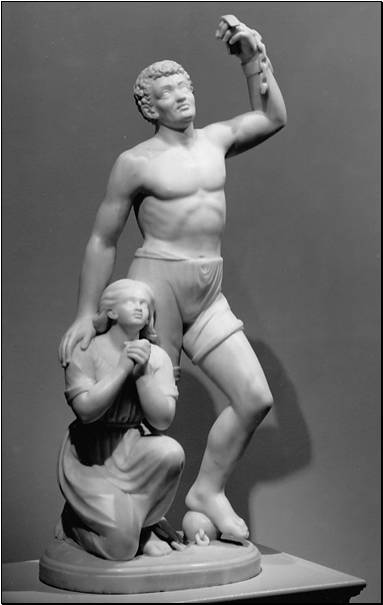

Figure 23.

Forever Free,

1867

Edmonia made her second “freed woman” in the context of family – i.e., under the protection of a man. Photo courtesy: Howard University, Washington DC.

Rare in its ability to reach out and sustain relevance, the image never required an elite education, a teacher, or a book to be an icon of the African-American struggle. It speaks of hope and the bittersweet taste of new freedoms. The day is won, but not the struggle. Chains are broken but not gone. Equality, justice, and true brotherhood are still beyond reach. Liberty is only a step toward the American dream.

Both figures yearn for the infinite ideal. Their upward gazes seek a common blessing. The modestly dressed woman oozes piety and trust. The pose of the nearly nude man shouts joy, strength, and the heroic resistance of militant abolitionists like Rev. Henry Highland Garnet. Natural and dynamic, the man challenges the status quo as he stands up to hierarchy, decorum, and tradition.

The man’s silhouette presaged the black power salute of the 1960s: a symbol of defiant solidarity. A hostile closed fist, of course, would not have been acceptable to Edmonia or her fans. Her affirmative soul and indirect tactics endeared her to the white buyers who supported her studio while infuriating the enemies of equality.

Her art espoused a thoughtful, righteous, persuasive approach, not angry threats. The war she waged, in modern terms, was “psychological.” No matter her warrior heroes, her line of attack was more akin to the militant civility of Frederick Douglass, Oberlin College, and Garrison’s

Liberator

than to John Brown’s armed rebellion.

For an artist lacking a master tutor, Edmonia’s command of the medium, the style, and human anatomy is quite special.

Forever Free

hews to neoclassical technique and structure if not its detail, reference and reserve. The carefully balanced composition forms a triangle from the man’s raised hand to the base. Each figure assumes an irregular stance. The polished marble looks less like stone than like flesh, metal, and cloth.

For a neoclassical-period sculpture, the immediacy, exuberance and anatomical details of

Forever Free

trampled custom as much as its direct reference to American field hands did. It stands in sharp contrast to the passive

Greek Slave

, the proud

Zenobia in Chains

, and even to the thoughtful

Freedman

. An American abolitionist who visited Edmonia’s studio in 1868 noted “her desire to catch the more spirited effects of a first impression, rather than to embody in the clay the harder likeness that comes to one as the features grow more tame by familiarity.”

[329]

Tuckerman’s writer also pointed out and praised her resistance to neoclassicism.

Later academics would seek to validate

Forever Free

as “neoclassical” by finding a Greek inspiration.

[330]

They then puzzled over her departures from antique ideals of anatomy.

Likely heartened by Ward’s entries in Paris, Ball’s Lincoln

bozzetto,

Hatty’s elaborate

Temple of Fame

model

[331]

– and her fans – Edmonia stressed her break with the classics by turning to America. She gave the man (but not the woman) sub-Saharan features and both figures large, strong, working class hands. The choices let African-American viewers recognize themselves, even in white marble. Crossing the color line was beyond the style – but beginning to be accepted in other American artists.

As the 1860s public expected an idealized – or non-realistic – symbolism, the racial incongruity passed without note for decades. Observers’ comments at the time ignored obvious details and took the woman in the group to be colored. Like the lost

Freed Woman,

her kneeling pose is more a symbol of Civil-War era politics than an homage to ancient Greek art. An 1866 marble by Edmonia marked

Preghiera

[“prayer” in Italian]

[332]

is nearly identical to the woman in

Forever Free.

In its separate context, it appears to convey a European theme.

Later generations became used to racial accuracy in the sculptures of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (born 1877), Augusta Savage (born 1892), Richmond Barthé (born 1901), and others. Eventually, they questioned the look of

Forever Free.

Freeman Murray’s 1916 study (the first) of Emancipation sculpture called the woman’s treatment “toning.” “As to physical features,” he noted, “Miss Lewis, in common with others who preceded her and others who followed her, seemed to feel called upon to ‘favor’ the woman in the group.”

[333]

He also quoted Meta Fuller, who took no issue: “The man accepts it (freedom) as a glorious victory, while the woman looks upon it as a precious gift.”

To suffragettes and modern feminists, the woman can speak for all women of the period – subject to male dominance and praying for their own rights.

[334]

By the time Edmonia shipped the statue to Boston, it was clear no woman would share equality with colored men. Many thundered with rage. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (seemingly unaware of Edmonia’s northern roots) saw it as a cue to claim suffrage for “the black women of the South” in her new political magazine, the

Revolution.

Whereas the lost

Freed Woman

had no man, the new statue seems to reflect the Victorian family, conservative, safe, and dependable.

[335]

Child and Peabody referred to the woman as “wife.”

[336]

(There are other symbolic possibilities. Rather than the usual inference of husband and wife, the racial mismatch could have echoed Edmonia’s well-known biracial parentage, father and daughter, or the idealized fraternity of brother and sister as suggested by art historian Hugh Honour.

[337]

No comments recorded during Edmonia’s lifetime hint at any of these ideas.)

More than likely, making the woman with white features was a practical concern for market preference – a lesson learned from the failure of

The Freed Woman.

The

Freedmen’s Record

seems to bear out this thought with a polite ambiguity. Calling the female “a young girl,” it remarked, “The design shows decided improvement in modelling the human figure, though the type is less

original and characteristic

[emphasis added] than in the ‘Freedwoman,’ which she sketched in the Spring.”

[338]

Elizabeth Peabody, who ardently backed Edmonia’s art, found a more poignant message: “The noble figure of the man, his very muscles seeming to swell with gratitude; the expression of the right now to protect, with which he throws his arm around his kneeling wife; the ‘Praise de Lord’ hovering on their lips; the broken chain, – all so instinct with life, telling in the very poetry of stone the story of the last ten years.”

[339]

That

was the reaction Edmonia must have counted upon when she impulsively decided to ship her second Emancipation tribute to Boston.

New England disappointed Edmonia again. Who would have thought the abolitionists who sent her to Rome as a VIP would so roundly reject her Emancipation studies? Was this not their dream? Did they not tell her so?

She later confessed, “When I came to Rome, I thought I knew everything, but I found I had everything to learn.”

[340]

Apparently referring to her art, the comment also seems to reflect the high cost of wisdom.

Mrs. Child and her friends could not have been more offended than if Edmonia had war-painted her face and danced buck-naked on the Boston Common. Nattering how ignorant and crude she was, they smarted at past associations with her.

Particularly chafed was the sixty-eight year-old Samuel E. Sewall, a Boston lawyer. He and his wife, Harriet, were dedicated abolitionists, contributors to the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society, and good friends of Maria Child. It was Samuel who received the mean surprise of cargo freight-collect in the short days of winter.

[341]

Topping the rude arrival were Edmonia’s bills totaling $800.

To keep the authorities from charging storage, then to auction the statue away, he had to rush to Boston harbor, pay $200, and then hire someone to haul it off the docks – but where? He had no interest in taking the unexpected artwork home. What should he do?

The well-established Alfred A. Childs & Co. gallery on Tremont Street, which had shown Edmonia’s

Dio Lewis

bust and Whitney’s

Africa Awakening,

agreed to take it on consignment and put it on display. The Boston Universalist magazine,

Ladies’ Repository,

quickly offered praise: “a beautiful and suggestive statuette … representing a colored man with his hands raised exultingly on account of his emancipation, and a colored woman kneeling near, her hands clasped in devout thanksgiving.”

[342]

Why Edmonia chose to address her shipment to Mr. Sewall we may never know. He probably led her on with charming words, soon forgotten by him, treasured by her. From Rome, she wrote to follow up and waited in vain for his reply.

She also sent photos of herself in work dress, a reminder of her solemn calling, to New England friends such as Anne Whitney’s sister and Adeline Howard, the aspiring teacher who had gone with her to Richmond.

[343]

Weeks later, she appealed directly to Mrs. Chapman, saying she had not heard from Mr. Sewall or any of her friends.

[344]

She desperately begged for help. She needed to pay bills.

After hearing of the Sewalls’ dismay, Child smoldered with embarrassment for months. Surely adding to her discomfort, her peculiar cycle of public joy repeated itself in print –

for all to see

– as she made private apologies for being Edmonia’s promoter.