The Interstellar Age (11 page)

Read The Interstellar Age Online

Authors: Jim Bell

The

Voyager

’s two-sided gold-anodized copper LP contains an hour and a half of music (27 pieces in all), 116 digitized photographs, and a catalogue of terrestrial sounds (such as the chirping of crickets) and voices (such as short greetings in fifty-five languages, including a “hello from the children of Planet Earth” in English from Carl Sagan’s six-year-old son, Nick). The record was housed inside a circular gold-plated aluminum casing to keep it protected from radiation, which could slowly weaken and corrode the metal, and from erosion by high-speed micrometeorites, which could more quickly pit and gouge it. A stylus (needle) and its cartridge are included nearby, along with other information and instructions on the outside of the case for how to play the record. With the vinyl-music era now fading into history, it is perhaps ironic that not just intelligent aliens but also most listeners of popular music today would require those instructions.

The number of musical pieces and pictures that could be

included was limited by the necessity of preserving the fidelity of the sounds and images while digitizing them to all fit on one double-sided record. Sagan and Ferris took charge of arranging the musical selections, Druyan was responsible for the sounds of Earth (all sounds outside of the musical selections), Salzman Sagan took charge of the multilanguage greetings, and Drake and Lomberg assembled the image collection, which consisted of digitized photographs and drawings, some of which were created by Lomberg himself when the images the team was looking for could not otherwise be found.

The 116 pictures are divided into two categories: photographs, and diagrams intended to teach the recipients how to comprehend the photographs. The photos were chosen with a single purpose: to convey information that is unique to our planet and its people. If the photos happened to also be artful, that was considered a bonus. The diagrams were there to provide information, mostly scientific and mathematical, that would explain things like the composition of the air we breathe here on Earth. In fact, the first diagrams that our future extraterrestrial friends would encounter were etched into the cover of the record case itself. The Golden Record was mounted on the front of the spacecraft, shielded by its gold-coated aluminum cover, thirty-thousandths of an inch thick. On this cover are not just the instructions on how to play the record but also how to reconstruct the pictures encoded on the record (using the vibrations of the record needle as proxies for the brightness of each digitally reconstructed pixel), and a map indicating where and when this message was launched (“Earth, 1977”). But what is the best means of conveying this information to beings who would not be likely, by

any stretch of the imagination, to understand human languages or conventions? This is where people like Frank Drake were indispensable. “Frank Drake is a bit like Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein rolled into one,” marvels Jon Lomberg.

Unlocking the Code.

Examples of some of the 116 images encoded onto the

Voyager

Golden Record.

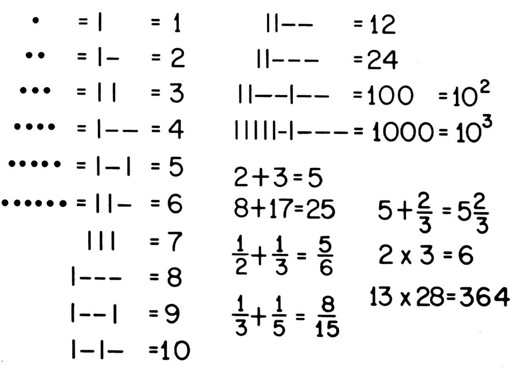

Image 3, defining the mathematical symbols and numbers used elsewhere among the images.

(Frank Drake)

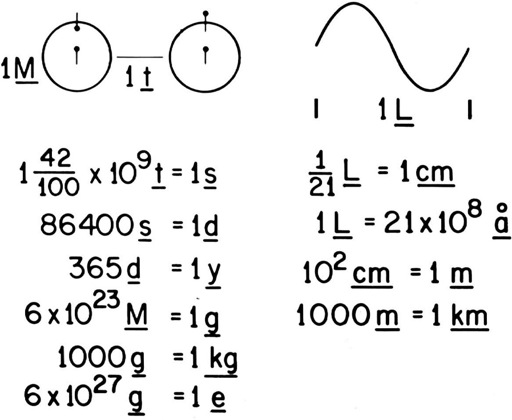

Image 4, providing a visual definition of the basic units of length, mass, and time used among the images, using the fundamental properties of hydrogen as the basis.

(Frank Drake)

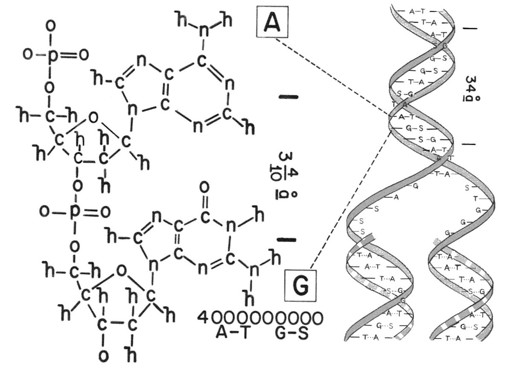

Image 15, showing the basic chemical and physical structure of DNA molecules, the building blocks of all life on Earth.

(Jon Lomberg)

Having been deeply involved in preparing earlier interstellar messages as part of the SETI program, as well as the plaques on the

Pioneer

spacecraft, Drake and others drew heavily from their past work. As on

Pioneer

, the location of our home planet in the solar system was indicated on the gold-anodized record case using a map whereby one can orient oneself using the location relative to a number of prominent pulsars—rapidly rotating neutron stars each with its own distinct frequency. And furthermore, since the frequency of these pulsars changes slightly over time, not only our

location

but

our

time

could be conveyed. But how would the pulsar frequencies be represented? That question led to another diagram etched on the cover of the

Voyager

record (also drawn from

Pioneer

): a diagram of the hydrogen atom (see figure on page 86).

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and it is rather simple—just one proton and one electron. The idea was to use the time it takes for the hydrogen atom to transition between its two lowest-energy states as the fundamental time scale (0.70 billionths of a second) and this would be the basis for how all other time would be indicated on the record. The pulsar frequencies could be represented in multiples of “hydrogen time.” Since hydrogen is so basic, it was assumed that intelligent life elsewhere would be able to decode this message. All numbers were represented in binary, a simple means of counting whereby all numbers can be represented by combinations of zeros and ones. So on the cover of the Golden Record, there is the pulsar map with frequencies represented in binary. The instructions for playing the record tell the user how fast to spin it (which happens to be 3.6 seconds per rotation, half the speed of what was then the standard for a 33

1

/

3

rpm vinyl LP) and also provide guidance on the more complex procedure of reconstructing the pictures, which must be traced with a series of interlacing vertical lines. As a sort of a test for anyone attempting to decode the pictures, below these instructions there appears a picture containing only a circle. This is the image that would appear if the first picture in the set were decoded properly. But if it came out as an oval, for example, instead of a circle, that would be an indication that something must be corrected in the decoding procedure. In this sense the circle was a calibration picture.

All of this was very clever, but who knows whether intelligent

life originating elsewhere in the galaxy would have the correct faculties to decode it. Sagan, Drake, Lomberg, and the other team members presumed that any aliens who found the record would understand atomic physics and recognize hydrogen as the universe’s most common element, and perhaps would also recognize other molecules as common (H

2

O, DNA?). They presumed that the aliens would use vision and hearing of some kind to reconstruct and understand the music and pictures, although one can imagine purely tactile ways to perceive the content as well. They presumed that the finders would have an understanding of deductive reasoning, of representations of time, and of the causality of events. Perhaps even the idea of pictures and music being used to tell a story would end up being truly alien to them, however. “

It’s wise to try every possible approach,” Frank Drake wrote in a recent interview, “because we’re not very good at psyching out what extraterrestrials might actually be doing.”

If the exercise were repeated today, perhaps we would include more sophisticated representations of physics, chemistry, astronomy, and biology, taking advantage of forty years of technological advances since the 1970s. Maybe Madonna or Michael Jackson or Lady Gaga would find their way into the recordings. Maybe we would find a way to capture more of the complexity and dichotomy of our species (being capable of both such beauty and such horrors) without necessarily appearing as threatening. Perhaps we would embrace more of the historical honesty and social introspection characteristic of our times by telling the finders, effectively, “Hey, check us out a little more if you can and make sure that you’re not going to be sorry you called.” A little of Hawking’s medicine might not be such a bad idea. If not, then perhaps at least today’s lawyers

would want us to plaster a big

CAVEAT EMPTOR

on the front casing to help stave off lawsuits in case we don’t meet alien expectations.

NASA did impose bureaucratic hurdles in the approval process for the contents of the record—Sagan’s cohort was not completely under the radar. For example, although the somewhat contentious cartoonlike drawings from

Pioneer

of nude humans were used once more on

Voyager

, an actual (tasteful) photograph of a nude pregnant woman and a nude man holding hands was left out for fear of an adverse public reaction.

In addition to NASA executive committee vetoes, in some cases copyright permission was denied or its pursuit simply abandoned. Because this record did not actually promise any sales, there was little incentive for any corporate entity, particularly a recording company, to accelerate the approval process. I asked Jon Lomberg if there was anything missing from the

Voyager

record for this kind of reason. “The Beatles,” he responded instantly. All four members of the band wanted “Here Comes the Sun” included—but their publisher wouldn’t grant the rights.

“In some ways the Beatles were the most obvious choice to include on the music. They were still at the peak of their fame, even though they’d broken up five years before. It would have been like putting on Shakespeare—who is going to seriously say that Shakespeare doesn’t belong among the greatest hits of Earth’s literature? The Beatles were sort of the absolute peak of Western musical achievement at the time. So that was a big disappointment. It made the suggestion of who to replace them with by no means obvious, because there was a whole tier of great musical performers. In the end, Tim Ferris’s choice of Chuck Berry was a good solution.”

Bill Nye recalls, “I was in class at Cornell in the spring of 1977

when Carl Sagan asked us which Chuck Berry song to put on the records. He actually pitched ‘Roll Over Beethoven,’ but we all insisted that the record include ‘Johnny B. Goode’ instead. And so it came to pass.” Passing the youth test, it apparently passed the social-media test of the day as well: Steve Martin did a skit on

Saturday Night Live

in spring 1978 where an alien’s response to the

Voyager

record was “Send more Chuck Berry!” “It is a sobering thought, though,” Jon Lomberg nonetheless laments, “that it was easier to send a record into deep space than it was to try to market it here on Earth.”

Drake, Lomberg, and the others searched through picture books in libraries, in magazines from

National Geographic

to

Sports Illustrated

, and in NASA’s photo services. When they couldn’t find a photo they were looking for, the picture group composed and shot some of their own. Six, in fact. Lomberg also devised a dozen original diagrams that contained important visual and other information. He would later go on to use his skills to create much of the graphic space art for Carl Sagan’s original 1980 television series,

Cosmos

. They worked hard to try to choose images that they expected would be the most informative and the least confusing. And they spent a lot of time playing extraterrestrial head games—trying to put themselves in the shoes (or whatever) of beings viewing the pictures without the benefit of the unconscious context that we all have by virtue of living on Planet Earth.