The Italian Boy (45 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

* * *

Late one night

in December, dentist Thomas Mills was awoken by someone hammering at his door. When he looked from his window, a man below claimed to have a bad toothache—would Mills treat him? Despite the darkness, Mills could make out two other men lurking behind the first and saw that all three were in smock frocks and carried bludgeons. Mills refused to open his shop, and the three walked off, shouting threats of future violence.

* * *

Before Christmas

, Sarah Bishop took lodgings in Paradise Row, Battle Bridge, and Rhoda in nearby Edmund Street. Three miles west of Bethnal Green and a mile and a half northeast of Covent Garden, Paradise Row was mocked at the time for being distinctly unheavenly: lying behind a smallpox hospital, it was a half-built, half-tumbledown, undrained, unlit street whose piles of manure (human, horse, donkey, and dog) left it reeking and dangerous to health. But the living condition that most disturbed the residents was the presence among them of the kin of burkers. Newspaper reports stated that local women were refusing to let their children play outside so long as Sarah and Rhoda were known to be residing in the area.

Nothing more appears in the newspapers about Bishop’s and Williams’s widows and children, though four young Bishops—Thomas William, twelve, Frederick Henry, ten (actually twelve), Thomas, seven, and Emma, two—were admitted together to the Shoreditch workhouse on 5 March 1832, staying for three weeks. These seem likely to be the killer’s children, along with one older boy. Perhaps Thomas William was a cousin, since, when the three boys—without Emma—turned up at the workhouse again two and a half years later for a one-night stay, they were discharged to Thomas William’s father, described in the workhouse register as living in Norwood, south London. Frederick and Thomas Bishop were admitted once again, for two days, in April 1835.

3

After that, the children’s whereabouts and fates—how they felt about their parentage, whether they were shunned or were shown sympathy—are unknown.

* * *

Joseph Sadler Thomas

was never able to capitalize on the recognition he gained from his role in the Bishop and Williams investigation. Despite the eulogies that appeared in all the newspapers praising the New Police as a body, and Thomas as an individual officer, for securing the conviction of the London Burkers, his enemies never ceased to pillory him, and he was singled out for criticism for “high-handedness” during the Coldbath Fields Riot of 13 May 1833. This meeting of three hundred members of the National Union of the Working Class and their supporters took place on a large stretch of open ground just behind Coldbath Fields Prison and was broken up by an equal number of badly organized and belligerent Metropolitan Police officers, who managed to turn a good-humored gathering into a general brawl, with one fatality—a police officer’s.

But it was a more petty row that sealed Thomas’s fate. Just after the Coldbath Fields Riot, he was accused of victimizing a publican called Williams who had applied for a pub license in Seven Dials, Covent Garden. Thomas opposed the license, saying that there were already thirty pubs within 150 yards of Williams’s proposed venue, and Thomas was one of fifty local residents who signed a petition to limit the number of pubs in the area. Two magistrates (one of whom, Rotch, loathed the New Police, and Thomas in particular) complained to the Home Office about Thomas’s antipathy to Williams’s license application, and at the justices’ behest, Thomas was suspended from the Metropolitan Police for five weeks until the commissioners themselves intervened and apologized to Thomas for this overreaction.

Thomas felt that he had been humiliated once too often “in a neighbourhood where I had been for 20 years with an unpolluted character”; he would, he said, “as well have met my death” than endure the disgrace of suspension.

4

On 22 July 1833, he resigned from the Metropolitan Police and with his wife and three children moved north, becoming deputy constable of Manchester’s “old police” and among the first of Manchester’s “new” Borough Police Force, when this Met-style organization was set up in 1839. His salary—six hundred pounds per annum—was three times his Covent Garden pay.

He did not stay long with the new force, however; his health deteriorated, and for the last two years of his life he was unable to work and was supported by a public subscription—a vote of thanks from many in Manchester who had appreciated his work as a constable. He died in October 1841.

* * *

Herbert Mayo was fired

by King’s College in 1836 for his poor teaching skills, though he went on to cofound the successful Middlesex Hospital anatomy school. By 1842 he was crippled by osteoarthritis and moved to the German spa town of Bad Weilbach, where he became increasingly mystical, publishing such works as

On the Truths Contained in Popular Superstitions

(1849). He was also intrigued by phrenology and physiognomy, and his medical writing now appeared to have more in common with the Tudor theory of the humors than with the brave new world of anatomy and physiology, in which latter field he had once been such a brilliant pioneer. Typical observations from Mayo’s later years were that sanguine people tend to have red hair and to respond well to being bled, that Italians are bilious or melancholic and have olive complexions, and that cards, angling, and chess are excellent defenses against insanity (from

The Philosophy of Living

, 1837). He died in a German hydropathic hotel in 1852.

Richard Partridge failed to fulfill his potential. Though he succeeded Mayo as King’s College’s professor of anatomy in 1836, he never ceased to be nervous as a surgeon and maintained a stolid, unremarkable role as teacher and anatomical draftsman. In 1862, he had the honor to inspect, before a number of onlookers, the injured foot of Italian patriot and freedom fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi. He failed to spot a bullet lodged in Garibaldi’s ankle; another surgeon approached and located and removed the bullet straightaway. Partridge’s reputation never recovered, and he died in poverty eleven years later.

While lecturing at King’s College, Partridge would tell his students the Bishop and Williams story, embellishing it with the fiction that the convictions had been secured when the New Police had placed cheese on the floor of 3 Nova Scotia Gardens and a number of little white mice had crept out of hiding to nibble it, thereby proving that the Italian boy had been killed in the house.

Thomas Williams was pledged to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital museum, though he does not appear in the nineteenth-century catalogs of that institution, and his whereabouts are unknown. The remains of John Bishop maintained a moderate profile for much of the century: his skeleton and the skin of his arms had pride of place in King’s College’s pathological museum for decades. In 1871, however, he was spotted in a private moneymaking concern, Dr. Kahn’s Anatomical Museum, near Leicester Square in the West End; either King’s had decided to sell their once-famous prize or Dr. Kahn was deceiving the public with an imitation John Bishop among his display of Siamese twin fetuses, harelips, hemorrhoids, hernias, “the dreadful effects of lacing stays too tightly,” plus plenty of oddly formed genitals, displayed “for medical gentlemen only.”

5

Richard Partridge’s disastrous examination of Garibaldi in 1862; the anatomist’s career did not recover.

But the London Burker has not taken up his rightful place in a glass cabinet alongside 1820s boxing promoter turned killer John Thurtell, the “Red Barn murderer” William Corder, and other long-forgotten villains in the Hunterian Museum in the Royal College of Surgeons, though it is possible that he was once there and that his remains perished in the same Luftwaffe direct hit that destroyed many items in the museum in May 1941, including the skeleton of Chunee the elephant and the (alleged) intestine of Napoleon Bonaparte.

* * *

So much for the actors;

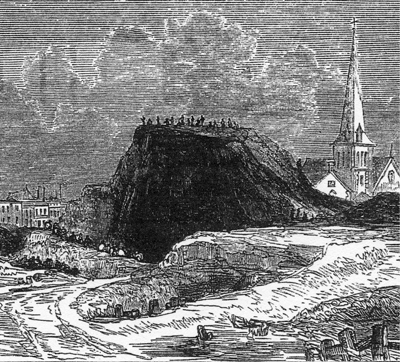

as for the location, Nova Scotia Gardens acquired a new sobriquet, Burkers Hole, by which it would be known for the next twenty-five years. A myth arose that the cottages communicated with one another via a warren of cellars and subterranean passages—a vivid image of how London’s criminal fraternity were felt to be able to move around unseen along secret pathways of their own making. In the 1840s Nova Scotia Gardens was one of the slums traversed by such sanitary reformers as George Godwin, Henry Austin (Charles Dickens’s brother-in-law), and Dr. Hector Gavin. Godwin, in 1859, decided that “an artistic traveller, looking at the huge mountain of refuse which had been collected, might have fancied that Arthur’s Seat at Edinburgh, or some other monster picturesque crag, had suddenly come into view, and the dense smell which hung over the ‘gardens’ would have aided in bringing ‘auld reekie’ strongly to the memory. At the time of our visit, the summit of the mount was thronged with various figures, which were seen in strong relief against the sky; and boys and girls were amusing themselves by running down and toiling up the least precipitous side of it. Near the base, a number of women were arranged in a row, sifting and sorting the various materials placed before them. The tenements were in a miserable condition. Typhus fever, we learnt from a medical officer, was a frequent visitor all round the spot.” “Refuse” was Godwin’s euphemism for human feces; Gavin described the same scene as “a table mountain of manure,” which towered over “a lake of more liquid dung.”

6

A refuse collector was using Nova Scotia Gardens as his official tip, accumulating this vast mound from which the still-destitute residents of that part of Bethnal Green came to salvage some sort of living. So much for the New Poor Law: people chose to live off, and play on, noxious rubbish tips rather than enter the workhouse.

Half a century later a nostalgia column, “Chapters of Old Shore-ditch,” in the local newspaper, the

Hackney Express and Shoreditch Observer,

featured an aged local resident’s eyewitness memory of “the fearful hovels … once so famous in the days of Burking,… a row of dilapidated old houses standing back from the line of frontage and in a hollow, with a strip of waste land in front, on which was laid out for sale flowers, greengrocery and old rubbish of all kinds”; the following week another contributor recalled “the antiquated property known as The Hackney Road Hollow.”

7

Royalty, too, came to gawk at the natives; Princess Mary Adelaide, duchess of Teck—granddaughter of George III and mother-in-law to the future George V—recalled of the Gardens: “There was a large piece of waste ground covered in places with foul, slimy-looking pools, amid which crowds of half-naked, barefooted, ragged children chased one another. From the centre arose a great black mound.… The stench continually issuing from the enormous mass of decaying matter was unendurable.”

8

But the most important visitor to these fetid regions was Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), heiress, philanthropist, baroness (from 1871), and, for two decades, close friend of Charles Dickens. Together, she and the novelist would take long night walks to some of the “vilest dens of London” during the 1840s and 1850s; and from time to time Nova Scotia Gardens, “the resort of murderers, thieves, the disreputable and abandoned,” featured on their East End itinerary, according to Mary Spencer-Warren, author of the only press interview that Burdett-Coutts ever gave.

9

Architectural/sanitary campaigner George Godwin discovered a mountain of rubbish and sewage when he visited Nova Scotia Gardens in 1859; this sketch appeared in his campaigning book

Town Swamps and Social Bridges.

No documentary evidence survives to reveal whether it was Dickens or Burdett-Coutts who first suggested Nova Scotia Gardens as a destination. But Burdett-Coutts’s link to Burkers Hole was striking indeed. Her grandfather Thomas Coutts, founder of the bank Coutts & Co., had died in 1822, leaving his £900,000 fortune to his second wife, actress Harriot Mellon, who, in 1827, married the duke of St. Albans and became even richer. Her mother dead, and with no close female relative, Angela spent weeks, even months, with her adored stepgrandmother in Harriot’s Highgate villa, Holly Lodge. Harriot, who was spoken of fondly by, among others, William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, and poet laureate Robert Southey, had a quick wit, a deep purse, and a very kind heart, perhaps too kind. “Her charities were abused and misapplied by too many of the thankless wretches who had partaken of her bounty,” according to one who knew her.

10

One of the many local people whom Harriot tried to help out, in 1816, was the pregnant young Highgate widow Sarah Bishop. It is known that at the time of the Bishop and Williams case, Angela, then seventeen, was living with Harriot; had she perhaps heard background details of the case from her sprightly hostess?