The King of Vodka (27 page)

Authors: Linda Himelstein

Â

C

ONTRASTING

M

OSCOW WITH

St. Petersburg in the early 1900s was a bit like describing the difference between cotton and silk. One was an invaluable essential, a durable and workmanlike staple. The other was more precious, a sumptuous, fragile, and somewhat elusive luxury. Vladimir had always seemed drawn to the latter.

Free of any obligation to the vodka business, he had begun to spend more time in St. Petersburg in the years after the 1905 revolution. Previously a frequent visitor to the city, Vladimir had taken in the theater, eaten in the finest restaurants, and mingled with the aristocracy, which had historically congregated more in St. Petersburg than in Moscow. But now, Vladimir sought something new. Following the sale of his shares in the family enterprise, the personal attacks he endured after

Bloody Sunday, and the anti-alcohol sentiment raging throughout the empire, he yearned for a fresh start. He had more than enough money and could pursue his love of the arts, particularly theater, with renewed vigor. In St. Petersburg, Vladimir could reinvent himself.

His attachment to the tsar's hometown stemmed in part from a stud farm he purchased there, where, in addition to his stallions, mares, and colts, he kept the offspring of his prized thoroughbred Pylyuga, the trotters Valentinochka and Piontkovskaya, named after the popular operetta star Valentina Piontkovskaya.

15

Vladimir had met the singer, most likely at one of her performances or at one of the many theater parties they both attended. She mesmerized him. Valentina's dark eyes were expressive and memorable because they shone in the same way diamonds do, changing their sparkle and brightness with the slightest shift in her gaze. Her thick, dark mop of hair was often pinned back by a jeweled clasp or hidden under an elaborate, feathered hat. Valentina carried herself like a queen, dressing in the most splendid gowns and furs, set off by expensive necklaces perfectly draped across her neckline. She was, in a word, dazzling. Grigoriy Yaron, the son of a well-known director, actor, and writer of operettas, was also an admirer. He wrote that Valentina was “amazingly graceful so that you started to want to paint her every movement, her every pose.”

16

Her charisma came through as much on the stage as it did off. Theater critics referred to Valentina as a superstar, an actress who possessed a trifecta of artistic gifts. She could sing, dance, and act. Polish by birth, she studied her craft in Italy and performed in cities throughout the Russian Empire. She landed the lead role in the St. Petersburg production of Franz Lehar's

The Merry Widow

, one of the most beloved operettas of the day. She also adored men, especially rich men.

That was where Vladimir had his advantage, for she offered him exactly what he craved. As a starlet, she was invited to the

most exclusive parties, and her social circle included an array of top Russian artists and actors. She reveled in the same ultraluxurious living as Vladimir did. He was also ideal for her, a dashing escort with seemingly infinite resources. As was the custom, he could be her lover and patron, underwriting her productions and funding the purchase of all the glamorous accessories necessary to maintain her highly cultivated public profile. “Diamonds and precious stones in general were something very peculiar to operetta actresses before the revolution [of 1917]. The quantity, quality and size of the diamonds were parameters used to judge the significance of a prima donna,” wrote one contemporary. “It became clear that along with high salaries, actresses needed to find other sources of income. These sources of income were found in the faces of admirers who sometimes spent enormous amounts of money for their objects of adoration.”

17

In no time at all, Vladimir and Valentina began living together in Vladimir's spacious apartment in the center of the city. Vladimir showered his new muse with diamonds and an imported wardrobe; he hosted opulent gatherings or tributes for her, sparing no expense on the menu or entertainment. Details of the menu from one event reveal that Vladimir's parties featured an array of delicacies, which could include quail, Chinese pheasant, Siberian hazel grouse, red partridge, and French fatted fowl. He also planned the specific pieces he wanted the orchestra to play during the evening. One night featured a program of Mendelssohn, Brahms, and excerpts from Gounod's

Faust

and Bizet's

Carmen

.

18

Those expenditures, however, paled in comparison to the money Vladimir paid out to underwrite Valentina's flourishing career. He purchased operettas for her to star in from a variety of composers. He paid for the other actors as well as supporting personnel, props, and costumes. He even rented out grand theaters such as the

Passazh

(arcade) for her productions.

19

The opulent Passazh was a complex on three levels, complete with shops, a restaurant, and a giant theater hall that seated more

than five hundred people. While his desire to please Valentina motivated him, he also had personal aspirations that amounted to more than simply playing the role of financier. He wanted to gain recognition as a theatrical producerâand in some cases as even more than that. In one instance, Vladimir purchased the rights to a new foreign-language operetta and tried to hire the well-known Mark Yaron, Grigoriy Yaron's father, to translate the production into Russian. Vladimir then made another peculiar request. According to Grigoriy, Vladimir asked that his name be included on the poster advertising the operetta as one of its authors. Mark Yaron, outraged at the bold demand, fired back in a way that infuriated Vladimir. “I only told Smirnov that I was used to seeing his surname not on posters for plays but on vodka bottles,” recalled Grigoriy.

20

Vladimir was deeply wounded, much in the same manner he had been when his first wife refused his hand when it was offered. He was trying to move beyond his past, at least the part that associated him with liquor more than theater. To Vladimir, Yaron's comment, whether intentional or not, belittled his foray into the arts and insinuated that he would never be able to move past his vodka heritage. Vladimir sued Mark Yaron for what he claimed was an unforgivable insult. The outcome of the case is unknown, although its very existence demonstrates just how driven Vladimir was to develop his life in St. Petersburg, free from the taint of alcohol.

The potency of the brand his father built made Vladimir's goal of a new life unusually difficult. Vladimir's ties to his former life in Moscow were as solid as cement. Aleksandra, his second wife, and his young son, Vladimir, still lived there. Vladimir's cold and public snubbing of Aleksandra left her shattered even more than his first wife had been. Worse for Aleksandra was that her husband demanded and received custody of their son. Young Vladimir went to live with his father and Valentina in St. Petersburg during these years, leaving Aleksandra distraught

and desperateâa condition that would later make itself known in a surprising and frightening way.

Vladimir also faced an increasingly hostile populace as the debate over what to do about the alcohol problem raged throughout Russia. The people's ire had been awakened by the events of 1905, and it had not dissipated in the least. As the debate widened and grew more heated, a series of high-profile initiatives in 1909 reflected popular attitudes, which condemned not just the uncontrollable drunkards but also the manufacturers and sellers of spirits. This rhetoric vilified old-time vodka makers like Smirnov, much in the same way as Chekhov's column had two decades earlier.

Mikhail Chelyshev was a merchant who had been elected to the Duma on an anti-vodka, anti-monopoly platform. Referred to informally as “a sobriety apostle,” he crusaded against what he believed to be a chief cause of revolutionary fervor: “The system of national alcoholization.” He fought against all aspects of the alcohol trade believing alcohol to be a core weakness that prevented his nation from achieving greatness. Wisely, he utilized Lev Tolstoy to sharpen his point.

21

Chelyshev paid a visit to the eighty-one-year-old Tolstoy in October 1909. The distinguished writer, though frail, remained a passionate temperance advocate and was a supporter of Chelyshev. The two discussed how best to educate citizens about the harmful nature of liquor. One solution was to put a menacing label on all bottles of state-produced vodka. Chelyshev asked Tolstoy to design the label, which he did, proposing a simple yet powerful script. Alongside a sketch of a skull and crossbones, Tolstoy suggested just one word: “Poison.”

22

He explained, “Wine [vodka] is a poison that is harmful for the soul and for the body. That is why it is a sin to drink wine [vodka] and to treat others with wine [vodka]. Also, it is a bigger sin to produce this poison and to sell it.”

23

It was a novel and brilliant concept. Had Russia adopted it, the country would have been decades ahead of the rest of the

world in warning its people about the health dangers of alcohol. But that was not to be. Though the Duma voted in favor of the warning label, the Imperial Council discussed and then tabled the measure, dooming its passage. Among the chief critics was the tsar's minister of finance, who feared that warning labels would cripple the government's finances.

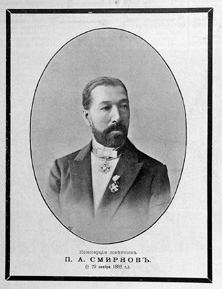

Portrait of Pyotr Arsenievich Smirnov issued in commemoration of his death in 1898. The inscription under the photo reads P. A. Smirnov, Councillor of Commerce, November 29, 1898.

Source:

The Moscow Sheet.

Mariya Nikolayevna Smirnova, Pyotr Smirnov's third wife. She died about four months after her husband.

Source: M. Zolotarev.

The house by the Cast Iron Bridge was the Smirnov residence from the 1860s up until the revolution. The family lived on the upper floor, while a factory, office, and shop operated below.

Source: M. Zolotarev.

View of Pyatnitskaya Street. Smirnov's home is on the left. The belfry pictured is part of St. John the Baptist Church, where Smirnov's funeral service was held in 1898.

Source: M. Zolotarev.