The Italian Boy (28 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

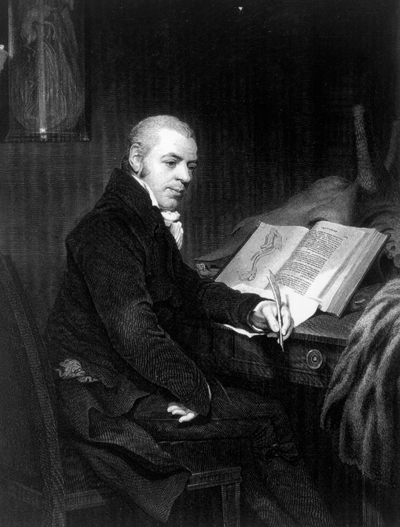

Anatomist Joshua Brookes was frequently attacked by resurrectionists for failing to pay them properly.

Joshua Brookes, an unlucky man in so many ways, comes down to us as the London anatomist most closely connected with public fury. Perhaps he did not have the guile to be as circumspect as other medical men; perhaps he was too proud to care about discretion. One night, date unknown, disgruntled resurrectionists, angry that Brookes would not pay them a retainer, dumped two badly decomposed bodies near his school. Two “well-dressed ladies” stumbled over them in the dark, and their screams caused a mob to assemble outside the Brookesian; the anatomist, afraid of a lynching, sought refuge in the Great Marlborough Street police court and magistrates office.

24

Brookes’s refusal to agree to resurrectionists’ financial terms got him into trouble on at least one other occasion, when a resurrection gang broke into his school at night and slashed to pieces a body lying on his dissection table; again, Brookes needed help from Great Marlborough Street. In addition to his having to flee to the magistrates office for protection, it was reported that Brookes’s school was frequently raided by constables from that very police office. He is likely to have been the victim of informants, both snatchers and Bats, having managed to arouse the dislike of both.

Brookes is the nearest London has to a Dr. Knox figure. When Knox was discovered to have been the buyer of Burke and Hare’s victims and suspected of having known how the corpses had been obtained, he was besieged in his Edinburgh home by crowds and his windows were smashed, while his effigy was hanged, then torn apart; in another part of the city his image was burned. But the greater damage was done to Knox by his peers; gradually, colleagues and acquaintances began to withdraw support, and Edinburgh’s most brilliant surgeon found himself unable to obtain the humblest post. The social shunning forced him to leave Edinburgh for London, where he was also ostracized, and dwindled into poverty and a lonely death in 1862. Brookes, too, died poor and alone, in 1833, but without the ignominy endured by Knox.

25

* * *

There are other, smaller, ripples.

Here is poet Thomas Hood’s 1826 portrayal of Londoners’ anxieties about the fate of their bodies after death:

’Twas in the middle of the night

To sleep young William tried;

When Mary’s ghost came stealing in

And stood at his bedside.

Oh, William, dear! Oh, William, dear!

My rest eternal ceases;

Alas! my everlasting peace

Is broken into pieces.

I thought the last of all my cares

Would end with my last minute,

But when I went to my last home

I didn’t stay long in it.

The body-snatchers, they have come

And made a snatch at me.

It’s very hard them kind of men

Won’t let a body be.

You thought that I was buried deep

Quite decent like and chary;

But from her grave in Mary-bone

They’ve come and bon’d your Mary!

The arm that us’d to take your arm

Is took to Dr. Vyse,

And both my legs are gone to walk

The Hospital at Guy’s.

I vowed that you should have my hand,

But Fate gave no denial;

You’ll find it there at Dr. Bell’s

In spirits and a phial.

As for my feet—my little feet

You used to call so pretty—

There’s one, I know, in Bedford Row,

The other’s in the City.

I can’t tell where my head is gone,

But Dr. Carpue can;

As for my trunk, it’s all packed up

To go by Pickford’s van.

I wish you’d go to Mr. P.

And save me such a ride;

I don’t half like the outside place

They’ve took for my inside.

The cock it crows—I must be gone;

My William, we must part;

But I’ll be yours in death, altho’

Sir Astley has my heart.

Don’t go to weep upon my grave

And think that there I’ll be;

They haven’t left an atom there

Of my anatomie.

26

* * *

The link between anatomists

and resurrection men had become part of urban folklore. “If you go to stay at the Cooks, they’ll cook you!” Anne Buton told her grandmother on 19 August 1831. The impoverished eighty-four-year-old Caroline Walsh had decided to take up the offer made to her by one Edward Cook and his common-law wife, Eliza Ross, of a bed in their rooms at Goodman’s Yard, Minories, east London. Buton told Walsh that the pair were body snatchers, warning, “They’re sure to sell you to the doctors.”

Buton never saw her grandmother alive again, and when Eliza Ross eventually told Buton that Walsh had left Goodman’s Yard after just one day, Buton mounted her own search of east London’s streets, workhouses, and hospitals. By late October, the newspapers had begun to take Buton’s worries seriously, and under the heading “Mysterious Disappearance” the

Globe and Traveller

of 28 October reported that the old woman may have been “burked for the base object of selling the body for anatomical purposes.” Nine days before the Italian Boy arrests, Ross was taken into custody on suspicion of murder; her twelve-year-old son had told the police that Ross, acting alone, had suffocated Walsh on the evening of 19 August, had put her body in a sack, and had lugged her off to be sold at the London Hospital, three-quarters of a mile away in Whitechapel Road. On 6 January 1832 at the Old Bailey, Eliza Ross was found guilty of murder and was executed three days later.

27

Surgeons at the London Hospital vigorously denied that they had bought any cadavers in August, and there is evidence to suggest that Cook and Ross’s neighbors were intent on blackening the couple’s name. One of the lodgers who gave evidence claimed that he had often seen coffins in their parlor—an obvious concoction, since no resurrectionist ever went to the trouble of lugging a coffin up out of the grave.

As with the dead boy in the watch house of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, identity proved problematic in the Walsh case. An old woman who had died on 3 September after being taken to the London Hospital with a broken hip was twice exhumed for Anne Buton to identify. But this old lady proved to be Catherine Welch, sixty-one, originally from Waterford in Ireland; she was tall but stooped and feeble, with no front teeth, feet in very poor condition, and filthy skin and matted hair. She had been wearing a blue gown and a black silk bonnet, all her clothing being verminous. Welch had made her living selling matches in the streets but had broken her hip in a fall in Whitechapel on 20 August. Caroline Walsh, Anne Buton’s grandmother, hailed from Kilkenny, was energetic, did not stoop, had a full set of teeth, and looked clean. She was a peddler of laces, tapes, and ribbons. Her clothing consisted of a black gown, a black bonnet, and a blue shawl (stained), and she wore men’s shoes. In a telling detail of the case, Buton had also searched for her grandmother at the houses of those “who were very kind to her [Walsh] for many years by giving her victuals &c.”

But where had Anne Buton got her notion that burkers cooked or boiled their victims? Poet John Clare, on his first visit to London from his native Northamptonshire in March 1820, learned some “fearful disclosures” from his city-dwelling friend the artist Edward Rippingille, who described to Clare “the pathways on the street as full of trap doors which dropped down as soon as pressed with the feet, and sprung in their places after the unfortunate countryman had fallen into the deep hole … where he would be robbed and murdered and thrown into boiling cauldrons kept continually boiling for that purpose and his bones sold to the doctors.”

28

Perhaps Clare’s friend was simply having fun frightening a naive countryman; but as with Anne Buton’s warning to her grandmother, the notion of boiling, cooking, and consuming had become intermingled with the notion of dissection and anatomy. It crops up again in the Nattomy Soup incident of May 1829, in which an inmate at Shadwell workhouse in east London claimed that the institution’s broth included human remains; a local magistrate sentenced the man to twenty-one days in jail for making such an allegation.

29

* * *

Dr. James Craig Somerville,

who was teaching at the Great Windmill Street School in the late 1820s, had a curious experience of the public’s anxiety. He told the Select Committee on Anatomy that he had only started to be “annoyed” by locals since the occasion on which he took in a murderer’s corpse to dissect.

30

The dissection of a felon was an event that the public could—and did, in great numbers—pay to witness. Many surgeons believed that allowing the public in helped dispel ignorance about dissection; others worried that it would have exactly the opposite result. (Dr. Knox himself believed that “the disclosures of the most innocent proceedings even of the best-conducted dissecting rooms must always shock the public and be hurtful to science.”)

31

Somerville said that he was now plagued by members of the public wanting to see each body “whom they believed may be a victim.” A victim of what? Of being resurrected? Of dying accidentally and ending up as a Subject? Or a victim of something more sinister? This tantalizing throwaway remark is the best evidence we have that, even before Burke and Hare, there may have been widespread suspicion that individuals were being killed in order to supply the surgeons.

* * *

Sir Astley Cooper’s efforts

to shield his activities from public view also testify to the general mood. The ground floor of Cooper’s private house in St. Mary Axe, just east of Bishopsgate, contained a dissecting room, with windows painted so that his neighbors would not be offended or passersby alarmed. Upstairs, in his attic, up to thirty dogs at a time were kept, stolen from the street by Sir Astley’s butler, Charles, who would also inveigle youngsters, Fagin-style, into stealing stray dogs or luring them from their owners, paying the boys half a crown per beast. (And Sir Astley had once called body snatchers “the lowest dregs of degradation.”)

32

According to his biographer—and nephew—Bransby Cooper, Sir Astley killed the dogs in order to discover whether a catgut ligature tied around the carotid artery would dissolve (it wouldn’t).

33

In a gorgeous example of the hypocrisy and arrogance to which the clan Cooper seems to have been so prone, Bransby makes the perpetrator the injured party: “These circumstances, to which surgeons were unavoidably rendered victims, perhaps may be considered as some of the principal causes which have prevented the members of the medical profession maintaining that rank in society of which the usefulness of their purpose rendered them justly worthy.”