The Italian Boy (11 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Not every metropolitan parish was as fortunate in its constables, however. In St. Pancras, eighteen rival watch trusts divided up the policing of the parish without any common system; Lambeth, Fulham, and Wandsworth were said to have no night watchmen at all, while at one point Kensington was said to have had just three parish constables. If a parish constable saw a crime taking place on the other side of the street and that other side was in another parish, he was unable to intervene.

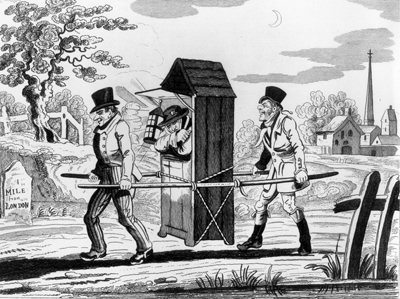

A Charley is removed far from his place of watch as he dozes, in this unsigned engraving of 1825.

This “old” system of policing—much of it dating back to Tudor times—was generally perceived as inadequate to the needs of modern society, as well as inherently corruptible: in 1816, six Runners had been transported after having been found guilty of setting up robberies. It was to change this system that Robert Peel, home secretary in Wellington’s premiership, devised his Metropolitan Police Act in 1829. The act proposed a single, unified police force for London that would be uniformed (a controversial innovation) and under the command of two government-appointed commissioners: this, too, was inflammatory, because it made central government—rather than the London parishes and the local magistrates at London’s nine police offices—responsible and answerable for policing. Hostility was also expressed toward attempts to put any Englishman under state surveillance—a distinctly foreign concept, it was believed, that would imperil the freedom of the individual. There were fears that Peel’s New Police would be a militaristic body, placing the country at the mercy of thousands of uniformed petty despots, acting as they wished with full governmental backing.

Faced with such strong opposition, Wellington’s government passed a watered-down version of Peel’s bill, excluding the City of London; the City (the “Square Mile” enclave within Greater London bordered by Whitechapel to the east, Holborn to the west, the rundown district of St. Luke’s, Old Street, to the north, and the river Thames to the south) was permitted to continue with its own ancient method of policing. This meant that areas within the City boundary, such as Smithfield, the Bank of England, St. Paul’s, Fleet Street, and Barbican, retained their chaotic Charleys-plus-parish-watchmen system, overseen by the similarly antiquated government of the City—the court of aldermen and the Corporation of London. The rest of London, lying outside the City, was divided by the first Metropolitan Police commissioners into seventeen divisions, covering an area of about twelve miles radiating from Charing Cross: Whitehall was A Division, Westminster was B, St. James’s C, Marylebone D, Holborn E, and so on. Each division was headed by a superintendent (Joseph Sadler Thomas was the superintendent of F Division—Covent Garden) and comprised eight sections, each section consisting of eight “beats” worked by ten men (one sergeant and nine constables). A beat was one to one and a half miles long—an officer was to be able to see each part of his beat every quarter of an hour or so, walking at around two and a half miles an hour. This pattern was superimposed on the parochial geography of London, cutting right across old parish boundaries.

On the morning of Saturday, 26 September 1829, almost one thousand men (some two thousand had applied for the positions) lined up on the grounds of the Foundling Hospital, near Gray’s Inn Road, to be sworn in as London’s first New Police officers and were issued their blue uniforms and equipment—their only weaponry was a short wooden stave, or baton. From the moment of their formation the Metropolitan Police encountered tremendous resistance. Contempt for Peel’s Bloody Gang, Peel’s Private Army, the Blue Devils, the Plague of Blue Locusts permeated the whole of London society. The antipathy was as deeply felt in the drawing rooms of the West End as it was in the capital’s “flash houses”—pubs and taverns where stolen goods were fenced and new robberies plotted. Many among the middle classes wondered whether the arrival of the New Police was simply the first in a line of measures to restrict an Englishman’s liberty; even an Englishwoman’s liberty was at risk. This letter to the

Times

was a characteristic response:

Sir, I see by your paper that a few days since [magistrate] Mr Roe, of Great Marlborough Street, committed some dozen women of the town for not obeying the policemen when desired to leave the [Regent Street] Quadrant. I have observed lately various instances of the same illegal and arbitrary conduct. I am no patroniser of disorderly persons of any class or description, but if our personal liberty is of any value, and is not to be at the mercy of every insolent policeman, I should wish to know by what legal authority this very constitutional force assumes to itself the power of seizing and imprisoning any woman, disorderly or not, who does not choose to leave the streets at their command. I should also wish to be informed under what authority that excellent magistrate Mr Roe commits women of the town by wholesale upon the bare assertion (not oath) of the constable that the said women were disorderly, when it is well known that punishment is not inflicted for any act of disorder but for presuming to remain in the streets contrary to the prohibition of the policeman.

Let a law be passed that these unfortunate persons are not to be permitted to walk the streets at all and then they will at least be acquainted with the laws to which they are subject; but at present the law stands thus, “that any prostitute being found in the streets in a state of drunkenness, or acting otherwise in a disorderly manner, may be committed” &c. It is, therefore, clearly contrary to law to seize or imprison them for any thing short of this.

16

Many property owners and tradesmen were angered by the imposition of a centralized body over a set of local men—no matter how corruptly these may have been elected. On a more mundane level, parish authorities resented the new police levy that was imposed in place of the old watch rate, or tax, which had brought the additional benefit of keeping old men in employment and thus off the parish poor rate; some London parishes withheld their police-rate payments for as long as possible. Even Whitehall proved obstructive: when Melbourne took over from Robert Peel as home secretary in the new government of Earl Grey in November 1830, he tended to side with chief London magistrate Sir Richard Birnie (who once stated, “I never saw a constable who was perfectly competent”) in his relentless criticisms of the Metropolitan Police’s first joint commissioners, Charles Rowan and Richard Mayne. Rowan and Mayne, meanwhile, spilt a great deal of ink mollifying newspaper editors, refuting the notion that there was to be any increase in the numbers of Metropolitan Police officers.

17

George IV himself made a point of very loudly praising the manager of the Drury Lane Theatre in Covent Garden after a performance for refusing to allow any New Police into the building. The Runners were to retain their exclusive role of keeping an eye on pickpockets within the theater for ten more years.

18

The New Police were supposed to differ from their precedessors in practice as well as in structure. Members of the new force were to be drawn from the “respectable” sections of the working class: an ingenious stroke—using the poor to police the poor. Rowan and Mayne explicitly advised recruits to the New Police against cultivating informers and mixing with villains, and officers were expressly forbidden to enter the pubs and lodging houses in which thieves were said to meet. So the Runners were kept on in their capacity of infiltrating the underworld of thieves and receivers. In a sense, they were containing crime, by keeping a close eye on the most likely offenders and the premises where such people congregated. However, the much-loathed figure of the “common informer” continued to play a significant part in policing and securing convictions in the 1830s; indeed, this role had broadened during the eighteenth century to become crucial to the detection and prosecution of criminals. Every trial had to have a prosecutor. In trials for murder and manslaughter, rex or regina played the part—these crimes were deemed to have been committed against the Crown of England; but property crimes required a private prosecutor, and the real victim of the loss was often unable (through poverty or lack of free time) or unwilling to institute proceedings. In those instances, the informer would mount the case against a suspected thief and fill the role of prosecutor in the courts; upon a conviction, a portion of the value of the goods stolen was passed to the informer as a reward. In addition, an informer who brought to the attention of the authorities any citizen who committed a broad range of nuisances—shortchanging, food adulteration, the dumping of refuse in the highway, Customs and Excise abuses, for example—received cash payments. So unpopular was this role that an act of Parliament was passed specifically to outlaw physical attacks on informers. (An informer did not have to be a professional snitch, though. Not only were members of the public entitled to tell tales but they were often paid when they did—just one way in which the community was deemed capable of policing itself. However, juries were known to take into consideration the fact that “information received” had often been paid for and could choose to treat such evidence with skepticism.)

By contrast, there were to be no rewards for a Metropolitan Police officer who solved a crime or returned stolen goods to their rightful owner, and no justice-evading out-of-court deals were to be done by the new force. But if an officer was not close to the source of the criminality—mingling with thieves, fences, procurers, swindlers, and forgers; keeping the channels open between himself and the common informers—how could he realistically find out what he needed to know? If, as it seemed at the time, criminals were becoming increasingly well organized, what strategies could be put in place to discover their networks and thwart their plots?

The age of the detective as hero was imminent; in 1841 Edgar Allan Poe would introduce the sleuth to English-language fiction with Auguste Dupin in

The Murders in the Rue Morgue

. But in 1831, detection was a phenomenon as new and experimental as railway travel, gallstone removal, the omnibus, phrenology, Catholics in Parliament, the concept of votes for all. The notion of one man exploring the mechanisms and milieu of urban crime had been introduced to London in 1828 with the publication of the English translation of the memoirs of Eugène-François Vidocq (1775–1857), a criminal turned informer who went on to head Napoleon’s police department. Ghostwritten and unreliable, Vidocq’s

Mémoires

nevertheless enjoyed huge success in Britain and reached poorer homes through stage adaptations and plagiarisms. Vidocq’s appeal was that he could penetrate seemingly alien strata of urban society, bring back tales of the habits of these worlds, and provide solutions to crimes and mysteries.

19

That was the sort of man it would take to crack the Italian Boy case, since none of those in the know was talking.

Joseph Sadler Thomas was, in many ways, the model of the new type of policeman—but could he also be a London Vidocq? Although the New Police were a nondetective force, Thomas seems to have been keen to act the sleuth. Known for his zeal, he was already something of a local legend when he became the first superintendent of Covent Garden’s Division F at its formation in September 1829. But if “zealous” could have been his middle name, so too could histrionic, lachrymose, prudish, self-pitying, and outspoken. Since October 1827, Thomas had been the parish constable (that is, one of the “old” police) of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden—an unpaid post that he combined with his paid job as cashier at the box office of Covent Garden Theatre. Thomas’s aim, he told the Parliamentary Select Committee convened in 1828 to explore the parlous state of the police in London, was “to correct the many evils with which my neighbourhood abounds.… In consequence of my interference, I have reason to believe that a very great change has taken place for the better.”

20

Thomas’s opinions (“I perceived, as anybody else does, a wonderful apathy in the police officers”)

21

and activities (applying to magistrates to have cab stands removed, coffee stalls shut down, pub-license applications denied) had made him many enemies. His high arrest rate, which cast doubt on the competence of other officers, infuriated his Bow Street rivals. Thomas received threats of harm to his wife and three children, and once he was physically assaulted and dragged through the streets by two Runners and two officers of the Bow Street Day Patrol who, tired of his criticism of their indolence, decided to arrest him for loitering outside Drury Lane Theatre. “I was struck and dragged through the streets like a felon … past an exulting set of blackguards,” he told the 1828 Police Select Committee. Magistrate Sir Richard Birnie dismissed the charge of loitering that the Runners and Day Patrol had brought against Thomas; but many other London magistrates had little patience with him.