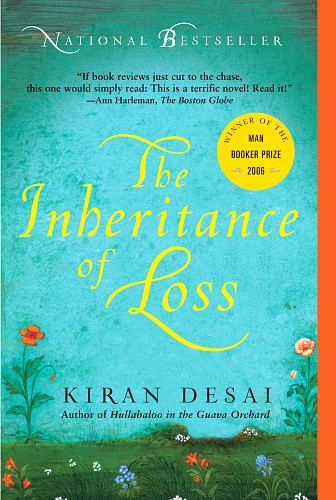

The Inheritance of Loss

The Inheritance

of Loss

Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard

The Inheritance

of Loss

Kiran Desai

PENGUI

N

CANAD

A

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsbeel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in Canada by Penguin Group (Canada), 200

6

Simultaneously published in the United States by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint o

f

Grove Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 1000

3

Copyright © Kiran Desai, 2006

"The Boast of Quietness," translated by Stephen Kessler, copyright © 1999 by Maria Kodama: translation © 1999 by Stephen Kessler, from SELECTED POEMS by Jorge Luis Borges, edited by Alexander Coleman. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Publisher's note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author's

imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

ISBN 0-14-305568-2

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication data available upon request.

American Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data available.

Visit the Penguin Group (Canada) website at

www.penguin.ca

To my mother with so much love

Boast of Quietness

Writings of light assault the darkness, more prodigious than meteors.

The tall unknowable city takes over the countryside.

Sure of my life and my death, I observe the ambitious and would like to understand them.

Their day is greedy as a lariat in the air.

Their night is a rest from the rage within steel, quick to attack.

They speak of humanity.

My humanity is in feeling we are all voices of the same poverty.

They speak of homeland.

My homeland is the rhythm of a guitar, a few portraits, an old sword, the willow grove's visible prayer as evening falls.

Time is living me.

More silent than my shadow, I pass through the loftily covetous multitude.

They are indispensable, singular, worthy of tomorrow.

My name is someone and anyone.

I walk slowly, like one who comes from so far away he doesn't expect to arrive.

—Jorge Luis Borges

The Inheritance

of Loss

One

All day,

the colors had been those of dusk, mist moving like a water creature across the great flanks of mountains possessed of ocean shadows and depths.

Briefly visible above the vapor, Kanchenjunga was a far peak whittled out of ice, gathering the last of the light, a plume of snow blown high by the storms at its summit.

Sai, sitting on the veranda, was reading an article about giant squid in an old

National Geographic.

Every now and then she looked up at Kanchenjunga, observed its wizard phosphorescence with a shiver. The judge sat at the far corner with his chessboard, playing against himself. Stuffed under his chair where she felt safe was Mutt the dog, snoring gently in her sleep. A single bald lightbulb dangled on a wire above. It was cold, but inside the house, it was still colder, the dark, the freeze, contained by stone walls several feet deep.

Here, at the back, inside the cavernous kitchen, was the cook, trying to light the damp wood. He fingered the kindling gingerly for fear of the community of scorpions living, loving, reproducing in the pile. Once he’d found a mother, plump with poison, fourteen babies on her back.

Eventually, the fire caught and he placed his kettle on top, as battered, as encrusted as something dug up by an archeological team, and waited for it to boil. The walls were singed and sodden, garlic hung by muddy stems from the charred beams, thickets of soot clumped batlike upon the ceiling.

The flame cast a mosaic of shiny orange across the cook’s face, and his top half grew hot, but a mean gust tortured his arthritic knees.

Up through the chimney and out, the smoke mingled with the mist that was gathering speed, sweeping in thicker and thicker, obscuring things in parts—half a hill, then the other half. The trees turned into silhouettes, loomed forth, were submerged again. Gradually the vapor replaced everything with itself, solid objects with shadow, and nothing remained that did not seem molded from or inspired by it. Sai’s breath flew from her nostrils in drifts, and the diagram of a giant squid constructed from scraps of information, scientists’ dreams, sank entirely into the murk.

She shut the magazine and walked out into the garden. The forest was old and thick at the edge of the lawn; the bamboo thickets rose thirty feet into the gloom; the trees were moss-slung giants, bunioned and misshapen, tentacled with the roots of orchids. The caress of the mist through her hair seemed human, and when she held her fingers out, the vapor took them gently into its mouth. She thought of Gyan, the mathematics tutor, who should have arrived an hour ago with his algebra book.

But it was 4:30 already and she excused him with the thickening mist.

When she looked back, the house was gone; when she climbed the steps back to the veranda, the garden vanished. The judge had fallen asleep and gravity acting upon the slack muscles, pulling on the line of his mouth, dragging on his cheeks, showed Sai exactly what he would look like if he were dead.

"Where is the tea?" he woke and demanded of her. "He’s late," said the judge, meaning the cook with the tea, not Gyan.

"I’ll get it," she offered.

The gray had permeated inside, as well, settling on the silverware, nosing the corners, turning the mirror in the passageway to cloud. Sai, walking to the kitchen, caught a glimpse of herself being smothered and reached forward to imprint her lips upon the surface, a perfectly formed film star kiss. "Hello," she said, half to herself and half to someone else.

No human had ever seen an adult giant squid alive, and though they had eyes as big as apples to scope the dark of the ocean, theirs was a solitude so profound they might never encounter another of their tribe. The melancholy of this situation washed over Sai.

Could fulfillment ever be felt as deeply as loss? Romantically she decided that love must surely reside in the gap between desire and fulfillment, in the lack, not the contentment. Love was the ache, the anticipation, the retreat, everything around it but the emotion itself.

________

The water boiled and the cook lifted the kettle and emptied it into the teapot.

"Terrible," he said. "My bones ache so badly, my joints hurt—I may as well be dead. If not for Biju. . . ." Biju was his son in America. He worked at Don Polio—or was it The Hot Tomato? Or Ali Baba’s Fried Chicken? His father could not remember or understand or pronounce the names, and Biju changed jobs so often, like a fugitive on the run—no papers.

"Yes, it’s so foggy," Sai said. "I don’t think the tutor will come." She jigsawed the cups, saucers, teapot, milk, sugar, strainer, Marie and Delite biscuits all to fit upon the tray.

“I’ll take it,” she offered.

“Careful, careful,” he said scoldingly, following with an enamel basin of milk for Mutt. Seeing Sai swim forth, spoons making a jittery music upon the warped sheet of tin, Mutt raised her head. “Teatime?” said her eyes as her tail came alive.

"Why is there nothing to eat?" the judge asked, irritated, lifting his nose from a muddle of pawns in the center of the chessboard.

He looked, then, at the sugar in the pot: dirty, micalike glinting granules. The biscuits looked like cardboard and there were dark finger marks on the white of the saucers. Never ever was the tea served the way it should be, but he demanded at least a cake or scones, macaroons or cheese straws. Something sweet and something salty. This was a travesty and it undid the very concept of teatime.

"Only biscuits," said Sai to his expression. "The baker left for his daughter’s wedding."

"I don’t want biscuits."

Sai sighed.

"How dare he go for a wedding? Is that the way to run a business? The fool.

Why can’t the cook make something?"

"There’s no more gas, no kerosene."

"Why the hell can’t he make it over wood? All these old cooks can make cakes perfectly fine by building coals around a tin box. You think they used to have gas stoves, kerosene stoves, before? Just too lazy now."

The cook came hurrying out with the leftover chocolate pudding warmed on the fire in a frying pan, and the judge ate the lovely brown puddle and gradually his face took on an expression of grudging pudding contentment.

They sipped and ate, all of existence passed over by nonexistence, the gate leading nowhere, and they watched the tea spill copious ribbony curls of vapor, watched their breath join the mist slowly twisting and turning, twisting and turning.

________

Nobody noticed the boys creeping across the grass, not even Mutt, until they were practically up the steps. Not that it mattered, for there were no latches to keep them out and nobody within calling distance except Uncle Potty on the other side of the

jhora

ravine, who would be drunk on the floor by this hour, lying still but feeling himself pitch about—"Don’t mind me, love," he always told Sai after a drinking bout, opening one eye like an owl, "I’ll just lie down right here and take a little rest—"

They had come through the forest on foot, in leather jackets from the Kathmandu black market, khaki pants, bandanas—universal guerilla fashion.

One of the boys carried a gun.

Later reports accused China, Pakistan, and Nepal, but in this part of the world, as in any other, there were enough weapons floating around for an impoverished movement with a ragtag army. They were looking for anything they could find—kukri sickles, axes, kitchen knives, spades, any kind of firearm.

They had come for the judge’s hunting rifles.

Despite their mission and their clothes, they were unconvincing. The oldest of them looked under twenty, and at one yelp from Mutt, they screamed like a bunch of schoolgirls, retreated down the steps to cower behind the bushes blurred by mist. "Does she

bite,

Uncle?

My God!

"—shivering there in their camouflage.

Mutt began to do what she always did when she met strangers: she turned a furiously wagging bottom to the intruders and looked around from behind, smiling, conveying both shyness and hope.

Hating to see her degrade herself thus, the judge reached for her, whereupon she buried her nose in his arms.

The boys came back up the steps, embarrassed, and the judge became conscious of the fact that this embarrassment was dangerous for had the boys projected unwavering confidence, they might have been less inclined to flex their muscles.

The one with the rifle said something the judge could not understand.

"No Nepali?" he spat, his lips sneering to show what he thought of that, but he continued in Hindi. "Guns?"

"We have no guns here."

"Get them."

"You must be misinformed."

"Never mind with all this

nakhra.

Get them."

"I order you," said the judge, "to leave my property at once."

"Bring the weapons."