The Italian Boy (40 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

The Savoyard forsook, to roam

For wealth and happiness in ours.

And pitying thousands saw the boy,

Feeding the tortoise on his knee;

And beauty bright, and childhood coy,

Oft flung their mite of charity.

And as he rested on the stone,

His organ tun’d to some old air!

Men paus’d at its familiar tone,

And left their little tokens there.

Et cetera.

In a similar way,

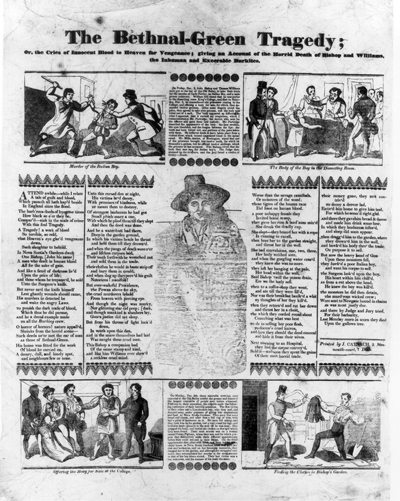

The Trial and Execution of the Burkers for Murdering a Poor Italian Boy,

a broadsheet produced by the most successful of cheap publishers, James Catnach (and so shoddily cobbled together that it reports James May being executed), contains this verse:

’Tis of a poor Italian Boy, whose fate we now deplore,

Who wandered from his native land unto old England’s shore;

White mice within his box confin’d he slung across his breast,

And friendless, for his daily bread, through London streets he prest.

From the cheapest broadsheet to the

Times

and the Houses of Parliament, it was decided that the Italian Boy case had revealed London, the world’s wealthiest city, failing in the duties of care that its superiority forced upon it. That a nation as great as Britain had let down a young stranger from another land provoked much striking of attitudes. A

Times

editorial on 10 November fulminated against the “wretches” who had “picked up from our streets an unprotected foreign child, and prepared him for the dissecting knife by assassination.” For the anonymous writer of

The History of the London Burkers,

a sense of national disgrace was invoked: “Can this be England—the most enlightened, the most civilised country of the globe? Alas! that England should now stand indelibly stained by guilt of so foul, so unnatural a blackness.”

Inexpensive broadsheets, plagiarizing the official accounts, meant that the poor could enjoy reading about trials and executions. Some printers were so keen not to spend money that they reused dated stock scenes from past murders.

Poor homeless Fanny Pigburn—kicked out by her landlord; afraid to return to her relations (for reasons unknown), unwilling to inflict herself on any other friend or family member, and so lacking in self-worth that she had dyed a new white bonnet black because she felt a white one was too smart for her to wear—was never sentimentalized. Carlo had been given the role of Daft Jamie (James Wilson), the eighteen-year-old murdered by Burke and Hare, whose sixteen known victims also included Mary Paterson, eighteen, who was so fine looking that her corpse was sketched and painted at Dr. Knox’s school and preserved in spirits.

12

But Fanny—pockmarked, skinny, fond of a drink, unmarried mother of two children she could not afford to care for—was not considered worthy of commemoration. Similarly, young Cunningham of Bishop’s confession was dully British, a London street boy, a runaway quite possibly surviving on the fringes of Smithfield’s criminal culture, having none of the Latin glamour of Carlo or the pathos of Daft Jamie. In five years’ time, Charles Dickens would give a character and dialogue to boys like Cunningham, bringing them into focus with the creation of the Artful Dodger and Charley Bates in

Oliver Twist,

but until then, London urchins appear in writing as a disreputable composite—dirty, dishonest, and barely human. “Your true London boy of the streets [has a] mingled look of cunning and insolence,” wrote journalist Charles Knight; while the author of the 1832 penal-reform volume

Old Bailey Experience

decided “they have a peculiar look of the eye … and the development of their features is strongly marked with the animal propensities.… They may be known almost by their very gait in the streets from other persons. Some of the boys have an approximation to the face of a monkey, so strikingly are they distinguished by this peculiarity. They form a distinct class of men by themselves.”

13

* * *

Meanwhile, trade was as brisk as ever

in Nova Scotia Gardens. Broadsheet sellers were crying out their titles and opening lines, and various religious tract societies were cashing in with fire-and-brimstone pamphlets on the wages of sin, with particular reference to the Late Murders. Even during a long downpour, the atmosphere was that of a village fair. The tours of No. 3 were still attracting hundreds of people. An elegantly dressed woman was seen to stoop down and scoop up water from the fatal well in order to taste it, while outside the front of the cottage, a lollipop peddler had set up a stall to sell sugar figurines of three burkers dangling from a miniature sugar gallows (a passerby was heard noting May’s reprieve and suggesting the confectionery be adapted accordingly). The talk of local women was about how Bishop and Williams’s punishment should have been longer and more painful. Inside the house, a self-appointed master of ceremonies was pointing out to visitors the relevant parts of No. 3, using a large stick. “This here was the wery bed wot he and his woman slept on,” he announced in the Bishops’ bedroom, though it is surprising that the bed had survived the first waves of visitors—perhaps a replacement had been installed in order not to disappoint.

14

A better-quality representation of Carlo sold as a print after the trial; engraving by J. Thomson after J. Hayes

A contemporary account reveals the more typical entertainment available for high days and holidays in the vicinity during those years, and puts the House of Murder hubbub into perspective. The anonymous essayist who contributed the article “Four Views of London” to the

New Monthly Magazine

described a Whitsuntide holiday trip he had made to Spitalfields, just south of Bethnal Green, his first visit to the area in thirty years and his chance to note its shocking decline since the collapse of the silk trade. For the poor, a holiday treat was tea in a tea garden, where two pennies was the price of hot water and crockery, but the tea leaves were not supplied. The writer watched as families sat on a blackened lawn, the entertainment consisting of one improvised swing for the children, a tiny, covered skittle ground, and a soaped pole to climb. For spectacle, the publican compelled an ill-looking boy to pick up a hundred pebbles within a set time. The eyewitness noted “an entire absence of all mirth and enjoyment.”

15

* * *

In Radical circles,

Bishop and Williams were providing material for satirical entertainment.

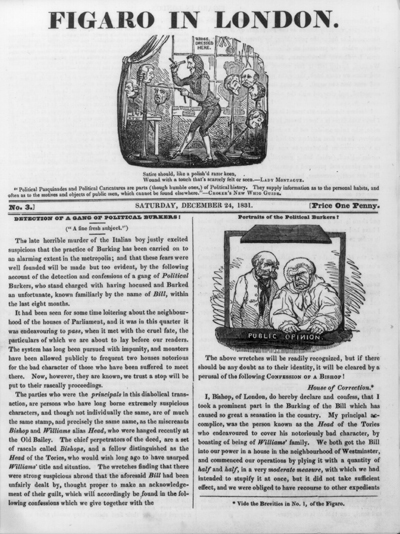

Figaro in London

was a scurrilous, antiestablishment weekly newspaper (price one penny) that took its name from the famous French daily and throughout its short life campaigned vigorously for electoral reform. In its Christmas Eve edition, 1831, the details of the Italian Boy case were used to lampoon the bishop of London—Charles Blomfield—and the duke of Wellington, who had been prominent among parliamentarians who had killed off the Reform Bill in October 1831: “I, Bishop, of London, do hereby declare and confess that I took a prominent part in the Burking of the Bill which has caused so great a sensation in the country. My principal accomplice was the person known as the Head of the Tories who endeavoured to cover his notoriously bad character by boasting of being of William’s family. We both got the Bill into our power in a house in the neighbourhood of Westminster, and commenced our operations by plying it with a quantity of half and half, and in a very moderate measure, with which we had intended to stupefy it at once, but it did not take sufficient effect.”

16

This Radical, pro-Reform journal, edited by Henry Mayhew, used the Italian Boy trial to lampoon the anti-Reform duke of Wellington and bishop of London, shown wearing a smock frock.

But thrills, pathos, and laughter were not Bishop and Williams’s principal legacy. Twelve days after their execution, Henry Warburton, MP, introduced his second Anatomy Bill to the Commons; by 20 December, it was having its second reading. In 1829, Warburton’s original bill—to make the unclaimed bodies of paupers who died in workhouses and hospitals available to teachers of anatomy for dissection—had been passed by the Commons but thrown out by the Lords. As with the Reform Bill, the upper house rejected attempts to tinker with God’s natural order—the aristocracy had ordained rights and privileges but also had a duty of care toward its inferiors, including their corpses. No upstart doctors should be allowed to interrupt this beautiful, natural, sacred hierarchical design for society.

As with the original bill, the opponents of Warburton’s second attempt at legislation comprised a broad coalition of, on the one hand, Tories who believed the traditional social order was under attack and foresaw the potential for further civil unrest if such a socially divisive act were to be passed and, on the other, Radicals who believed the poor should never become fodder for middle-class self-betterment.

Sir Frederick Trench, Tory member for Cambridge, told the Commons that Warburton’s measure should be renamed “a Bill to Encourage Burking,” claiming that legalizing the supply in no way removed the premium for hastening a relative’s death. All that was needed to prevent another Bishop and Williams was for surgeons to examine far more carefully the Subjects that were offered to them, said Trench.

17

Similarly, Cresset Pelham, the member for Shropshire, recognized that Warburton’s bill treated the human body as an item of trade, while merely bringing down the price of such a commodity. “The bill would give a legal encouragement to the traffic in human blood,” said Pelham, who suggested that the best way to put an end to burking would be to inflict stronger punishment on the “receivers.” Alexander Perceval, Tory member for Sligo, also wanted the onus to be placed on the surgeons and said that, in his view, possession of a Subject should be upgraded from a misdemeanor to a felony.

The bill’s most vociferous opponent, Henry “Orator” Hunt, capitalized on the unsavory reputation of anatomy schools and spoke of the lack of respect that was shown to corpses by teachers and students, claiming that “the cutting up and mangling of the bodies of human beings was done with as little concern in those human shambles as the bodies of beasts were cut up in Newgate, Smithfield or any other market.” Hunt professed to have it on the best authority that “the conduct of the young students in the dissecting-room was too often perfectly disgusting—too disgusting to be described even in an assembly like that, composed as it was entirely of men.”

18

(Surgeon George Guthrie had given the game away when he wrote, in 1829, an open letter in which he urged anatomists to end the pretense that dissected corpses had a decent burial once they were finished with. Since the flesh was removed at a slow rate, he wrote, it could not be stored until the skeleton had been revealed; the flesh simply ended up with all the other refuse produced by the schools.)

19