The Jefferson Lies (21 page)

Why was Jefferson such a faithful participant at the Capitol church? He once explained to a friend while they were walking to church together:

No nation has ever yet existed or been governed without religionânor can be. The Christian religion is the best religion that has been given to man and I, as Chief Magistrate of this nation, am bound to give it the sanction of my example.

102

135

By 1867 the church in the Capitol had become the largest church in Washington.

103

Other presidential actions of Jefferson include:

⢠Urging the commissioners of the District of Columbia to sell land for the construction of a Roman Catholic Church, recognizing “the advantages of every kind which it would promise” (1801)

104

⢠Writing a letter to Constitution signer and penman Gouverneur Morris (then serving as a US senator) describing America as a Christian nation, telling him that “we are already about the 7th of the Christian nations in population, but holding a higher place in substantial abilities” (1801)

105

⢠Signing federal acts setting aside government lands so that missionaries might be assisted in “propagating the Gospel” among the Indians (1802, and again in 1803 and 1804)

106

⢠Directing the secretary of war to give federal funds to a religious school established for Cherokees in Tennessee (1803)

107

⢠Negotiating and signing a treaty with the Kaskaskia Indians that directly funded Christian missionaries and provided federal funding to help erect a church building in which they might worship (1803)

108

⢠Assuring a Christian school in the newly purchased Louisiana Territory that it would enjoy “the patronage of the government” (1804)

109

136

⢠Renegotiating and deleting from a lengthy clause in the 1797 United States treaty with Tripoli

110

the portion that had stated “the United States is in no sense founded on the Christian religion” (1805)

111

⢠Passing “An Act for Establishing the Government of the Armies” in which:

It is earnestly recommended to all officers and soldiers diligently to attend Divine service; and all officers who shall behave indecently or irreverently at any place of Divine worship shall, if commissioned officers, be brought before a general court martial, there to be publicly and severely

reprimanded by the President

[Jefferson]; if non-commissioned officers or soldiers, every person so offending shall [be fined]

112

(1806) (emphasis added)

⢠Declaring that religion is “deemed in other countries incompatible with good government, and yet proved by our experience to be its best support”

113

(1807)

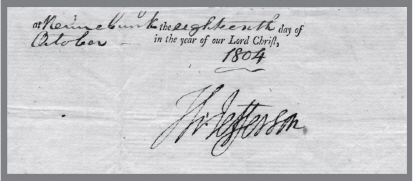

⢠Closing presidential documents with the appellation, “In the year of our Lord Christ”

114

(1801â1809; see inset)

137

There are many additional examples, and they all clearly demonstrate that Jefferson has

no

record of attempting to secularize the public square. Furthermore, all of his religious activities at the federal level occurred after the First Amendment had been adopted, showing that he saw no violation of the First Amendment in any of his actions. In fact, no one didânot even his enemies. No one ever raised a voice of dissent against Jefferson's federal religious practices; no one claimed that they were improper or that they violated the Constitution.

The only voice of objection ever raised was to complain that President Jefferson, unlike his predecessors George Washington and John Adams, did not issue any national prayer proclamations. This absence of a national prayer proclamation by Jefferson is cited by critics today as definitive proof of Jefferson's public secularism.

For example, Supreme Court Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall noted in

Marsh v. Chambers

that:

Thomas Jefferson . . . during [his] respective terms as President, refused on Establishment Clause [First Amendment] grounds to declare national days of thanksgiving or fasting.

115

Justice Anthony Kennedy similarly noted in

Allegheny v. ACLU

:

In keeping with his strict views of the degree of separation mandated by the Establishment Clause, Thomas Jefferson declined to follow this tradition [of issuing national proclamations].

116

Yet these justices are completely wrong. Jefferson himself pointedly stated that his refusal to issue national prayer proclamations was not because of any First Amendment scruples about religion but rather because of his specific views of Federalismâthat the Constitution specifically limited the federal government but not the states or other government entities. He explained:

138

I consider the government of the United States [the federal government] as interdicted [prohibited] by the Constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises. This results not only from the provision that “no law shall be made respecting the establishment or free exercise of religion” [the First Amendment], but from that also which reserves to the states the powers not delegated to the United States [the Tenth Amendment]. Certainly, no power to prescribe any religious exercise or to assume authority in religious discipline has been delegated to the general [federal] government. It must then rest with the states, as far as it can be in any human authority. But it is only proposed that I should

recommend

, not prescribe [require] a day of fasting and prayer. . . . I am aware that the practice of my predecessors may be quoted. But I have ever believed that the example of state executives [governors issuing prayer proclamations] led to the assumption of that authority by the general government [the president issuing prayer proclamations] without due examination, which would have discovered that what might be a right in a state government was a violation of that right when assumed by another.

117

Jefferson made very clear that his refusal to issue federal prayer proclamations did not spring from any concerns over religious expressions in general but rather only from his view of federalism and which was the proper governmental jurisdiction. He believed that there was a limitation on the federal government's ability to direct the states in which religious activities they could or should participate in, but he saw no such limitations on state or local governments. Actively encouraging public religious activities for citizens was well within their jurisdiction and completely appropriate and constitutional.

Because of his understanding of federalism, Jefferson refused to issue a presidential call for prayer, but he had certainly done so as a state leader. In addition to his 1774 Virginia legislative call for prayer,

118

he called his fellow Virginians to a time of prayer and thanksgiving while serving as governor in 1779, asking the people to give thanks “that He hath diffused the glorious light of the Gospel, whereby through the merits of our gracious Redeemer we may become the heirs of the eternal glory.”

119

139

He also asked Virginians to pray “that He would grant to His church the plentiful effusions of Divine grace and pour out his Holy Spirit on all ministers on the Gospel; that He would bless and prosper the means of education and spread the light of Christian knowledge through the remotest corners of the earth.”

120

And Jefferson had personally penned the state bill “Appointing Days of Public Fasting and Thanksgiving.” He clearly was not opposed to official prayer proclamations, but he believed that this function was within the jurisdiction of governors, not presidents. Certainly, presidents before and after Jefferson did not agree with this view and regularly issued federal prayer proclamations, but the evidence shows that Jefferson's refusal to do so was not because of any notion of secularism on his part but rather because of his view of federalism.

Jefferson's record of including, advocating, and promoting religious activities and expressions in public is strong, clear, and consistent. He did not support a secular public square. The institutional separation of Church and State so highly praised by today's civil libertarians did not originate from Jefferson or even from secularistsânor did it have societal secularization as its object. To the contrary, it was the product of Bible teachings and Christian ministers. Its object was the protection of religious activities and expressions whether in public or private.

140

Jefferson's words and actions unequivocally demonstrate that he was not “a secular humanist,”

121

nor did he in any manner seek to secularize the public square. This is simply another of the many modern Jefferson lies that has no basis in history.

141

L

IE

# 6

Thomas Jefferson Detested the Clergy

S

ome claim that Jefferson had a dislike of Christian clergy and that this dislike was yet one more manifestation of his overall hostility to religion. They say:

[H]e detested the entire clergy, regarding them as a worthless class living like parasites upon the labors of others.

1

Thomas Jefferson, in fact, was fiercely anti-cleric.

2

“The clergy” were one of his enemies who were trying to keep him from being elected President. Surely they would have wanted a devout, God-fearing Christian to be elected! So this is one more proof of Jefferson's religious beliefs.

3

Some of the Framers of the Constitution were anti-clericalâThomas Jefferson, for example.

4

By now, we have covered enough original source material from Jefferson to make these claims laughably, obviously incorrect. But let us proceed to put the final nails in the coffin of this lie and lay it permanently to rest. Of course, as noted in the last chapter, with the fact that Jefferson was

not

a framer of the Constitution despite what writers such as Austin Cline, the author of the latter quote and a leader in prominent secularist groups, continue wrongly to assert. But notwithstanding that glaring historical inaccuracy, was Jefferson indeed anticlerical?

142

To unequivocally put this question to bed, it is important to place Jefferson within his own time rather than that of today, avoiding the mistakes that occur when Modernism is applied to historical inquiry.

Throughout the Colonial, Revolutionary, and early Federal periods, organized political parties were nonexistent. The people were divided as Whigs and Tories, Patriots and Loyalists, Monarchists and Republicans, but there was no political party affiliation. This changed during the administration of President George Washington. Widely differing viewpoints on the scope and power of the federal government emerged among his leadership. Individuals such as Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Vice President John Adams sought for increased federal power, while others, such as Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Attorney General Edmund Jennings Randolph, sought for limited federal power.

Those led by Adams and Hamilton coalesced into what became known as the Federalist Party; those led by Jefferson coalesced into the Anti-Federalist Party. Anti-Federalists were also known as Republicans and then as Democratic-Republicans; by the time of Andrew Jackson, they had become the Democrats. The Northern colonies and New England provided the strongest base of support for the Federalists while the strength of the Anti-Federalists was from Pennsylvania southward. The Federalists tended to be stronger in populous areas already accustomed to more government at numerous levels. The Anti-Federalists were generally stronger in rural areas where people were more lightly governed.

Jefferson observed that those in the Northern regions had many good traits; they were “cool, sober, laborious, persevering . . . jealous of their own liberties and just to those of others” while those in the south had many negative traits, including being “voluptuary, indolent, unsteady, . . . zealous for their own liberties but trampling on those of others.”

5

But Jefferson saw the religious characteristics of the two regions as generally reversed: “[I]n the north they are . . . chicaning, superstitious, and hypocritical in their religion” while “in the south they are . . . candid, without attachment or pretentions to any religion but that of the heart.”

6

Religion was definitely important in all regions of early America, but as Jefferson noted, there was indeed a clear difference in the way it was practiced in Federalist and Anti-Federalist regions.