The Italian Boy (22 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Another, more alarming market was held at Smithfield from time to time: making a “Smithfield bargain” referred to the sale by a husband of his wife and was believed in many working-class communities to be a perfectly valid form of divorce (it had its roots in Anglo-Saxon common law). The sale was usually prearranged, and the buyer was often a friend of the family or a neighbor who, motivated by pity, wanted to help bring an unhappy union to an end; the public nature of the sale was to validate for the community the ending of the marriage. At two o’clock on the afternoon of Monday, 20 February 1832, a man brought his twenty-five-year-old wife in a halter and tied her in the pens opposite the Half Moon pub, close to the gate of St. Bartholomew the Great. A crowd gathered and the auction began, with a “respectable-looking man” striking a deal for ten shillings; throughout, the woman made no complaint about her treatment.

12

Some twenty cases of wife selling at Smithfield are on record between the 1790s and the 1830s, though the true figure is likely to be higher.

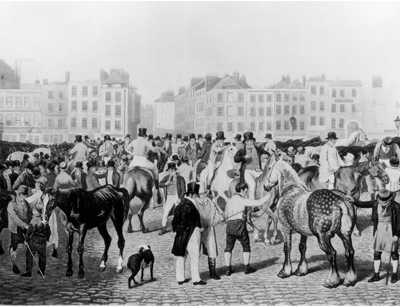

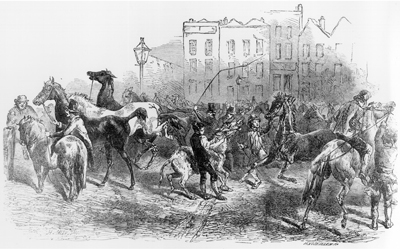

Two contemporary views of the Friday horse market at Smithfield—one sedate, one wild

Descriptions of Smithfield challenged even the most euphemistic of writers. It is clear that offal, excrement (“filth”), and urine (“steam”) had to be negotiated by a pedestrian. Quite apart from the stink and refuse from the market and the slaughterhouses, associated trades helped to contaminate the nearby streets—the sausage makers, tanners, cat- and rabbit-fur dressers, bladder blowers, tripe dressers, bone dealers, cat-gut manufacturers, neat’s-foot-oil makers. Here is Charles Dickens attempting to convey the aura of Smithfield to a family readership, in

Great Expectations:

“The shameful place, being all asmear with filth and fat and blood and foam, seemed to stick to me.” And in

Oliver Twist:

“The ground was covered, nearly ankle deep, with filth and mire; and a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney tops, hung heavily above.… Countrymen, butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and vagabonds of every low grade, were mingled together in a dense mass.”

13

Dickens did not attempt to address the issue of animal slaughter itself, which frequently took place in the cellars or back yards of ill-adapted private houses; but others, intent on reform, did not spare the detail. For the Smoothe Field that had been just outside the medieval city walls was now right in the center of a busy metropolis, the capital of a great and growing imperial power—and its goings-on were, frankly, not respectable.

14

These matters were handled better in France, the Select Committee on Smithfield discovered, and the abattoirs of Paris were analyzed and eulogized by committee witnesses. While local bylaws forbade any emission of blood from a slaughterhouse, it was, nevertheless, a regular sight across the pathways of Smithfield, and pedestrians would get blasts of hot, stinking air through street-level gratings since animals were often kept and killed below ground.

15

Passersby glancing left or right into a court or yard where a butcher worked could find themselves witnessing a killing. It was alleged by various witnesses before the 1828 Select Committee on Smithfield that sheep were often skinned before being completely dead; it was observed that an unskilled slaughterman could require up to ten blows with an axe to kill a bullock; and while an inspector was supposed to be notified before the slaughter of any horse, the rule was said to be broken more often than kept, and horses were observed up to their knees in the weltering remains of their fellow creatures, maimed and starving and showing obvious signs of distress as their fate dawned on them.

16

George Cruikshank’s

The Knackers Yard

; or,

The Horse’s Last Home

, 1830, shows the appalling conditions in slaughterhouses.

The cruelty that was meted out to creatures in Smithfield was quite apparent to the passerby. While a goad on the end of a drover or market man’s rod or staff was supposed to be no longer than one-eighth of an inch, many were longer and were seen being used on the head, eyes, genitals, and shins of animals that were standing perfectly still; the “wake them” beatings just before daylight in winter were said to be particularly vicious. In the marketplace, cattle were arranged in “drove rings”—circles of around fifteen; nose in, tail out—and were kept in that formation by beatings. Hundreds of cows and bullocks stood crowded together in this way in the wide paved area just to the northwest of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital; this section was criss-crossed by pathways for pedestrians, with only a wooden handrail between beast and bypasser.

17

Walking this route was a challenge, given the slippery Smithfield terrain and especially so in the “black frosts of November.”

18

That Smithfield was often brighter by night than by day was confirmed by a witness before the Select Committee, who said that in winter the handheld lamps of the drovers and the street gas lamps meant that selling could continue after dusk fell in the afternoon. The newspaper columnist who wrote under the pseudonym Aleph, remembering the Smithfield of the 1820s, recalled that “if the day was foggy (and there were more foggy days then than now) then the glaring lights of the drover-boys’ torches added to the wild confusion.… The long horns of the Spanish breeds … made it a far from pleasant experience for a nervous man to venture along one of these narrow lanes, albeit it was the nearest and most direct way across the open market.”

19

Road traffic continued to travel across the quarter-mile stretch between the top of Giltspur Street and the southern end of St. John Street, and collisions with animals were common; beatings were used to move beasts out of the way of carts, coaches, and carriages, but hindquarters were frequently hit by passing vehicles.

* * *

The common,

all too visible brutality at Smithfield was to prove a major impetus in securing the world’s first legally enforceable animal-protection measures. In April 1800, a motion had been defeated in Parliament to ban bullbaiting and cockfighting; in 1809, a more broadly defined anti–animal cruelty bill was also defeated, though it had progressed farther than its predecessor before being lost. In May 1821, a similar bill was passed in the Commons but lost in the Lords; and then, in May 1822, a Bill to Prevent Cruelty to Horses, Cattle and Donkeys was passed by both Commons and Lords, gaining royal assent in July of that year. It was always to be known as Martin’s Act, after its mover, Colonel Richard Martin, MP for Galway.

20

Martin was popularly known as Humanity Dick, a nickname thought to have been given to him by George IV, with whom he was friendly, despite the king’s love of hunting and cockfighting.

21

He was also called Hair-Trigger Dick because of his overexcitability and his readiness to fight duels (he killed no one but inflicted and received a number of gunshot wounds). Martin was nearly seventy when his act was passed, but he was tireless in his drive to seek out brutality to animals and drag offenders before the magistrates; within a year of the act’s becoming law, 150 people were prosecuted in police courts for cruelty. Martin lived, like many other MPs of the day, in Manchester Buildings, a court of rented rooms on the river next to Westminster Bridge, and was often to be seen parading Whitehall and Charing Cross Road inspecting cabmen’s behavior and the condition of their horses.

22

A contemporary described him as “a meteor of ubiquity” who appeared to be all over London at the same time, ferreting out and exposing the ill treatment of animals.

The first prosecution to be brought under his novel piece of legislation came about after Martin paid a visit to the Friday horse market at Smithfield and secured the arrest of Samuel Clarke and David Hyde. Clarke was a horse dealer who had repeatedly struck a horse on the head with the handle of his whip to make it look more lively as it stood tethered to a rail; Hyde had severely beaten a horse as he was riding it, for the same reason. Both men were fined twenty shillings each. (The minimum fine was ten shillings, the maximum five pounds or up to two months in jail.) Martin also undertook a citizen’s arrest of a Smithfield butcher whom he saw breaking the leg of a sheep; Martin forcibly pulled the man away, even though a gang of drovers appeared on the scene and threatened him. He gave eyewitness evidence at the successful prosecution of a Smithfield dealer who regularly flung calves into a van with their legs tied together and cords around their necks; the creatures piled on top of one another and many suffocated. (In his defense, the dealer said that, if he was not allowed to do his job the way he saw fit, “gentlefolk would get no veal.”)

23

Martin was particularly alarmed at the use of vivisection in medical research. During the 1825 House of Commons debate on a bill that would broaden the scope of Martin’s Act, the member for Galway told the House how the French anatomist François Magendie (“this surgical butcher, or butchering surgeon,” Martin called him) had, on a visit to London, bought a greyhound for ten guineas (the going rate for a dead human) and nailed the dog’s paws and ears to an operating table and dissected its facial and cranial nerves one by one, severing its senses of taste, then of hearing, and announcing that he would perform a live vivisection the next day—if the dog was still alive.

24

Within the medical community, many London surgeons voiced their opposition to vivisection—in public, at least. The great John (“Fear God, and keep your bowels open”) Abernethy saw little value in such research, believing that observation, not experiment, was the key to physiological knowledge; whenever Abernethy did investigate animal anatomy, he insisted the beast be killed quickly and humanely before dissection. Sir Charles Bell, the eminent physiologist, believed there was little of use to humans to be learned from exploring animal physiology, and he had moral scruples, too: “I cannot perfectly convince myself that I am authorised in nature or religion to do these crudities,” he wrote in a letter to his brother George in 1822. Elsewhere Bell wrote: “Experiments have never been the means of discovery; and a survey of what has been attempted in late years in physiology will prove that the opening of living animals has done more to perpetuate error than to confirm the just views taken from the study of anatomy and natural motions.” To which Magendie, who was determined to fathom the mysteries of muscle movement, particularly that of the facial muscles, replied: “One should not say that to perform physiological experiments one must necessarily have a heart of stone and a leaning towards cruelty.”

25

In 1824, before a crowd of physicians, Magendie severed part of the brain of a dog, which fell down, stood up, ran around, then died.