The Interstellar Age (9 page)

Read The Interstellar Age Online

Authors: Jim Bell

Pressure and stress levels mounted as changes were being made closer and closer to the deadline for uplinking the final imaging sequence to the spacecraft. To help relieve some of her own stress, and the team’s, Candy would bake cookies. “The later the change in the sequence, the more cookies I would bake for the sequence team to thank them for letting us make the

really

late changes,” she recalls. During the pressure-packed lead-up to each of

Voyager

’s planetary encounters, Candy was hardly ever at home. If she was, she was baking. . . .

Despite the many checks and double checks, by multiple people, “Mistakes still happened,” Candy says, “and you never forget them. Estimating exposure times was a big deal. For example, we were updating Neptune exposures in the last iteration of the sequence before it went to

Voyager 2

and I miscalculated the exposure times on two images. I was working with a specific science team member on the planning of these images, and I don’t think he ever forgave me . . . and here it is, twenty-five years later, and I still feel bad about that.”

But the vast majority of time, things went right. Linda Spilker,

another instrument scientist with

Voyager

, and now the JPL project scientist for the

Cassini

Saturn orbiter, recalled the personal rewards from seeing the process run well from end to end. “I found tremendous satisfaction in seeing the data from an observation that I had carefully planned with input from the IRIS team reach the ground and be carefully analyzed,” she says, referring to her role in planning observations from

Voyager

’s infrared radiometer interferometer and spectrometer instrument (IRIS). “What new revelations would that data contain about mighty Titan or intriguing Triton? My job was to carefully review each and every spacecraft command for every

Voyager

IRIS sequence and to make sure that those commands were right.” High pressure, for sure, but high rewards, too.

The kinds of job-related stresses that sequencers faced during the one-shot flyby missions of

Voyager

are somewhat different from the stresses faced by sequencers and their teammates operating orbital spacecraft, such as the

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

or the Saturn orbiter

Cassini

(both of which Candy is currently involved with), or landed missions like the Mars rovers that I have worked on. In those cases, if an exposure time is botched or some other sequence error occurs, it’s often (though not always) possible to take a “do-over” the next day, or the next orbit, to get it right. But still, in my experience and in the experience of almost everyone I know in the business, such mistakes are rare. The men and women tasked with doing the often thankless, almost anonymous, work of the nuts-and-bolts day-to-day care and feeding of spacecraft—including developing the detailed, step-by-step sequences that tell our far-flung robots exactly what to do—are among the most careful, thoughtful, conscientious, and trustworthy people I know. Dozens of people like Candy Hansen, Linda Spilker, and Suzy Dodd filled

such roles on

Voyager

. And they are only a subset of the many thousands of people that it typically takes to design, build, test, launch, and run a modern ship of exploration. Charley Kohlhase estimated that a total of 11,000 work years were devoted to the

Voyager

project through the Neptune encounter in 1989—equivalent to a third of the labor force needed to

complete the Great Pyramid at Giza for King Cheops.

Working closely in the trenches with science and engineering and management colleagues on a high-stakes, high-stress space mission is a bonding experience for such teams of people. I can imagine that the experience is perhaps comparable in some ways (though not life threatening!) to what it must feel like for a team of mountaineers to tackle a particularly dangerous and challenging peak together. You learn to rely on your teammates, to understand and respect the entire range of skills and capabilities that it took to get to the top, and to celebrate successes and mourn failures as the life-changing events that they are.

“It was a wonderful, wonderful, wonderful thing to be involved with,” Candy Hansen says, reflecting back on her

Voyager

years. “It was like working on a common cause, a common passion. You were working with people who really wanted the same goal, the same outcome.”

“We were young and fun!” recalls Suzy Dodd (who rose up through the ranks to eventually become the project manager of

Voyager

in 2010), while lamenting also, almost under her breath, “and now we’re old and gray. . . .”

When I asked Charley Kohlhase to try to pinpoint the glue that helped to bind the team together through all the years and the billions of miles traveled, he says the key was that “the

Voyager

team

had tremendous devotion to the job.” Perhaps

Voyager

sequencer Ann Harch, now a veteran of many more NASA missions over the past thirty years, summed it up best: “I can say without reservation that

Voyager

was the best-managed mission I ever worked on. The managers trusted their team chiefs and let them do their jobs. There was no micromanaging. Miracles happened with that kind of management. It truly was a magical mystery

ride!”

3

Message in a Bottle

D

URING THE LAST

few centuries, humans have shown a remarkable ability for decoding messages in languages or codes that they had never previously encountered. Linguists were able to decipher the Greek written language Linear B from about BCE 1450 without any ancient Greeks around to provide tips. During World War II, Cambridge mathematician Alan Turing and the Allied Forces were able to decipher the ingenious Enigma machine ciphers used by the Nazis to great effect in North Atlantic naval battles. It seemed reasonable, then, to assume in the 1970s that any form of intelligent alien life as smart or smarter than ourselves would be able to decipher a message we sent to them, no matter how rooted it was in our culture, solar system, and galactic address. After all, we would be trying to make ourselves understood.

But then, if you were given the chance to compose a message to the future, to some conceivable or even inconceivable intelligent life out there in our galaxy, what would it be? It is a harder problem than it might first appear. . . .

That was the precise opportunity that presented itself when a small group of visionaries realized that long after the completion of

Voyager

’s scientific mission, the two spacecraft would continue to travel on silently, headed on an irreversible course out of our solar system and into the uncharted vastness of space. When the trajectories for

Voyager 1

and

Voyager 2

were chosen early in the history of the project, their ultimate long-term fates were sealed: both spacecraft would be traveling so fast because of their gravitational slingshots past the giant planets that they would achieve escape velocity from the solar system. That is, they would no longer be in orbit around the sun, but instead would be on one-way trips to interstellar space, no longer bound to their parent star like the rest of us. The

Voyagers

would be emissaries—human artifacts, time capsules of a sort, technological snapshots of what our species and our civilization was capable of doing during the time when the spacecraft were built and launched. The idea of including a message in those bottles cast into the cosmic sea seemed appropriate.

But what message would be the right one to send? This weighty question would ultimately be pondered by a small group of scientists, writers, and artists led by Carl Sagan—a group who would also reach out for advice and input to a larger range of scientists, artists, philosophers, teachers, and dignitaries throughout the world. Could people rise to the challenge of crafting a unified message representing not their own parochial interests or agendas, but their

hopes, dreams, and experiences as citizens of Planet Earth? Sagan believed they could. The secretary-general of the United Nations at the time, Kurt Waldheim, proposed (unsolicited by anyone involved with

Voyager

) a moving letter as his contribution to the message, with the words, “

We step out of our Solar System into the universe seeking only peace and friendship, to teach if we are called upon, to be taught if we are fortunate.” With this and countless other words, music, and images that emerged from the challenge, Sagan and others would try to bottle our dreams and send them adrift with our aspirations, etching them into a golden time capsule known as the

Voyager

interstellar message.

Carl Sagan had been largely responsible for an interstellar message in the form of a plaque sent off with the NASA

Pioneer 10

and

Pioneer 11

spacecraft. The

Pioneers

were humanity’s first missions beyond Mars, the first to fly past Jupiter (in 1973 and 1974), the first to fly past Saturn (

Pioneer 11

in 1979), and the first human-made objects to be accelerated beyond the escape velocity of the sun. They were pathfinders for the follow-on

Voyager

missions, demonstrating many of the technologies and celestial navigation methods that would later prove critical to the

Voyagers’

successes; for example, demonstrating the use of gravity assist at Jupiter, and proving that spacecraft could pass unscathed through both the Main Asteroid Belt and the plane of Saturn’s rings. In addition, the

Pioneers

did some of the initial science scouting that would allow the

Voyager

science instruments to be optimized; for example, measuring the powerful radiation and magnetic-field levels at Jupiter and Saturn, and taking some of the first high-resolution images of those

planets.

Messages from

Pioneer

and

Voyager

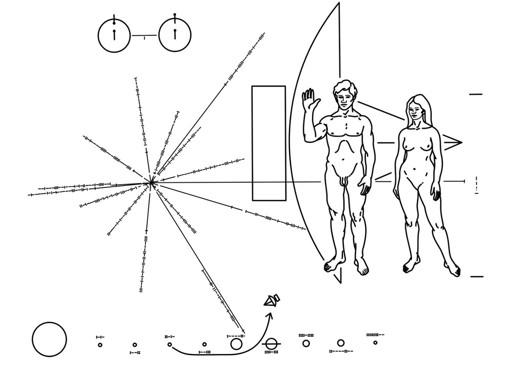

. Top:

Plaque designed by Sagan, Drake, and Salzman Sagan for the

Pioneer

missions.

(NASA/JPL)

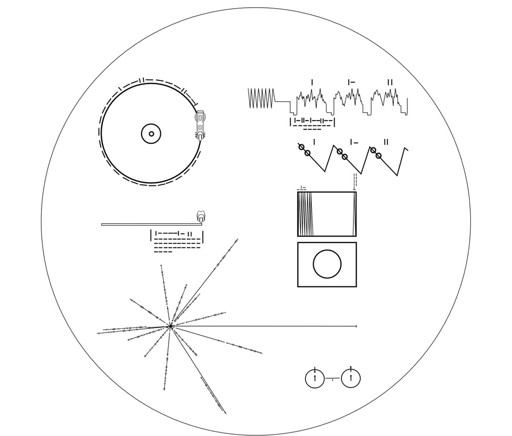

Middle:

Plaque designed by Sagan, Drake, Lomberg, and others for the

Voyager

missions, and engraved onto the cover of the

Voyager

Golden Record.

(NASA/JPL)

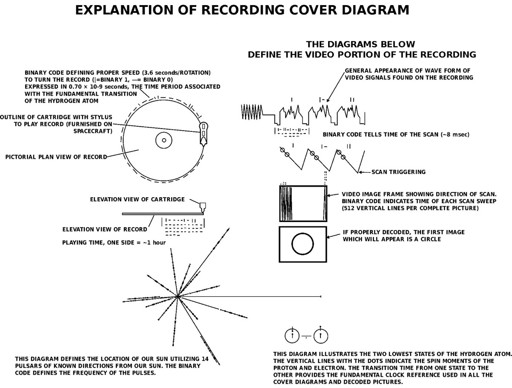

Bottom:

Explanation of the symbols and markings used on the

Voyager

plaque.

(NASA/JPL)

In the early 1970s, Sagan; his wife, the artist and writer Linda Salzman Sagan; and the pioneering Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) astronomer Frank Drake acted on the idea put forward by science journalist Eric Burgess and author Richard Hoagland that humanity shouldn’t miss the opportunity to include a message of some kind on these high-tech emissaries that were about to be

cast out forever into interstellar space. With access to

Pioneer

project officials for the technical details of the spacecraft

and to NASA headquarters officials for the required permissions, but with only three weeks to get the job done, Sagan, Salzman Sagan, and Drake came up with a clever gold-anodized aluminum plaque etched with rudimentary drawings and markings based on fundamental physics and astronomy, which they hoped would enable some comparably (or more) intelligent extraterrestrial species who might intercept the spacecraft in the far future to tell where and when it came from.