The Italian Boy (46 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Harriot died in August 1837 and left her fortune to twenty-three-year-old Angela. (She had intended to leave it to Lord Dudley Stuart, who, in 1834, had been so indignant when two Italian boys were arrested outside his home, but Harriot had cut him out of her will when he went against her advice and married the niece of Napoleon Bonaparte.) Possibly inspired by Harriot’s kindness, but determined to be more discriminating in her giving, Angela set out upon a lifetime of philanthropy, which she conducted according to both her religious principles and the dominant social ideals of the midcentury. Dickens, while their friendship endured, from 1839 to 1859, was to be one of her mentors as she struggled to transcend the limits of her outlook and experience.

In 1852, Angela bought Nova Scotia Gardens for £8,700. She intended to raze the cottages and in their place build salubrious homes that would lead to the moral, spiritual, and physical improvement of the dwellers of Burkers Hole. But she had not been informed that the refuse collector was legally entitled to stay on the land, no matter who owned it, and to use it as he saw fit until 1859. It was only in that year that she was able to set about her grand project. She employed architect Henry Darbishire to create Columbia Square, a magnificent five-story block of one-, two-, and three-room apartments, housing 180 families who paid the affordable sum of between 2s 6d and 5s a week in rent; there were shared washing facilities and WCs on each floor, and a library, club room, and play areas. Before long, there was a waiting list of families keen to move into the apartments.

Columbia Square was an odd amalgam of industrial-style tenements onto which were grafted Gothic Revival pinnacles and pointed arches; plain yellow stock bricks were dressed with portland stone and terra-cotta moldings. What followed next was even more exotic: Columbia Market, built just to the west of the square between 1863 and 1869, was a Castle Perilous extravaganza that included thirty-six shops and four hundred market stalls for local traders and produce sellers. It looked like a miniature cathedral and came complete with pieties painted on the walls, such as “Speak everyman truth unto his neighbour,” and orders forbidding swearing, drunkenness, and Sunday trading. It went bust within six months.

The baroness’s housing continued to be popular for nearly a hundred years, but Columbia Square was finally condemned as unfit for human habitation in the 1950s; the market died alongside it when Henry Darbishire’s masterpieces fell to the demolition ball in 1960. A local authority housing estate, still in use, was built on the site. The Birdcage pub opposite has watched all this, unscathed.

Philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts built Columbia Market

(

top

)

and Columbia Square on the site of Nova Scotia Gardens in the 1860s.

* * *

The Bishop and Williams case

itself began a slow decline into obscurity, a number of factors combining to push the London Burkers into the shadows. The “Asiatic cholera” had entered the country at Sunderland in August 1831; it reached London in February 1832 and by the summer had killed an estimated thirty-two thousand people in Britain, fifty-five hundred of them Londoners. The fear of urban miasma—the exhalations of graveyards and the stinking, sluggish air in courts, alleys, and warrens that were (mistakenly) blamed for the outbreak—quickly pushed “Burkiphoby” from its top billing. The bacillus cholera vibrio could kill within hours of being ingested in food or, more frequently, in drinking water, where it could live for up to a fortnight—all of which would remain unknown until the 1850s and not fully accepted by the medical community until the 1880s. A typhus epidemic struck London in 1837–38, while cholera revisited London in 1848–49 (killing fifteen thousand), 1853–54, and 1866–67. It was the air of London—its smells, mists, fogs, smoke—rather than its criminal element that held a mysterious terror for the city’s inhabitants and visitors in the 1830s.

Besides, Burke and Hare were continuing to do perfectly good duty as archetypal murderers for dissection. The story of the Edinburgh Horrors had charming, voluble Burke, hideous, cretinous Hare; sinister, proud Dr. Knox, pathetic Daft Jamie, and alluring Mary Paterson. And from the mid-1830s, a new era of complex and exciting murders was ushered in, reported by an increasingly sophisticated newspaper and periodical press that could now reproduce high-quality illustrations of scenes of crime and dramatis personae. An ever more literate population wanted to read about people of quality (professionals, many of them) murdering one another in drawing rooms, boudoirs, hotel rooms; they preferred their killers and victims to be able to express themselves at great length in letters; they wanted—and got—swindlers and frauds, adulterers and adulteresses; bigamists, usurped heirs, jealous spouses, all pursued, from August 1842, by the specialist Detective Branch of Scotland Yard, the first permanent plainclothes squad.

Bishop and Williams crop up toward the end of the century in George Eliot’s

Middlemarch

(1871–72), chapter 50, when the rector’s gossipy wife, Mrs. Cadwallader, says snobbishly of the book’s heroine, Dorothea Brooke, that she “might as well marry an Italian with white mice” as marry Will Ladislaw, and thereby lose her fortune.

Middlemarch

is set in 1829–32, and partly concerns the efforts of the idealistic young doctor Tertius Lydgate to found a new hospital in the town. Mrs. Cadwallader’s remark is a wholly contemporary reference to the London Burkers and to the scandal that doctors could find themselves linked to.

Before that, though, the killers had provided inspiration for one of the midcentury’s biggest-selling works of fiction. In 1844, journalist George William MacArthur Reynolds (1814–79), a bankrupt Radical and teetotaler, read an English translation of the French popular literary sensation

Les Mystères de Paris

(1842), written by Eugène Sue, and immediately hit on the idea of a British imitation. Reynolds’s

The Mysteries of London

was published between October 1844 and 1856 in weekly issues, at the low price of one pence to attract the working-class reader.

11

Those who were unable to afford a penny a week for fiction or who were illiterate could nevertheless enjoy the stories since literate members of the community would read aloud to groups of twelve or so in a tavern or some other public space. Reynolds’s tales are said to have outsold every other rival serial and novel, with thirty to forty thousand copies a week printed at the height of their popularity; in 1846, three different stage adaptations could be seen in London.

The Mysteries of London

is a vast, rambling series of interconnecting episodes in which two brothers, Richard Markham, the hero, and his dissolute brother, Eugene, the villain, endure various adventures. In the course of the plot, the misdeeds of a corrupt, enervated aristocratic elite are juxtaposed with the depredations of London’s underworld characters, and the most important of the latter, occupying the dark heart of the book, is the Resurrection Man.

The Resurrection Man lives in Bethnal Green, in a squalid, damp house that has an eight-room dungeon beneath it, accessed by the pull of a lever near the hearth. A small alley runs alongside the house, and late one night the Resurrection Man is observed with another man in the alley—they are dragging between them a blindfolded woman, who never emerges alive from the Resurrection Man’s cellar. His favorite drinking places are the Dark House at the northern end of Brick Lane (not far from Nova Scotia Gardens) and the Boozing Ken on Saffron Hill; he serves time in Coldbath Fields; he disinters a girl’s body from beneath the flagstones of Shoreditch Church.

The Mysteries

opens in July 1831—a very specific time, though its significance is not explained to the reader; perhaps it is coincidence, but this is the month in which Bishop and Williams first met. In the series’ opening scene, a youth becomes lost in the maze of alleys near the Fleet Ditch, then, trapped in a rotting hovel called “The Old House in Smithfield,” he is flung by two men through a trapdoor into a well that empties into the Fleet.

Though the Anatomy Act had finally killed off the trade by 1844, resurrection, it seems, remained a potent folk memory, a fact that Reynolds was keen to play on in his choice of bogeyman, who in the course of

The Mysteries

is stabbed, blown up, imprisoned, and left for dead on a plague ship but who nevertheless returns to stalk the hero of the book.

Reynolds’s story also cleverly capitalized on the deeper physical strata of London that were being unearthed in the mid-1840s, with the so-called Metropolitan Improvements—new roads, railway lines, bridges, tunnels, and the laying of drains. The discoveries made during these works revealed some uncanny facts about the old fabric of the city and fed into a particularly urban paranoia about subterranean spaces—the sort of anxiety that created the legend that Nova Scotia Gardens was sitting atop a warren of passages connecting the cottages. In 1837, a Parliamentary Select Committee convened to examine the feasibility of bricking over the Fleet River and converting it into a sewer revealed that the neighborhood of Saffron Hill, close to Smithfield, featured a great many manholes leading to shafts twenty to thirty feet deep into which a person could descend below the level of the street. These had never been properly mapped or charted before, and, along with the Fleet and its fetid tributaries, were being investigated as possible miasmatic sources of the cholera and typhus outbreaks.

12

In 1844, as part of these same belated improvements, Farringdon Road was built through the slums around the Fleet, and to the thrilling horror of nonlocals, the Old Red Lion Tavern at 3 West Street, Smithfield, was discovered to have been a warrenlike house, hollowed out and customized to hide booty and prisoners on the run; it featured secret passages, trapdoors, subterranean rooms, sliding panels, and escape routes into other houses or onto the slimy banks of the Fleet. The building dated back to 1683 and was also known locally as the Old House in West Street and Jonathan Wild’s House, after the notorious magistrate-cum-thief hanged in 1725. Sightseers paid to be taken on tours of the house and the remains of the semidemolished streets around Saffron Hill, Field Lane/West Street, Turnmill Street, Cowcross. A similarly uncanny honeycomb of rotting old houses and convoluted streets was discovered in the same year when St. Giles, near Covent Garden, was razed for the building of New Oxford Street and, in the following year, when Victoria Street was constructed through the Devil’s Acre slums in Westminster.

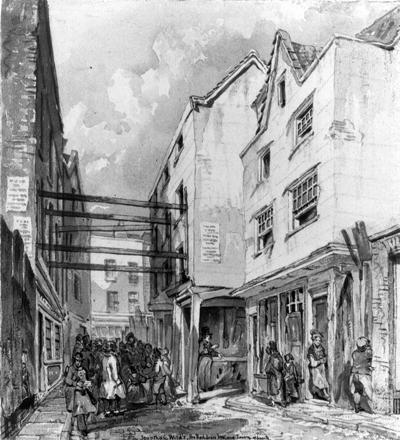

In 1844, sightseers lined up to visit the soon to be demolished Old Red Lion Tavern in Smithfield

(

above

)

and its warren of passages and hidden chambers. It had been built on the banks of the filthy Fleet, from which people scavenged a living (overleaf, top

)

and above which were cheap lodging houses for the poor (overleaf, bottom).