The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923 (22 page)

Read The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923 Online

Authors: Marie Coleman

Tags: #History, #General, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #Ireland, #Great Britain

One event that has recently highlighted the controversy about sectarianism during the War of Independence was the botched execution of Richard and Abraham Pearson, members of a small Protestant sect known as Cooneyites, in Coolacrease, near Cadamstown in County Offaly a few days before the truce. Defenders of the IRA claim the Pearsons were spies and informers who deliberately antagonised and threatened the IRA and the local civilian population and that some of the girls in the family socialised with British soldiers. It has also been suggested that the local jealousy of the Pearsons’ large farm, dissatisfaction with their compliance with a government compulsory tillage order during the First World War, the desire of the hitherto inactive Offaly Brigade to record a success before the truce and the perception of the Pearsons as an alien element within the community were factors responsible for their deaths (Hanley, 2008: 5–6).

The Bureau of Military History witness statements (see Chapter 2) provide detailed accounts of the War of Independence from the perspective of the participants.

The only single-volume history of the war is Michael Hopkinson's,

The Irish War of Independence

(Gill and Macmillan, 2002). Studies of the war at regional level are quite plentiful and include Joost Augusteijn's,

From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare: The Experience of Ordinary Volunteers in the Irish War of Independence, 1916–1921

(Irish Academic Press, 1996), Marie Coleman's,

County Longford and the Irish Revolution, 1910–1923

(Irish Academic Press, 2003), David Fitzpatrick's pioneering study of County Clare,

Politics and Irish Life: Provincial Experience of War and Revolution

(Gill and Macmillan, 1977), Peter Hart's,

The IRA and Its Enemies: Violence and Community in Cork, 1916– 1923

(Oxford University Press, 1998) and John O’Callaghan's,

Revolutionary Limerick: The Republican Campaign for Independence, Limerick, 1913–1921

(Irish Academic Press, 2010).

The nature of the IRA's guerrilla campaign and the British response to it are the subject of Charles Townshend's,

The British Campaign in Ireland, 1919–1921: The Development of Political and Military Policies

(Oxford University Press, 1975) and

Political Violence in Ireland: Government and Resistance since 1848

(Oxford University Press, 1984). The British security response is also considered in D. M. Leeson's,

The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence

(Oxford University Press, 2011).

Plate 1 John Redmond delivering a speech on the third home rule bill, April 1912.

(© Getty)

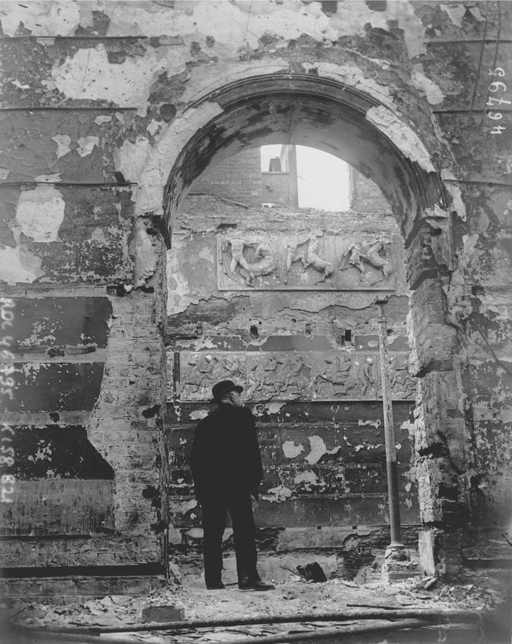

Plate 2 The destruction of the GPO after the Easter Rising, 1916.

(© Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Plate 3 The Irish Citizen Army outside Liberty Hall.

(© Getty)

Plate 4 Arthur Griffith (1871–1922).

(© National Library of Ireland)

Plate 5 Eamon de Valera (1882–1975).

(© National Library of Ireland)

Plate 6 Constance Markievicz (1868–1927).

(© National Library of Ireland)

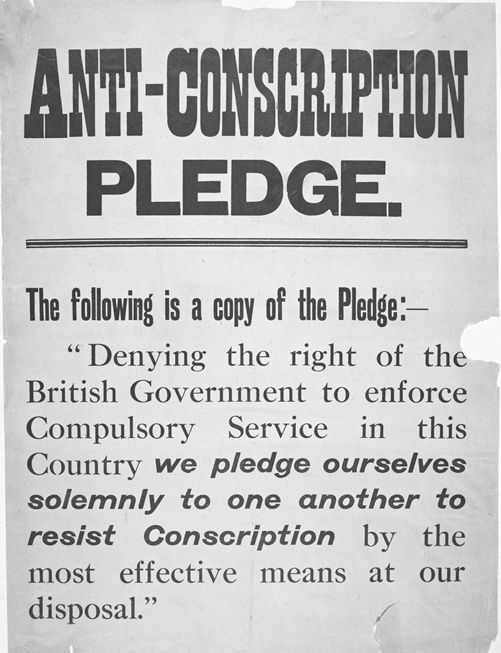

Plate 7 Anti-conscription pledge poster.

(© National Library of Ireland)

Plate 8 Auxiliary recruits.

(© Getty)

Plate 9 The Irish Army taking over Portobello Barracks, Dublin, in 1922.

(© Getty)

Plate 10 Sir James Craig, first prime minister of Northern Ireland at the opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament in City Hall, Belfast, June 1922.

(© Getty)

BRITISH POLICY IN IRELAND, 1919–21

T

he two tasks facing the British Government in regard to Ireland during the years 1919–21 were restoring law and order and finding a political settlement. The Government of Ireland Act had been postponed for the duration of the First World War and was due to be implemented. Events in Ireland in the meantime meant that it could not be enforced in the form it had taken in 1914, so the government was tasked with drawing up yet another home rule bill for Ireland.

The government's ability to deal with the IRA insurgency was hampered by poor leadership. The Irish administration based in Dublin Castle was unprepared for dealing with the IRA's guerrilla campaign and Sinn Féin's usurpation of the powers of the state. The Lord Lieutenant for most of the period was the retired Field Marshal, Lord French, who was chosen because of his Irish family background and support for home rule. However, he was unsuitable for the circumstances that prevailed in Ireland during the War of Independence. He was neither a good administrator nor politician and fell too heavily under the sway of prominent unionists such as Walter Long. He failed to take republicans seriously and, as a former soldier, advocated suppression of the guerrilla campaign. His position was not helped by the role of his sister, Charlotte Despard, in the republican movement.