The Kennedy Half-Century (84 page)

Read The Kennedy Half-Century Online

Authors: Larry J. Sabato

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Modern, #20th Century

Thus, it is easy to comprehend why almost every Democratic candidate for president since JFK has been analyzed through the lens of Kennedy. The more fluent contenders try to be Kennedy, and the press often confers the title of pretender for a few months. Reality eventually sets in, however. No flesh-and-blood politician can compete with the larger-than-life monument that is John Kennedy. For Democrats, he was long ago elevated to Mount Rushmore. For Democratic

and

Republican presidents, Kennedy has presented a different challenge. They cannot vie with an apparition. Yet JFK’s more clever White House successors have been able to create opportunities for themselves using Kennedy’s record. Lyndon Johnson showed the way, but Ronald Reagan was just as skillful and successful, all the more because he had to wave the Kennedy standard to win Democratic support without alienating his own Republicans. Bill Clinton and Barack Obama each ran for the White House as the semiofficial New Kennedy; it worked well on the campaign trail but less well in office, since the press and public eventually discovered that Clinton and Obama were not Kennedy. Jimmy Carter became the un-Kennedy, a precarious posture for a Democrat, and his fate in 1980 proved it. All of Kennedy’s successors learned to selectively employ, or at least tread carefully around, JFK’s legacy. As our public poll demonstrated, Kennedy has remained an idol unequaled by any of them, save perhaps Reagan. In many ways, Kennedy’s cult of personality is as strong today as in the 1960s, when the memory of his presidency was fresh and universal.

Only the terminally starry-eyed still see John F. Kennedy as an ideological crusader, drawn to politics by idealistic fervor about the great issues of the day. Unlike his brother Bobby in the last years of his life, or youngest brother Ted during many of his decades in the Senate, liberalism had little to do with John Kennedy’s motives. The long view of JFK’s career reveals that he was eager to define himself as more anticommunist, pro-defense, anticrime, probusiness, and cautious on civil rights than many of his contemporaries in

both parties. John Kennedy was no leftist; he placed himself squarely in the mainstream of the Democratic Party and the country during his seventeen-year political sojourn.

Burning ambition, transferred by his father’s desires from his deceased older brother Joe, was at JFK’s core. The Democratic Party and its constituencies were mere instruments in the march to power. Platform planks were walking sticks used to climb the mountain. The New Frontier was no grand governing philosophy, but a piecemeal accumulation of ideas and opportunities that gradually evolved during Kennedy’s campaign and presidency. Interestingly, that pragmatism has permitted John Kennedy to become an icon for modern-day Democrats and Republicans alike. His bifurcated philosophy, partly left and partly right (in today’s ideological terms), enables Democrats to make civil rights and peace his monument while Republicans herald his tax cuts, muscular foreign policy, and space program.

Kennedy could not have foreseen this, nor was it his motivation. JFK and his entire family were drawn to the exercise of raw power, the perfect accompaniment to their colossal wealth. They were driven by desire for the ultimate clout of the White House, determined to be in the king’s castle at the top of that shining city on a hill. Is this really any different from the incentives that have attracted most other men to seek and win the presidency before and after Kennedy? They surfed the waves of public opinion and did what was necessary to grasp the magnificent prize, but always, at the heart of it, they wanted to possess ultimate command and control over others. What sets the Kennedys apart is that never—at least until the Bushes—has a large family acted as one single-minded, unstoppable organism that methodically sought and won the highest office.

For the Kennedys, if there was a subterranean impulse beyond the overriding wish to be in charge, it might have been to achieve domination over the Anglo-Saxon Protestants who had run things for centuries and turned their noses up at Irish Catholic immigrants. It was delicious turnabout that the WASPs would have to come hat in hand to an Irish Catholic clan and beg for favors WASPs had considered their birthright. Anyone who has ever fought an arrogant in-crowd can appreciate it—but sweet revenge is not normally the stuff of heroic legend.

The legend derives instead from sorrow. In the aftermath of JFK’s assassination, all things Kennedy were sanctified. Five decades on, that is no longer true, but a transformed Kennedy legacy lives. It certainly is not the one forged in JFK’s exciting but vapid 1960 campaign, which in most ways (the new television debates aside) was quite conventional. Like all campaigns it was characterized by exaggerated attacks about minor matters, revolving more around style than substance. Not a sentence from the Kennedy-Nixon

debates has lived on, because nothing weighty was uttered in those hours on the air. We recall what Americans watching then perceived. Kennedy looked terrific: movie-star handsome, tanned, and forceful. This is especially remarkable since throughout the campaign his image makers projected youthful vigor in a chronically ill man, not to mention the phony idealization of a secretly dysfunctional marriage. The election of 1960 was not a realigning watershed that set the nation’s path going forward, but a narrow tactical victory about little. Regrettably, the Kennedy-Nixon campaign was one of many “Seinfeld elections” in U.S. history—a contest about nothing beyond partisan and tribal loyalties in which the real challenges facing the winner are never much discussed. The 1960 match-up is remembered mainly because it was astonishingly close and JFK managed to break the religious barrier.

Nor is President Kennedy’s legacy one of historic achievement in the Oval Office. The seventh-shortest presidency, JFK’s time in the White House was too brief for a lengthy list of accomplishments.

3

This recalls Kennedy’s litany of reasons about why “life isn’t fair” at one of his presidential press conferences.

4

The general principle JFK cited could well apply to the reality that an assassin’s bullet deprived him of five more years at the helm to make his full mark in history. The inequity of this does not reduce its harsh effect on an evaluation of Kennedy’s presidency: There is simply much less in Kennedy’s White House record than there might have been for us to judge.

In the sweep of history, nothing JFK attained will matter more than his daring bet on NASA and a moon landing, which has permanently expanded man’s horizons and led to earthbound breakthroughs in science, technology, communications, medicine, and consumer products of all sorts. Humankind’s millennia of space exploration to come will always trace its roots to JFK’s bold 1961 declaration of intent.

Kennedy also displayed critical growth in the presidency in two areas that changed the course of America. JFK was not especially sensitive to the plight of African Americans at the outset of his term, and he took far too long to make civil rights a central goal. But once he did so in 1963, Kennedy set the stage for the second Reconstruction that delivered the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and a far more just society.

Just as important, the bellicose Kennedy of the inauguration gave way to a serious search for peace and common ground with the Communist world. Some say that Kennedy’s ineffective failures at the Bay of Pigs, in Berlin, and in early negotiations with the Soviet Union contributed to the near-fatal superpower encounter over Cuba in 1962. However, as Ted Sorensen insisted, “Every generation needs to know that without JFK the world might no longer exist as a result of a nuclear holocaust stemming from the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

5

That searing experience turned Kennedy, and probably the Russians,

away from sole reliance on tough rhetoric and military might and toward treaties, détente, and a lessening of international conflict where it was possible. This is a considerable legacy.

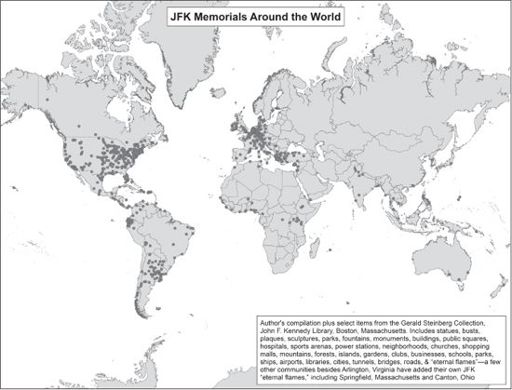

Without question, much of the globe has recognized Kennedy’s achievements on the world stage in concrete ways. In the United States and around the world, some thirteen hundred JFK memorials have been erected. While this is almost certainly a partial list, this too is the Kennedy legacy accumulated over a half century.

Kennedy’s place in the pantheon of presidencies should not be exaggerated. The great conflicts of his time were critically important, but many have faded in relevance and have as little connection to modern existence as the debate about tariffs in the nineteenth century. The Soviet Union no longer exists. The Cold War and its relatively tidy bipolar system have dissolved into a shadowy world of terrorist threats and transnational forces. The United States is no longer the undisputed economic giant of the 1960s that can dictate to other nations; the American century may well be ebbing as China, India, and other countries outstrip the United States in critical ways. The

Democratic Party of Kennedy’s time was overwhelmingly male, very substantially white, and dependent upon a segregationist South. That monochromatic status quo is a dinosaur in our century’s rainbow reality.

Just as outdated is Kennedy’s predatory personal behavior. It was as unrestrained and irresponsible as any ever engaged in by an occupant of the White House. The potential for extortion by Kennedy’s domestic and foreign enemies was huge, as was the risk of exposure, which would have destroyed his presidency as well as the dreams of his family and supporters.

6

His jawdropping escapades and libertine practices were in complete contradiction to the image he and his handlers projected of the devout Catholic and consummate family man. Had a single one of his dalliances become public, history would have recorded that John Kennedy and not Richard Nixon was the first president to resign in disgrace. In sexual matters, Kennedy’s self-control was nonexistent, and virtually on a daily basis, he risked everything. In addition, Kennedy’s successful attempt to hide the fragile state of his health and his use of potent, mind-distorting drugs on a regular basis, with the help of accommodating medical personnel, was an equal deception of the public. We ought to remember this because it is a cautionary tale. Americans in any century can be too inclined to accept consultant-crafted images of flesh-and-blood people. Just as important, the courtiers of the powerful, including many in journalism, can conspire to deceive us, or acquiesce in the deception, as they did with JFK.

This is the underbelly of JFK’s legacy. Standards for personal behavior and disclosure were far different in the 1960s than today. That fact does not absolve John Kennedy, but it does explain the mental process that enabled him to justify his conduct to himself and others.

Why, then, do so many Americans pine for the Kennedy era? Why is John Kennedy consistently rated one of the nation’s best presidents? Why have JFK’s successors so often sought to wear his mantle? Style and tragedy are the answers.

There will probably never be a more attractive couple in the White House than Jack and Jackie Kennedy. Their good looks and fashion sense transcended time; they could walk down the street today and not just fit in but command notice. JFK’s oratory was often so powerful that it was hypnotic. Compared to most politicians of his time and ours, Kennedy could have read the telephone directory and held our attention. Even to their political opponents, President and Mrs. Kennedy were the precise image America wanted to project to the world: youth, vitality, charm, wit, optimism, confidence, fearlessness about the future. Kennedy benefited from serving at a time when citizens still trusted their government, and his infectious enthusiasm and big-picture worldview made people, especially the young, want

to participate in remaking the world. The Peace Corps is only the most obvious example.

JFK’s apparent personification of the nation’s best qualities made November 22 all the more incomprehensible. At least during the lifetime of Americans who personally remember the assassination, the Kennedy legacy will remain vivid and indestructible. Mrs. Kennedy’s postassassination creation of Camelot was a brilliant fiction, but we were ready to believe it. We wanted a larger-than-life myth, and Camelot gave us a happier story to summon up and heroic possibilities to realize. Those who loved John Kennedy—his powerful family and influential supporters such as Arthur Schlesinger and Ted Sorensen—were determined that his life’s work would continue so his death would not be in vain, and they nurtured and extended the legend that Jackie built.

These efforts mattered because Kennedy’s death gave life to all the promises that might have remained unfulfilled had Kennedy served a second term. Even with a solid 1964 reelection victory, JFK would probably not have swept into power a Congress willing to enact the kind of controversial civil rights, antipoverty, and health care policies that were irresistible only as a tribute to an assassinated president. Had Kennedy been on the ballot in 1964, his margin over Barry Goldwater probably would not have been as great as that achieved by his successor, who capitalized on the nation’s remorse and grief over JFK’s murder. For Kennedy, Democratic legislative majorities would have been less swollen, and the public’s eagerness to erect legal monuments to a fallen leader would not have been a factor.