The Italian Boy (39 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

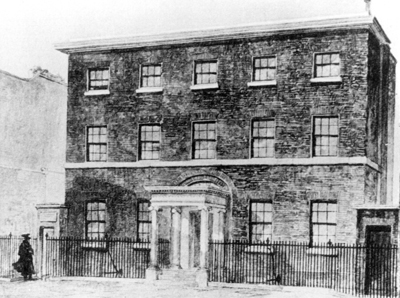

Head/Williams was dissected at the Great Windmill Street School of Anatomy, founded by William Hunter in 1768; the building still stands, as part of the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue.

It was with some confidence that phrenologist Dr. John Elliotson stated, on examining plaster casts of Bishop’s and Williams’s skulls, that “Bishop had got ideality, and no reflection,” while with Williams “the portion devoted to the animal propensities—the lower posterior and the lower lateral parts, especially destructiveness, acquisitiveness, secretiveness—is immense.” Williams’s head was “by far the worse,” claimed Elliotson: it was clear that Williams’s Combativeness was Very Large and his Veneration Very Small, while his Esteem was Full and his Love of Approbation Large. No wonder his life had been low and villainous, since he had been deficient in the “sense of what is refined and exquisite in nature and art.”

5

The early 1830s were the high noon of phrenology, and celebrated murderers such as Bishop and Williams were the most sought-after theory-proving material there was. What relation did the shape and size of the skull have to the mind that it contained? Were morality and intellect revealed in human tissue such as the scalp or the brain? What functions could be deduced from the way an organ looked? Sadism knew no social class, according to Dr. Joseph Gall (1757–1828), one of phrenology’s pioneers; Gall took pains to demonstrate—anecdotally—that the propensity for murder was as likely to be found in the wealthy lover of the arts as in the poorest peasant. He cited Nero, Henry VIII, a senior member of the Dutch clergy, and a count at the court of Louis XV as particularly depraved (though he never did see their heads).

6

It would be interesting to know what phrenologists would have made of the plaster casts of Bishop’s and Williams’s heads if these had turned up with no history attached; as it was, the craniometrists knew in great detail the deeds of the men whose skulls they were measuring. Elliotson’s report interweaves his analysis of Williams’s head shape with regurgitated background details about Williams’s life that were taken straight from the newspapers. Alas, Elliotson’s favored plaster-cast maker, a Cockney called Deville, had omitted to shave the entire scalps, which rather compromised Elliotson’s assessment of Bishop’s moral faculties, since matted hair had rendered this particular bump bigger than it really was.

Bishop’s head was smaller than Williams’s, which, deduced Elliotson, “agrees with the fact” that it was Williams who had first suggested the burkings (that was what had been reported, at least); and Bishop’s enlarged organ of Acquisitiveness tallied with his history as a paid informer and perjurer—more details gleaned from the papers. What we were to learn from these casts, said Elliotson, was that we should be grateful not to possess such terrible “organisation” of faculties and that it was our duty to encourage virtue and to ensure a steady supply of legally obtained corpses to anatomists, thereby removing the cause of Bishop and Williams’s crimes. These two men might even, he said, have made decent, if disagreeable, Christians, if murder hadn’t come so easily into their lives.

Elliotson tabulated his findings, just to make matters entirely clear:

| | BISHOP | | WILLIAMS |

Amativeness [sex drive] Philoprogenitiveness | | Very Large | | Large |

[Fertility; will to reproduce] Inhabitiveness | | Moderate | | Large |

[Urge to settle in one place] | | Moderate | | Moderate |

Adhesiveness [Tenacity] | | Large | | Moderate |

Combativeness | | Very Large | | Small |

Constructiveness | | Small | | Moderate |

Acquisitiveness | | Very Large | | Very Large |

Destructiveness | | Very Large | | Large |

Secretiveness | | Very Large | | Large |

Self-esteem | | Full | | Large |

Love of approbation | | Large | | Full |

Cautiousness | | Very Large | | Moderate |

Benevolence | | Very Small | | Small |

Veneration | | Very Small | | Moderate |

Hope | | Very Small | | Small |

Conscientiousness | | Very Small | | Very Small |

Ideality | | Small | | Small |

Firmness | | Small | | Small |

Knowing faculties | | Large | | Large |

Intellectual faculties | | Small | | Very Small |

The opponents of “bumpology,” as they called it, claimed that there was no relation between cranium and brain and that misshapen skulls were the result of a number of perfectly mundane factors, such as a blow to the head or tight-fitting headwear for children. Much muck was raked in the battle of phrenology, with one often-repeated anecdote (never sourced) about a trainee of Gall’s who had disinterred his own mother to prove a point.

7

Phrenology, though, was not a phenomenon that could be proved or disproved by advances in anatomy. Looking at dead matter, however brilliantly dissected, would not reveal how a brain, or brain faculties, worked. The soul, or spirit, could not be located, nor did there seem to be a way of demonstrating that it was merely the product of the nervous system. Discovering the essence of humankind—of life—was eluding those who wielded the scalpel.

While phrenology would decline into a parlor game by the 1860s, physiognomy—the observation and categorization of facial rather than cranial features—emerged into greater respectability as the nineteenth century wore on. It appeared to gain validity from the pioneering work of physiologists such as Herbert Mayo, Charles Bell, and vivisectionist François Magendie, who all helped to reveal the mysteries of facial muscle movement. Physiognomy had formerly been an illegal practice in England, undertaken by itinerant showmen who, in addition to reading “character” and future prospects from the faces of the credulous, might offer palm reading and the divination of omens, activities also outlawed by Puritans in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—and still illegal under the 1824 Vagrancy Act; but physiognomy was proving irresistible to the new society that was busy segregating itself into mutually exclusive groups. Anxiety about social flux could be allayed by typologizing and categorizing, and the need to feel certain about the “types” one was living among is likely to have been the driving force that made physiognomy increasingly prescriptive rather than merely descriptive, and nowhere more so than in the analysis of criminality. Thieves and prostitutes were said to know how to wear a “mask of decorum” by the late 1820s, where less than twenty years before, they had made little attempt to disguise who they were or what they did.

8

Beggars could be as adept as Drury Lane actors in striking poses, adopting airs, drumming up pathos. The city dweller was becoming his or her own work of art; self-consciousness and self-presentation were becoming key.

But like phrenology, physiognomy was not innocent of eye; visual data were used to prove points already decided by other types of evidence. So Thomas Williams was described, after his death, as having a “coarse and vulgar physiognomy,… a low, designing brow, a harsh severity of features.”

9

But before the guilty verdict, it was the very ordinariness of the prisoners’ appearance that had been commented on. At that point, the worst that had been said of any of the three was that Williams looked “cunning” (

Times

), though the same newspaper had also claimed that he looked “inoffensive—simple even,” while Bishop had never appeared worse than “sullen.” Yet a week after the executions, having viewed the sketches of the Bow Street and Old Bailey hearings published by printer Charles Tilt, the

Times

decided: “May looks more stupid, perhaps, than vicious, and yet his countenance is extremely revolting. The face of Williams exhibits the same attempt at disguise as is apparent in his costume, and an equal failure attends both: the metropolitan blackguard is not concealed by the countryman’s smock frock, and the brutality of his nature breaks through the affected sheepishness which he put on for the occasion. Bishop is rather more like a hog than a human being, and there is no attempt on his part to soften the harsh character with which Nature has branded him.”

10

Except that it was Bishop who wore the smock frock, not Williams—the picture had been wrongly labeled by Tilt.

But as late as 1883, plaster casts of Bishop’s and Williams’s heads were being advertised as “suitable for public or private museums, literary or scientific institutions,” along with the heads of Oliver Cromwell, “the Idiot of Amsterdam,” Coleridge, Sir Isaac Newton, William Palmer the Poisoner, and the five idiot progeny of one Mrs. Hillings; they cost a mere five shillings each, or forty shillings for a dozen.

11

* * *

No death portrait

had ever been circulated of the dead child of King’s College, and so the publishers of broadsheets and ballads were free to make up their own minds about how the victim of the Bethnal Green Tragedy might have looked. London was in love with its Poor Italian Boy, and he was memorialized in many catchpenny prints—often as a corpulent little chap with an insipid grin beneath a hugely exaggerated furry cap—while doggerel poured from hack poets’ pens. “The Italian Savoyard Boy,” for example, by one F. W. N. Bayly, appeared in the

Weekly Dispatch:

Poor child of Venice! He had left

A land of love and sun for this;

In one brief day of tears bereft,

Of father’s care and mother’s kiss!

The valleys of his native home,

The mountain paths of light and flow’rs;