The Italian Boy (23 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Edinburgh’s Dr. Knox, purchaser of Burke and Hare’s produce, was another who preferred to work on humans: “I have, all my life, had a natural horror for experiments made on living animals, nor has more matured reason altered my feelings with regard to these vivisections.… A minute and careful anatomy, aided by observation of the numerous experiments made by nature and accident on man himself, seems to me to present infinitely the best and surest basis for physiological and pathological science.”

26

Humanity Dick was never able to bring an action against a vivisectionist; his attempts to pass such a measure failed in Parliament. But in pursuing cases of ordinary, everyday cruelty, he became legendary, and his London court appearances—as prosecutor—often found him in front of George Rowland Minshull, who obtained many contributions to the courtroom swear box (proceeds to the poor) as a result of Martin’s endless stream of exasperated “By God”s and “Oh God”s. The two men seem to have enjoyed a part-jocular, part-peevish series of exchanges in the mid-1820s, such as this, at Bow Street. Minshull had suggested that a man could judge for himself how much chastisement his own horse might require, to which Martin called out, “By God, if a man is to be the judge in his own case, there is an end of everything!”

“I fine you five shillings for swearing,” said Minshull.

“I’ll pay up,” said Martin.

“No, I was joking,” said Minshull, who went on to acquit the defendant, who had been charged with cruelty to a horse. Martin was furious, quoting Macbeth (and shouting): “Time has been, that when the brains were out, the man would die,” as he leapt across the courtroom to make his point.

“My brains may be out,” said Minshull, “but I cannot make up my mind to convict in this case.”

“Then it is time that you were relieved from the labours of your office!”

“Well that was a very kind and gentlemanly remark, I must say,” said Minshull, “but I am going to keep my temper, whatever you do, and I dismiss the case.” And Martin flounced out.

27

Martin was determined to extend his 1822 anticruelty act to protect all animals, including domestic pets, to ban bull- and badgerbaiting, cock- and dogfighting, and to improve conditions in abattoirs. He failed to get further bills passed in 1823, twice in 1824, three times in 1825, and three times in 1826. On 16 June 1824, the day after the loss of Martin’s Slaughtering of Horses Bill (an attempt to force slaughterhouse owners to keep horses well fed while they awaited death), a meeting took place at the inappropriately named Old Slaughter’s Coffee House.

28

The Friends of the Bill for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals resolved to become a more permanent body, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (to be given its “Royal” prefix by Victoria in 1840). Those assembled pledged to redouble their efforts to police the behavior of cabmen and drovers and to publish tracts and write letters to the great and good on why mistreating brute beasts was immoral. Such activities could take time: one Charles Merritt told the 1828 Select Committee on Smithfield that it had taken him the best part of a day to get a drover’s boy arrested for injuring a bullock in Oxford Street. A growing number of anticruelty campaigners took to patrolling Smithfield, reflecting a growing passion for personal intervention in the face of the apparent unwillingness or inability of the constables appointed by the Corporation of London to police Smithfield Market effectively. (The Metropolitan Police had no jurisdiction in Smithfield; not until 1839 did the City exchange its parochial constables for a body modeled on the Met.) Eight to ten constables were supposed to be on hand at any time during the day, but there were frequent complaints that officers were never to be found or, if found, would do little to act against a cruel drover.

29

Shifts in attitudes toward animal cruelty had wide-ranging implications. Opposition to the 1800 and 1809 anticruelty bills had largely focused on two issues. First, it was felt to be a gross infringement of liberty for a man to be prohibited from doing as he saw fit with his property—living property included (the same reason that, short of murder, a man could do as he pleased with his wife). Undue interference in private lives was to be avoided as far as possible (though some private lives were considered more worthy of protection than others). Martin’s Act cleverly got around the freedom-of-the-individual objection by framing the legislation to apply to those who had

charge

of a beast; its result, though, was a crackdown on workingmen, who merely had charge—not ownership—of horses, cattle, and donkeys. Second, there was doctrinal objection to animal protection, at least when the Lords came to debate the measure. Why should animals be considered the equal of man when he was given dominion over every living thing that moves upon the earth? The concept of an animal’s having feelings and legal rights was seen as yet one more eccentric notion held by Methodists, Quakers, Baptists, Evangelicals, and other nonconformists who made up a large and vocal part of the anticruelty lobby.

30

Many of Martin’s supporters conflated their attacks on animal cruelty with opposition to ancient aristocratic privilege and to arcane, outmoded civil processes and institutions, and many different threads of protest were to be interlinked in the literature of animal-cruelty campaigners. The 1823

Cursory Remarks on the Evil Tendency of Unrestrained Cruelty

pamphlet, for example, worked itself up into a purple passage eliding all manner of social ills perpetrated in unreformed, aristocratically misruled Britain: “Man has the vanity, the preposterous arrogance, to fancy himself the only worthy object of divine regard; and in proportion as he fancies himself such, considers himself authorised to despise, oppress, and torment all the creatures which he regards as his inferiors … and thus the proud and voluptuous in the higher ranks of society too often regard the humble and laborious classes as beings of a different cast, with whom it would be degrading familiarity to associate, and whom, whenever they interfere with their pleasures, their interest, or caprice, they may persecute, oppress and imprison. [This last was a reference to the Vagrancy Act, then being debated in Parliament.] … Thus men in the lowest stations become, in their turn, the persecutors and tormentors of the brute creation, of creatures which they regard as inferiors.” The chain of evil passed downward from the aristocracy to Smithfield, where the cattle appeared to take on Christlike attributes, exhibiting, according to

Cursory Remarks,

“the most patient endurance of every kind of persecution” and having “a harmless, unresisting, uncomplaining nature.”

31

Impassioned rhetoric such as this, combined with zealous personal intervention, appeared to be winning the day. Humanitarianism was becoming attractive to those seeking a new respectability—those who felt themselves on the verge of getting the vote—and increasing support was being shown for moves that would distance the new industrial/mercantile age from a past perceived as barbarous. Some of the more obvious excesses were being eradicated by legislation: the slave trade was abolished in the British Empire in 1807, and the ownership of slaves in 1833; the use of child labor began to diminish with the passing of the first Factory Act in 1833. The Bloody Code was crumbling: the burning of female felons ended in 1790; hanging, drawing, and quartering was abolished in 1814; the last beheadings were in 1820; the stocks, the whip, the pillory, and the gibbet would all fall idle by 1837. (London’s last set of stocks would stand disused for many years in Portugal Street, James May’s former haunt.) One of the last public whippings in London took place in 1829, when a thirteen-year-old boy was flogged for 150 yards while tied to the end of a moving cart for stealing a pair of shoes; though no one attempted his rescue, the crowd that gathered was vocal in its opposition.

32

The old was becoming repugnant, and Smithfield offended on many levels; everything about the place stood in direct opposition to the impulses of those bent on reforming, modernizing, cleansing, ordering, making open and visible. The very topography of “this old field of cruelty” appeared to modern eyes to embody and perpetuate the sins of ages past.

33

Until the middle of the thirteenth century, a small wooded section of the Smoothe Field called the Elms, which lay between today’s Cowcross and Charterhouse streets, had been the place of public execution. In 1542, Henry VIII devised the spectacle of the boiling to death of offenders, to take place in Smithfield (one of his kitchen staff, who had been accused of poisoning, died in a vat, slowly, in this way; a serving woman met the same fate the following year). In the next decade, Mary Tudor had forty-five Protestants burned close to the gates of St. Bartholomew the Great, and her sister, Elizabeth I, sent Catholics to the flames. Two centuries later, the convoluted lanes running around Turnmill Street, West Street, Field Lane, Saffron Hill, Cowcross, and other thoroughfares near the Fleet were colloquially known as Jack Ketch’s Warren, after the seventeenth-century executioner; the Warren was where gallows fodder hid from the law and bred new sinners. These festering piles of wooden buildings cut off the south from the north, while the higgledy-piggledy, queer, and quaint alleys and courts, with their antique names (Black Boy Alley, Swan Inn Yard, Bread Court), were increasingly seen as harboring immorality, criminality, disease, and civil unrest—right in the heart of the wealthiest city in the world.

34

The sinuosity and complexity of the Warren confounded those who attempted to enter and investigate these ancient spaces: to the horror of one surveyor and public health campaigner, Frying Pan Alley, off Turnmill Street, was found to be twenty feet long but just two feet wide.

35

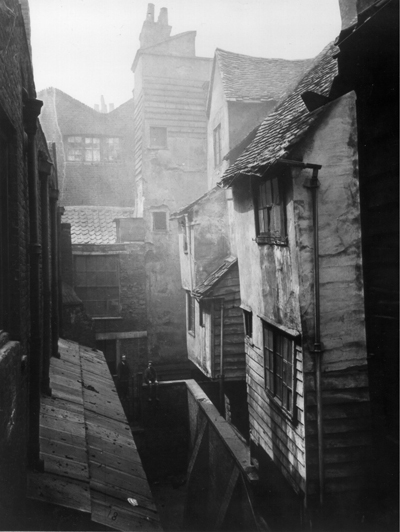

Tudor/Stuart housing in Cloth Fair, Smithfield. Although it was considered squalid in the 1830s, its destruction at the end of the nineteenth century provoked an outcry.

But it was only the outsider who was bewildered by the twists and turns of Smithfield. Those who lived there or worked there were able to negotiate it with ease. When Thomas Williams was sought for the theft of the copper from his parents’ lodgings at 46 Turnmill Street, James Spoor, his parents’ landlord, was told that he could probably find the culprit at the Bull’s Head.

36

This pub was a right, a right, and a right again walk from Turnmill Street—and sure enough, there was Williams. The pub stood in a secluded court within a morass of tiny streets; but to those in the know it was simple to locate.

37

Cleanliness, godliness, and commercial progress—the Victorian trinity—would sweep much of the district away; the alleys and courts that remained were often no more than amputated stumps abutting the fine new thoroughfares that thrust through the region: Farringdon Road, Clerkenwell Road, Holborn Viaduct, Charterhouse Street, the Metropolitan railway line. The filthy Fleet would be locked into a conduit beneath Farringdon Road. Disease, the Victorians believed, was airborne; petty, and not so petty, criminality festered in dark, unseen quarters; trade was shackled by poor lines of communication and slowed traffic. Before the century’s end, Smithfield’s secrets would be laid open to the skies.

NINE

Whatever Has Happened to Fanny?

On Thursday, 24 November, two admission booths were set up outside Bishop’s House of Murder, as No. 3 Nova Scotia Gardens was now known. The police had asked John and Sarah Trueby, owners of Nos. 1, 2, and 3, if some arrangement could be made for visitors to enter the House of Murder five or six at a time, paying a minimum entrance fee of five shillings—a move officers hoped would prevent the houses being rushed by the hundreds who were thronging the narrow pathways of the Gardens and straining to get as close to the seat of horror as possible. Sarah Trueby’s grown-up son told Constable Higgins that he was concerned about his family’s property sustaining damage and asked Higgins and his men if they could weed out the rougher element in the crowd. Somehow, Higgins managed to maintain at least the pretense of decorum, and the

Morning Advertiser

later claimed that “only the genteel were admitted to the tour.” Nevertheless, the two small trees that stood in the Bishops’ garden were reduced to stumps as sightseers made off with bark and branches as mementoes—ditto the gooseberry bushes, the palings, and the few items of worn-out furniture found in the upstairs rooms, while the floorboards were chopped to pieces for souvenir splinters. Local boys were reported to have already stolen many of the Bishops’ household items, and around Hackney Road and Crabtree Row a shilling could buy the scrubbing brush or bottle of blacking or coffeepot from the House of Murder. All of which prompted journalist and historian Albany Fontblanque to ruminate on English morbidity and enterprise in the

Examiner

magazine: “The landlord upon whose premises a murder is committed is now-a-days a made man.… Bishop’s house bids fair to go off in tobacco-stoppers and snuff-boxes; and the well will be drained—if one lady has not already finished it at a draught—at the rate of a guinea a quart.… If a Bishop will commit a murder for £12, which seems the average market price, the owner of a paltry tenement might find it worth while to entice a ruffian to make it the scene of a tragedy, for the sale of the planks and timbers in toothpicks, at a crown each.”

1