Read The Invitation-Only Zone Online

Authors: Robert S. Boynton

The Invitation-Only Zone (14 page)

Kojima unburdened himself to his old friend, confessing his doubts about the North Korean experiment, and perhaps about communism itself. He told Sato how carefully his every step in North Korea had been choreographed by his minders,

and how even the most seemingly innocent scenes were deemed inappropriate. He described the photos he had been forbidden from taking, and those that the censors had destroyed before he boarded his flight home. Had anyone other than Kojima said these things, Sato would have doubted him. But while watching the video footage, Sato began to realize that most of what he knew about North Korea was

a carefully curated lie. “From then on, every time I saw an official photograph or article, I sensed the level of fabrication that had produced it,” he says. “There was no relation to reality in what they were trying to feed us.” As the sun rose, the two men sat in silence. They thought about the thousands of people they had sent to North Korea. “Sure, you’ve read the word

tyranny

, but have you

ever really stared at tyranny itself? Have you seen concrete evidence that it exists, and known that you helped facilitate it?” asks Sato.

It took four years for Kojima to break with the party. He opened a kimono shop in northern Niigata, avoided his political friends, and tried to forget about the repatriation project. Sato had a more visceral reaction. A month after the night that Kojima showed

him the video footage of North Korea, he came down with a psychosomatic asthmatic illness that made breathing difficult, sometimes impossible. He’d awake in the middle of the night gasping for air. At first he feared his tuberculosis was back, but the doctors found no evidence of that.

In 1965, Sato and his family moved to Tokyo, where he found a job with the Korea Research Institute, a pro-North

Korea think tank that published policy papers about the peninsula. Working in a large city gave him access to a wider range of people and information than before, and he made the most of it, devouring anything having to do with North Korea. With his energy, Sato was soon running the institute. What’s more, his neurotic illness disappeared, and he was able to breathe freely. Though disillusioned

with North Korea, he still believed in the ideals of equality and justice he associated with the global Communist movement, and he refocused the institute to lobby for the rights of ethnic Koreans in Japan.

Sato visited China in 1975, during the final days of the Cultural Revolution, when Mao’s cult of personality thrived and all who opposed him were terrorized. Sato was startled to see evidence

of authoritarian tendencies similar to North Korea’s. Mao, like Stalin and Kim Il-sung, dominated every aspect of society. Here, finally, was proof that the problems with the North Korean experiment weren’t an aberration, but part of the DNA of communism itself. Sato’s loss of faith was comparable to the one he had experienced at the end of the war. “I had memorized the Marxist discourse so well

that I could pull it out and apply it to any situation. But now I had to refute all the ideas I had held as true, breaking down every theory. And then I had to build up my own sensibility from scratch, piece by piece. For the next three years I was barely able to write a sentence,” he says. Sato’s evolving ideology no longer fit with the Korea Research Institute’s pro-North Korea policies, and

in 1984 he broke with it and founded the Modern Korea Institute, starting a journal that became an important outlet for anti-North Korea essays and research. “I helped send the Korean residents in Japan to hell,” he wrote in a remorseful 1995 essay, “instead of to the paradise they were promised.”

11

NEIGHBORS IN THE INVITATION-ONLY ZONE

For all the regime’s security arrangements, information circulated within the Invitation-Only Zone via one of humankind’s most durable cultural practices: gossip. Soon after Kaoru and Yukiko moved into their first house, the woman who looked after them stopped by to introduce herself. The Hasuikes had not yet assumed their new identities and simply

told her where they were from. “Ah, so you’re Japanese!” the woman exclaimed, after hearing their accented Korean. “Another Japanese couple arrived a while ago. You should meet them!”

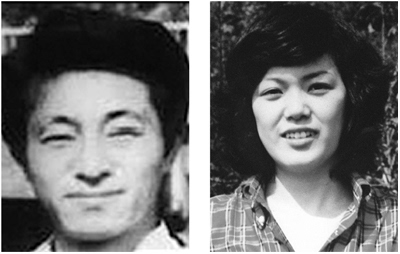

Engaged to be married in the fall of 1978, Yasushi Chimura and Fukie Hamamoto, both twenty-two, lived with their parents in Obama, a small coastal town three hundred miles west of Tokyo. Fukie sold cosmetics, and

Yasushi worked in construction, and when they wanted to be alone, they drove Yasushi’s car up a steep, twisty single-lane road to a cliffside park where couples came to gaze out at the ocean and kiss. July 7 was a moonless night, and Yasushi and Fukie were sitting on a bench, picking out the familiar lights from the blackness that had enveloped the town, when four men jumped out from behind nearby

bushes. After restraining the couple and placing them in separate bags, the men slung them over their shoulders and carried them several hundred feet down the hill to a waiting dinghy. As the men crossed the road from the bluff to the beach, Yasushi peered through the bag’s mesh material and caught a glimpse of a passing car’s taillights.

Young Yasushi and Fukie Chimura (Kyodo)

Like the Hasuikes, the Chimuras were separated before they arrived, each assured that the other had been left behind in Japan. Each morning when she awoke, Fukie would at first think she had only dreamed about the abduction. She yearned for Yasushi, whom she had expected to marry that fall. As weeks turned into months, and the reality of her situation

sank in, her mood shifted from absolute despair to a kind of grim determination. She had to survive her ordeal. “I can live here, if I have to. But please, God, don’t let me

die

here,” she thought to herself.

1

Fukie’s minder repeatedly inquired whether she had any interest in getting married, which she interpreted as a tease about being of a “marriageable age.” Gradually she realized he was serious,

and feared she’d be forced into an arranged marriage, perhaps with a North Korean spy. “I knew I didn’t want to marry anyone from North Korea, so I just replied as if it were a big joke. I’d say ‘Are you

kidding

me? I couldn’t do anything like that.’” So she had good reason to be apprehensive on the day she was presented with a pretty new dress and ushered into a suite of rooms that had been decorated

for a formal occasion. An arranged marriage was indeed on the agenda, but the groom was familiar to her. After eighteen months of study and despair, Yasushi and Fukie wed the same day they were reunited.

Given that everyone living in the Invitation-Only Zone had secrets to hide, neighbors tended to keep their distance. It turned out that Kaoru and Yasushi had actually met during their first few

months in captivity, but each had avoided discussing his circumstances for fear that the other was a spy planted to test his loyalty. In the Invitation-Only Zone, the two couples lived a few houses from each other. In order to talk privately, Kaoru and Yasushi developed a schedule for secret get-togethers, usually meeting at a designated spot in the surrounding woods. At the end of each meeting,

they’d set a time, date, and place for the next one. They grew close, almost like brothers, and looked forward to talking, if only for the opportunity to compare notes and commiserate. Yasushi, a high school dropout, was impressed by Kaoru’s intelligence and often turned to him for advice. After the birth of their children—the Hasuikes had a son and a daughter; the Chimuras, two sons and a daughter—the

families would get together regularly for birthdays and holidays. There were times when, amid the pleasant excitement of friends and food, Kaoru would look out over the two families and momentarily forget where he was.

* * *

By paying the abductees for their work, as it would any other citizen, the regime perpetuated the myth that they were in North Korea under normal circumstances. Although

heavily regulated, certain markets were allowed in the North, even though the regime occasionally issued currency reforms and took other measures to curtail the freedom that came from exercising economic power. Paying the abductees in North Korean won would have been risky because it would have given them too much freedom to shop wherever they liked. So, initially, abductees were paid in a kind

of government-issued scrip that could be used at only one store, the better to keep track of them.

During the later part of their captivity, the abductees were paid in American dollars. The official dollar-won exchange rate was absurdly low, fixed at the symbolically significant ratio of 2.16 North Korean won per U.S. dollar. (February 16 was Kim Jong-il’s birthday.) One day, one of the chauffeurs

offered to change Kaoru’s dollars into won on the black market. He received a better rate and could therefore frequent inexpensive local merchants rather than only the designated foreign currency stores, where prices were several times higher. In the upside-down world Kaoru and the others inhabited, Japanese abductees posing as North Korean citizens were now able to exchange American dollars

for North Korean won in order to purchase European toiletries.

Traveling outside the Invitation-Only Zone was permitted but was regulated by procedure. Fukie tried to leave the zone as often as possible. It was a change of scenery, a chance to buy some of the items she, a professional cosmetologist, missed from Japan. She usually shopped at the duty-free shop in downtown Pyongyang, using her

government per diem to buy sweaters, cotton underwear, and a particular brand of French shampoo she was fond of. For her minder, however, every foray outside the zone was a potential security breach. A routine developed. Fukie’s minder would pick her up at her home in an unmarked sedan and drive forty-five minutes to downtown Pyongyang. As their car approached the duty-free store, he would scan the

license plates of the cars parked out front. North Korean license plates are color-coded—the license plates of foreign diplomats are blue, military plates are black, and the few people wealthy enough to own private cars have orange plates—so that the provenance of every vehicle can be identified from a distance. If he spotted a foreigner’s plate, Fukie’s minder would circle the block until the suspicious

car left.

Oddly, once inside the shop, Fukie’s minder didn’t pay much attention to the people she encountered there. In fact, she suspects there were times when he intentionally arranged for her to come into contact with foreigners, just to see how she behaved. In addition to Pyongyang’s few tourists and diplomatic staffers, Fukie met a virtual United Nations of abductees—from Italy, Thailand,

Romania, and Lebanon. Always cautious, she would glance at her minder before initiating contact. “As long as I didn’t talk to any Japanese people, I don’t think he cared whom I met. After all, what could any of us do?” she says. Conversations were always circumspect, and nobody said a word about

how

they’d come to be living in North Korea. The abductees would swap items among themselves, trading

shampoo for cosmetics and other goods, before getting back into their respective cars and returning to their own Invitation-Only Zones.

* * *

Having children tied Kaoru and Yukiko more firmly to life in North Korea. The couple gave their son and daughter secret Japanese names, Shigeyo and Katsuya, when they were born in 1981 and 1985. Kaoru had lost interest in his own life, but with children

he now felt a sense of hope for the future. “I lost my family bonds due to the abduction, but was now able to create new bonds,” he says. “To ensure that our kids could eat, have their own families, and live a life worth living after we died—that became the goal of my life,” he explains. “Dreaming about their future made our lives more bearable.” North Korea was his children’s home in a way

that it had never been his, and he had to do whatever he could to help them survive.

2

Kim Jong-il’s first public appearance, in October 1980, gave Kaoru cause for hope. The aging Kim Il-sung had been making arrangements for his son to succeed him since the late 1960s, and while newspapers had mentioned Kim Jong-il before (as when he joined the Politburo in 1974), his image had never appeared

in public. “He represented a brand-new hope for us. A strong, young man who would lead the country into a new era,” Kaoru recalls. “There was a great deal of excitement throughout the country, and I shared it.” In addition to introducing Kim Il-sung’s successor, the Sixth Congress of the Workers’ Party kicked off a new seven-year economic plan, at the end of which every citizen was promised a color

television, new clothes, and improved housing. “We were promised a new era with a very specific description of what that would entail,” Kaoru says.

If he and Yukiko were confined to a bubble, their children lived in a bubble within the bubble. Every day, a minder would ferry the Hasuikes’ son and daughter back and forth to daycare facilities outside the Invitation-Only Zone. Like kids growing

up anywhere, the children perceived their lives as normal. For native North Koreans, secrets and omnipresent surveillance were as common as air. To them, the Invitation-Only Zone was not a prison, but rather the North Korean version of a gated community.