The Italian Boy (38 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Dr. Cotton says that he understands the men wish to receive the sacraments, but Dr. Williams tells him that this won’t be necessary—the prisoners have changed their minds. Dr. Cotton says that he hopes that they have spent the night asking for God’s mercy. “Now gentlemen,” says Cotton to the interloping churchmen, “you’d better take your man, and retire to different parts of the room, where you can talk without interrupting each other.” Dr. Whitworth Russell takes Thomas Williams to the farthest end of the room, where they are seen speaking earnestly; Dr. Theodore Williams sits with Bishop close to the blazing fire. Cotton doesn’t like the approach to Christianity that these two churchmen are displaying and he approaches each of the two-man huddles and says, “Now gentlemen, time is hastening. Suppose you let them go and pray to God. You go there,” he says to Bishop, pointing to a bench near the window of the press room, “and you kneel down there,” he tells Thomas Williams, indicating a spot near the sink where crockery can be rinsed, “and pray heartily to God to forgive you your sins and have mercy on your souls through your Redeemer.” They do as they are told, and as they are praying Cotton is heard to remark, “Now this is a blessed sight.”

When they return to the bench near the fireside, Cotton asks them if they would like a little wine. They say yes, and Bishop downs one teacupful, but Williams is shaking and crying so much he is given a little more. Drs. Williams and Whitworth Russell have rejoined them and have started to discuss the crimes once again, and then they begin to advise them on how they should approach their imminent death, at which point Cotton says, “I will give those directions, if you please. All matters of that kind had better be left to me.”

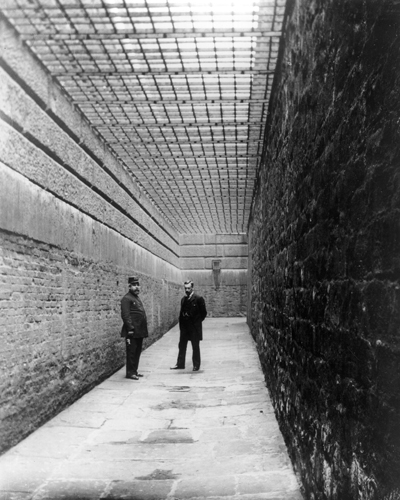

St. Paul’s can be heard striking eight. Bishop stands and says, “I am ready” and Cotton starts reciting the funeral service as Bishop and Williams, the sheriffs, undersheriffs, clergymen, and visitors rise and begin the walk to the scaffold. They descend into the subterranean Dead Man’s Walk, as Cotton reads, with the remains of the executed lying under the slabs they walk on, and then up into the small entrance hall behind Debtors Door, up a flight of stairs and through the prison’s bread room and the soup room, from which rise the stairs that lead directly to the gallows. They are opposite the King of Denmark. Bishop walks steadily, slowly, to the foot of the steps, but Williams becomes even more frenzied in appearance and begs to see Whitworth Russell once again. As Bishop moves out onto the platform, the chaplain of Millbank Penitentiary comes alongside Williams, sitting on a bench in the soup room, and their conversation is at first inaudible, but now, with Williams clasping Whitworth Russell’s hand as he moves onto the stairs to the scaffold, the condemned man is heard saying: “I hope God will have mercy upon me.” Whitworth Russell says that since Williams seems genuinely penitent, God is likely to be merciful. “Then I am ready to die. I know I deserve it, for other crimes I have done.” Whitworth Russell says, “You have just another moment between this and death, and as a dying man I implore you, in God’s name, to tell the truth. Have you told me the whole truth?”

Deadman’s Walk, the subterranean passage that led from the prison to the scaffold at Debtors Door

“All I have told you is true.” He won’t let go of the chaplain’s hands.

“But have you told me all?”

Williams hesitates, then says, “All I have told you is quite true.”

The crowd has spotted the executioner, William Calcraft, and his assistant on the scaffold and a cry of “Hats off!” is shouted among the thousands there: you get a better view with hats off. Silence falls. But the moment Bishop appears, there is a roar. He does not seem to notice the shouting, yelling, hooting, screaming, cursing, and he moves obediently as Calcraft places him beneath the beam, which faces south to Ludgate Hill; his last glimpse will be of thick fog, as Calcraft pulls a cloth sack over his head and puts the noose around his neck. The crowd is pleased with the preparation and begins to cheer. It is likely that Bishop knows of Calcraft’s reputation for ineptitude—choosing too short a drop, he has had to hang on the backs of the condemned to ensure their necks break—and he often stinks of brandy at his public appearances. Williams’s conversation with Whitworth Russell at the foot of the stairs has delayed him by two minutes, so Bishop stands alone, not moving a muscle or making a sound.

Williams appears, totters to the edge of the scaffold, and bows to the crowd. Why is he doing this? Why? Does he think he’s a performer on a stage? Is it a gesture he has seen the condemned make at executions? Is he trying to show remorse to the Mob he preyed on? The crowd screams and jeers and curses him. Shaking violently, he is led to the beam, hooded, and noosed. Cotton encourages both men to pray, and Williams does this eagerly, calling out the words along with the churchman, who, midsentence, gives Calcraft the signal for the drop, and both men fall.

Bishop dies instantly. But Williams is seen drawing his legs upward several times, with immense effort, while his neck and chest muscles throb; it is five minutes until his legs stop twitching. By which time, Cotton, the sheriff, the undersheriffs, and the paying visitors are on their way back through the prison to enjoy the breakfast that ancient tradition specifies on the occasion of executions at Newgate.

* * *

The excitement of the burkers

being “turned off” has led to a catastrophe at the southern end of Giltspur Street. The wooden barrier there has collapsed and many people are crushed in the panic. By a quarter to nine, an entire ward at St. Bartholomew’s is filled with injured spectators. Ribs are crushed, limbs are broken, flesh torn, but surprisingly, no one has been killed. Robert Mortimer, the Nova Scotia Gardens tailor who cut his throat rather than give evidence, is in Bart’s too, sitting up chatting and expected to make a full recovery.

* * *

It is nine o’clock,

and time for the bodies to be cut down, although this is scarcely the right term, since modern executions involve the rope’s being connected to a chain, which is attached to the beam by a hook kept in place by a screw and bolt. This arrangement is seen as a great advance. Calcraft simply turns the bolt and Bishop and Williams fall into the cart waiting below the scaffold. The crowd loves this. The bodies are covered by two sacks and then the cart is driven by the city marshall, wearing full ceremonial regalia, to 33 Hosier Lane, the house rented by the Royal College of Surgeons for the official reception of the bodies of executed murderers. It’s only a short distance—really just behind the Fortune of War. The cart moves in a slow, stately manner, and the crowd appears to enjoy the ritual and the costume of this traditional journey. They’d love to get their hands on the corpses, and the police have their job cut out for them keeping people back as Bishop and Williams are carried into No. 33.

It’s quite a reception they get: Sir William Blizard himself, eighty-eight-year-old president of the Royal College of Surgeons, has come to Hosier Lane in his college robes. He’s there, along with the entire court of the college, to officiate as William Clift, conservator of the college library and museum, draws his knife—ceremonially—across the chests and stomachs of Bishop and Williams, creating large cruciform wounds on each man.

3

Then the two are—ceremonially—stitched back up again before presentation to the anatomists. Having witnessed the opening and closing of the bodies, the city marshall leaves. Calcraft, having been given the men’s clothes and their nooses, beats a retreat too—these are his perks, and he will make money exhibiting the trophies. (Calcraft isn’t particularly interested in his job, preferring gardening, breeding prize rabbits, and caring for his pet pony; he is also said to be good with children.)

4

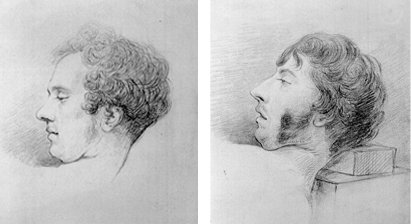

William Clift sketches the dead men and will later work these drawings up into likenesses that, many will say, are undoubtedly the faces of monsters.

The true likenesses of Thomas Head and John Bishop sketched by William Clift of the Royal College of Surgeons

Now Bishop and Williams take their leave of each other for the last time (though to be fair, they have known each other only for five months). Bishop is heading for King’s College, as a reward for Richard Partridge and Herbert Mayo, while Williams is off to the Great Windmill Street School, where George Guthrie and Edward Tuson are waiting for him.

FIFTEEN

The Use of the Dead to the Living

And once the scalpels are set to work, it becomes clear what manner of men these were, and how and why these murders came to be committed. At King’s College, Bishop had a lecture on medical jurisprudence read over him as he lay on the slab before once again being sliced from throat to abdomen, and across the chest, this time by Richard Partridge as Herbert Mayo stood by. Bishop, it was discovered, had an extraordinarily good physique, proving far more useful as a specimen than the produce he used to deliver. “A more healthy or muscular Subject has not been seen in any of the schools of anatomy for a long time,” cooed the

Morning Advertiser

. “The body presented a remarkably fine appearance across the chest. The deltoides were splendidly developed, and the pectorals, major and minor, were particularly displayed.”

1

Bishop was five feet seven inches tall and had an inordinate amount of body hair; at some point in his life he had broken both his legs, and he had two scars on his chin—perhaps an inexpertly scaled graveyard wall had left its imprint. The rope had bitten deep into the flesh on the left side of his neck. It was also discovered that Calcraft had made yet another hash of his job: Bishop’s spinal cord was intact. With the top of the skull carved off, Bishop’s brain was reported to look as though it was in an “unhealthy” state; the observers deduced that this was visual evidence of the mental anguish he had been suffering in the days before his death.

Later, but before he began to smell, Bishop was set up as an exhibit in a room next to the anatomical theater at King’s College; a huge crowd came to see the London Burker, who had been disemboweled and had had all his various cuts sewn up with thick twine. Later still, when he ceased to be a moneymaker, Bishop was gradually stripped down to the bone by the students and lecturers of King’s.

The clothes that Bishop had died in, alongside Williams’s, were exhibited by Calcraft in a private house in Sun Street, Shoreditch, for “only a penny,” according to the advertisements.

The dissection of Williams’s body caused a minor riot. For a fee, the curious were allowed into the dissecting room, where Edward Tuson and George Guthrie were at work. (Guthrie had put his request in early, writing to the secretary of the Royal College of Surgeons on 4 December: “If May is not executed, pray do me the favour to beg Mr Clift to send to Windmill Street the best of the two remaining, for a natural skeleton.” But he was shortchanged, since King’s College was given “the best.”)

2

People gathered outside the school to wait for admittance, and a number of medical students decided to police the crowd—although there were Metropolitan officers on the spot—arming themselves with staves and chair legs, with which they threatened those on line. Inside, students helped themselves to locks of Williams’s hair. Two students were seen brawling close by the corpse (which had its eyes wide open); they had become drunk on pots of beer hauled up on ropes over the heads of the crowd and in through the school windows. The police informed Tuson that the “exhibition” must end immediately since the noise from inside and around the school was disturbing residents.

3

Those who did gain admittance would have seen Williams’s tattooed forearms—which should have settled the issue of his true identity once and for all. But the tattoos just led to more confusion. In 1827, when his “distinguishing marks” had been so carefully sketched into a prison ledger, the authorities had noted tattoos of two intertwined love hearts shot through with arrows on his right forearm, and four letters on his left forearm. The latter now also featured a number of crudely drawn flowerpots, an anchor, and a scroll surrounding the four letters. In 1827, these had been transcribed as “T.H.N.A,” the “N.A.” assumed to be a sweetheart and related to the hearts and arrows on his right forearm. But William Clift, conservator of the Royal College of Surgeons museum, sketched the letters into his diary as “JOHN HEAD,” while a newspaper reporter transcribed them as “J. HEAD.” Pierce Egan, author of

Life in London,

also saw “JOHN HEAD” when he viewed the body, written above the letters “C.E” (never explained), and Egan wrote to the

Times

expressing his view that the truth of the killer’s confession was to be doubted, since he had signed the document “Thomas Head,” not “John.”

4

But Head had consistently described himself as “Thomas” in all the documentation that mattered: his wedding certificate, at his Old Bailey trial for theft, his entries in prison ledgers. Did Thomas decide to inscribe himself “John” at some point in Millbank or upon his release? Or were Clift and Egan mistaken in what they saw on the forearm?