The King of Ireland's Son, Illustrated Edition (Yesterday's Classics) (6 page)

Read The King of Ireland's Son, Illustrated Edition (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Padraic Colum

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

He mounted and seeing his hound at his heel and his hawk circling above he felt a longing to go back to his father's Castle which he knew to be near and where he might find out where the King of the Land of Mist had his dominion.

So the King of Ireland's Son rode back to his father's Castle—

His hound at his heel,

His hawk on his wrist.

I

T

HE

King of Ireland's Son was home again, but as he kept asking about a King and a Kingdom no one had ever heard of, people thought he had lost his wits in his search for the Enchanter of the Black Back-Lands. He rode abroad every day to ask strangers if they knew where the King of the Land of Mist had his dominion and he came back to his father's every night in the hope that one would be at the Castle who could tell him where the place that he sought was. Maravaun wanted to relate to him fables from "The Breastplate of Instruction" but the King's Son did not hear a word that Maravaun said. After a while he listened to the things that Art, the King's Steward, related to him, for it was Art who had shown the King's Son the leaden ring that was on his finger. He took it off, remembering the betrothal ring that the Little Sage had made, and then he saw that it was not his, but Fedelma's ring that he wore. Then he felt as if Fedelma had sent a message to him, and he was less wild in his thoughts.

Afterwards, in the evenings, when he came back from his ridings, he would cross the meadows with Art, the King's Steward, or would stand with him while the herdsmen drove the cattle into the byres. Then he would listen to what Art related to him. And one evening he heard Art say, "The most remarkable event that happened was the coming into this land of the King of the Cats."

"I will listen to what you tell me about it," said the King's Son.

"Then," said Art, the King's Steward, "to your father's Son in all truth be it told"—

T

HE

King of the Cats stood up. He was a grand creature. His body was brown and striped across as if one had burned on wood with a hot poker. Like all the race of the Royal Cats of the Isle of Man he was without a tail. But he had extraordinarily fine whiskers. They went each side of his face to the length of a dinner-dish. He had such eyes that when he turned one of them upward the bird that was flying across dropped from the sky. And when he turned the other one down he could make a hole in the floor.

He lived in the Isle of Man. Once he had been King of the Cats of Ireland and Britain, of Norway and Denmark, and the whole Northern and Western World. But after the Norsemen won in the wars the Cats of Norway and Britain swore by Thor and Odin that they would give him no more allegiance. So for a hundred years and a day he had got allegiance only from the Cats of the Western World; that is, from Ireland and the Islands beyond.

The tribute he received was still worth having. In May he was sent a boatful of herring. In August he was let have two boatfuls of mackerel. In November he was given five barrels of preserved mice. At other seasons he had for his tribute one out of every hundred birds that flew across the Island on their way to Ireland—tomtits, pee-wits, linnets, siskins, starlings, martins, wrens and tender young barn owls. He was also sent the following as marks of allegiance and respect: a salmon, to show his dominion over the rivers; the skin of a marten to show his dominion in the woods; a live cricket to show his dominion in the houses of men; the horn of a cow, to show his right to a portion of the milk produced in the Western World.

B

UT

the tribute from the Western World became smaller and smaller. One year the boat did not come with the herring. Mackerel was sent to him afterwards but he knew it was sent to him because so much was being taken out of the sea that the farmer-men were plowing their mackerel-catches into the land to make their crops grow. Then a year came when he got neither the salmon nor the marten skin, neither the live cricket nor the cow's horn. Then he got righteously and royally indignant. He stood up on his four paws on the floor of his palace, and declared to his wife that he himself was going to Ireland to know what prevented the sending of his lawful tribute to him. He called for his Prime Minister then and said, "Prepare for Us our Speech from the Throne."

The Prime Minister went to the Parliament House and wrote down "Oyez, Oyez, Oyez!" But he could not remember any more of the ancient language in which the speeches from the Throne were always written. He went home and hanged himself with a measure of tape and his wife buried the body under the hearth-stone.

"Speech or no speech," said the King of the Cats, "I'm going to pay a royal visit to my subjects in Ireland."

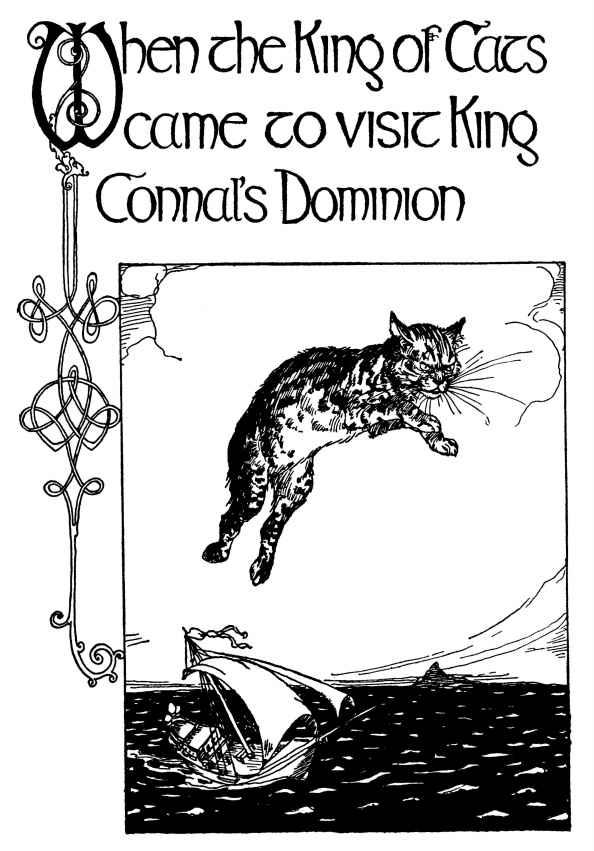

He went to the top of the cliff and he made a spring. He landed on the deck of a ship that was bringing the King of Norway's daughter to be married to the King of Scotland's son. The ship nearly sank with the crash of his body on it. He ran up the sails and placed himself on the mast of the ship. There he gathered his feet together and made another spring. This time he landed on a boat that was bringing oak-timber to build a King's Palace in London. He stood where the timber was highest and made another spring. This time he landed on the Giant's Causeway that runs from Ireland out into the sea. He picked his steps from boulder to boulder, and then walked royally and resolutely on the ground of Ireland. A man was riding on horseback with a woman seated on the saddle behind him. The King of the Cats waited until they came up.

"My good man," said he very grandly, "when you go back to your house, tell the ash-covered cat in the corner that the King of the Cats has come to Ireland to see him."

His manner was so grand that the man took off his hat and the woman made a courtesy. Then the King of the Cats sprang into the branch of a tree of the forest and slept till it was past the mid-day heat.

I nearly forgot to tell you that as he slept on the branch his whiskers stood around his face the breadth of a dinner-dish either way.

T

HE

next day the King's Son rode abroad and where he went that day he saw no man nor woman nor living creature in the land around. But coming back he saw a falcon sailing in the air above. He rode on and the falcon sailed above, never rising high in the air, and never swooping down. The King's Son fitted an arrow to his bow and shot at the falcon. Immediately it rose in the air and flew swiftly away, but a feather from it fell before him. The King's Son picked the feather up. It was a blue feather. Then the King's Son thought of Fedelma's falcon—of the bird that flew above them when they rode across the Meadows of Brightness. It might be Fedelma's falcon, the one he had shot at, and it might have come to show him the way to the Land of Mist. But the falcon was not to be seen now.

He did not go amongst the strangers in his father's Castle that evening; but he stood with Art who was watching the herdsmen drive the cattle into the byres. And Art after a while said, "I will tell you more about the coming of the King of the Cats into King Connal's Dominion. And as before I say

"To your father's Son in all truth be it told"—

T

HE

King of the Cats waited on the branch of the tree until the moon was in the sky like a roast duck on a dish of gold, and still neither retainer, vassal nor subject came to do him service. He was vexed, I tell you, at the want of respect shown him.

This was the reason why none of his subjects came to him for such a long time: The man and woman he had spoken to went into their house and did not say a word about the King of the Cats until they had eaten their supper. Then when the man had smoked his second pipe, he said to the woman:

"That was a wonderful thing that happened to us to-day. A cat to walk up to two Christians and say to them, 'Tell the ashy pet in your chimney corner at home that the King of the Cats has come to see him.' "

No sooner were the words said than the lean, gray, ash-covered cat that lay on the hearthstone sprang on the back of the man's chair.

"I will say this," said the man; "it's a bad time when two Christians like ourselves are stopped on their way back from the market and ordered—ordered, no less—to give a message to one's own cat lying on one's own hearthstone."

"By my fur and claws, you're a long time coming to his message," said the cat on the back of the chair; "what was it, anyway?"

"The King of the Cats has come to Ireland to see you," said the man, very much surprised.

"It's a wonder you told it at all," said the cat, going to the door. "And where did you see His Majesty?"

"You shouldn't have spoken," said the man's wife.

"And how did I know a cat could understand?" said the man.

"When you have done talking amongst yourselves," said the cat, "would you tell me where you met His Majesty?"

"Nothing will I tell you," said the man, "until I hear your own name from you."

"My name," said the cat, "is Quick-to-Grab, and well you should know it."

"Not a word will we tell you," said the woman, "until we hear what the King of the Cats is doing in Ireland. Is he bringing wars and rebellions into the country?"

"Wars and rebellions,—no, ma'am," said Quick-to-Grab, "but deliverance from oppression. Why are the cats of the country lean and lazy and covered with ashes? It is because the cat that goes outside the house in the sunlight, to hunt or to play, is made to suffer with the loss of an eye."

"And who makes them suffer with the loss of an eye?" said the woman.

"One whose reign is nearly over now," said Quick-to-Grab. "But tell me where you saw His Majesty?"

"No," said the man.

"No," said the woman, "for we don't like your impertinence. Back with you to the hearthstone, and watch the mouse-hole for us."

Quick-to-Grab walked straight out of the door.

"May no prosperity come to this house," said he, "for denying me when I asked where the King of the Cats was pleased to speak to you."

But he put his ear to the door when he went outside and he heard the woman say,—

"The horse will tell him that we saw the King of the Cats a mile this side of the Giant's Causeway."

(That was a mistake. The horse could not have told it at all, because horses never know the language that is spoken in houses—only cats know it fully and dogs know a little of it.)

Q

UICK-TO-GRAB

now knew where the King of the Cats might be found. He went creeping by hedges, loping across fields, bounding through woods, until he came under the branch in the forest where the King of the Cats rested, his whiskers standing round his face the breadth of a dinner-dish.

When he came under the branch Quick-to-Grab mewed a little in Egyptian, which is the ceremonial language of the Cats. The King of the Cats came to the end of the branch.

"Who are you, vassal?" said he in Phœnician.

"A humble retainer of my lord," said Quick-to-Grab in High-Pictish (this is a language very suitable to cats but it is only their historians who now use it).

They continued their conversation in Irish.

"What sign shall I show the others that will make them know you are the King of the Cats?" said Quick-to-Grab.

The King of the Cats chased up the tree and pulled down heavy branches. "There is a sign of my royal prowess," said he.

"It's a good sign," said Quick-to-Grab.

They were about to talk again when Quick-to-Grab put down his tail and ran up another tree greatly frightened.

"What ails you?" said the King of the Cats. "Can you not stay still while you are speaking to your lord and master?"

"Old-fellow Badger is coming this way," said Quick-to-Grab, "and when he puts his teeth in one he never lets go."

Without saying a word the King of the Cats jumped down from the tree. Old-fellow Badger was coming through the glade. When he saw the King of the Cats crouching there he stopped and bared his terrible teeth. The King of the Cats bent himself to spring. Then Old-fellow Badger turned round and went lumbering back.

"Oh, by my claws and fur," said Quick-to-Grab, "you are the real King of the Cats. Let me be your Councillor. Let me advise your Majesty in the times that will be so difficult for your subjects and yourself. Know that the Cats of Ireland are impoverished and oppressed. They are under a terrible tyranny."

"Who oppresses my vassals, retainers and subjects?" said the King of the Cats.

"The Eagle-Emperor. He has made a law that no cat may leave a man's house as long as the birds (he makes an exception in the case of owls) have any business abroad."

"I will tear him to pieces," said the King of the Cats. "How can I reach him?"

"No cat has thought of reaching him," said Quick-to-Grab, "they only think of keeping out of his way. Now let me advise your Majesty. None of our enemies must know that you have come into this country. You must appear as a common cat."

"What, me?" said the King of the Cats.

"Yes, your Majesty, for the sake of the deliverance of your subjects you will have to appear as a common cat."