The Kings' Mistresses (3 page)

Read The Kings' Mistresses Online

Authors: Elizabeth Goldsmith

Â

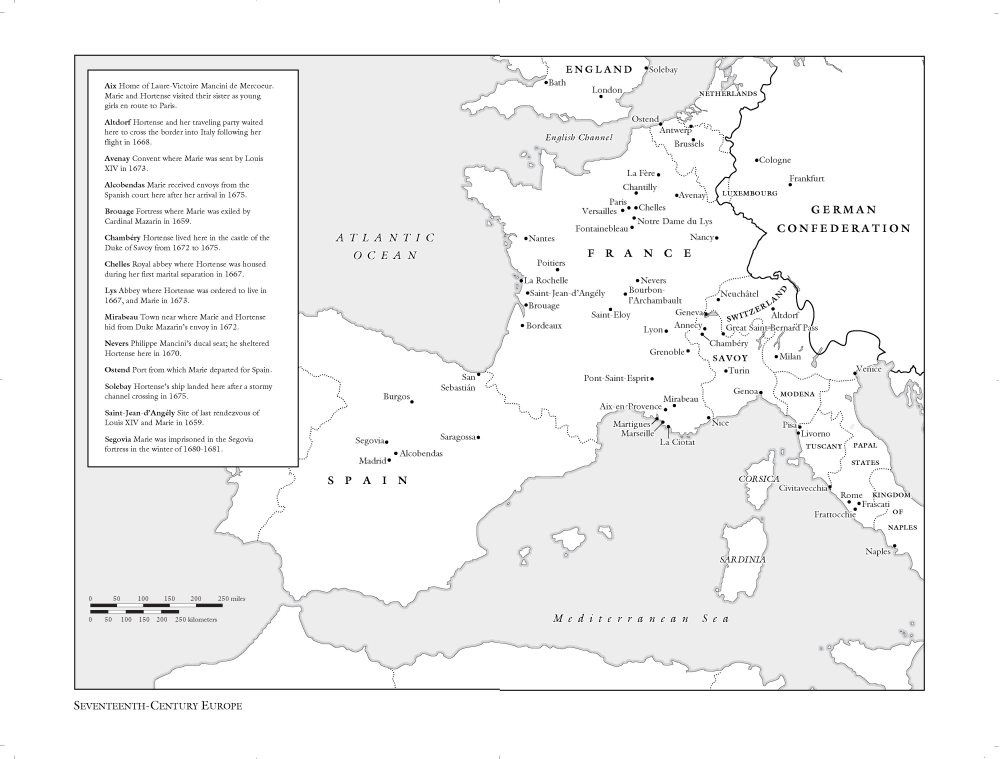

SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE

Â

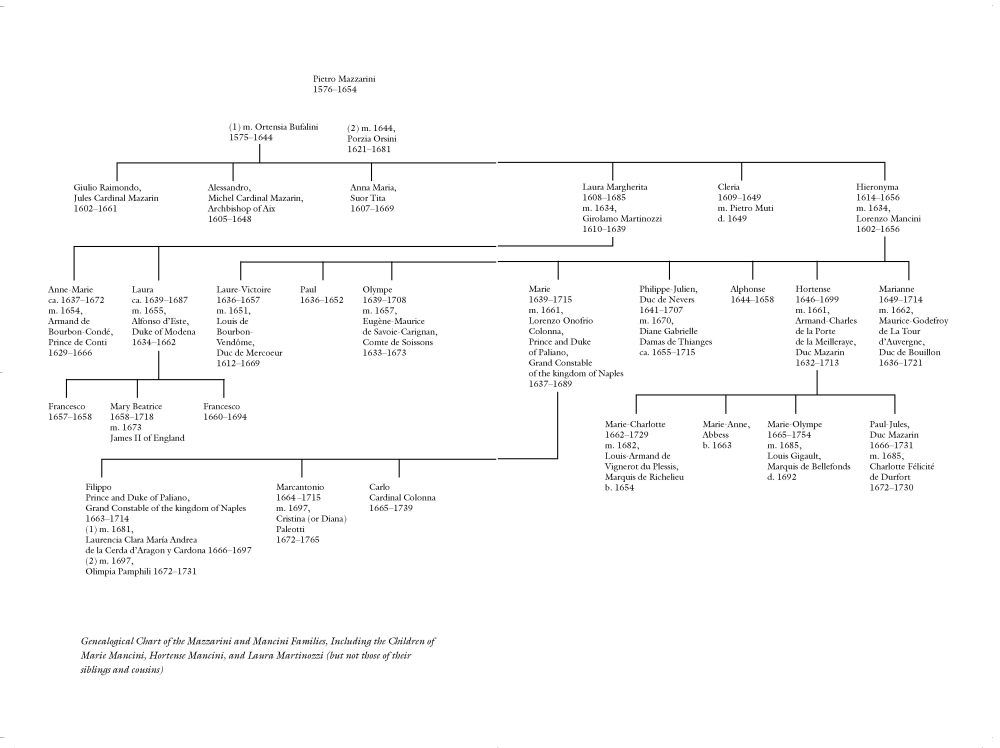

Genealogical Chart of the Mazzarini and Mancini Families, Including the Children of Marie Mancini, Hortense Mancini, and Laura Martinozzi (but not those of their siblings and cousins)

Â

Marie Mancini Colonna with pearls in her hair (oil on canvas) by Jacob Ferdinand Voet

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Â

Portrait of Contessa Ortensia Ianni Stella, bust length, in an ivory chemise, with flowers in her hair (oil on canvas) by Jacob Ferdinand Voet (1639â1700)

© Christie's Images/ The Bridgeman Art Library

1

The

CARDINAL'S NIECES

at the

COURT

of

FRANCE

CARDINAL'S NIECES

at the

COURT

of

FRANCE

The greatest good fortune which can happen to this person, is my not deferring any longer to regulate matters; and if I cannot make her wise, as I believe is impossible, at least that her follies appear not any more in the view of the world, for otherwise she will run a risk of being torn to pieces.

Â

âCardinal Mazarin to Louis XIV, August 28, 1659Â

Mazarin was not opposed to this passion as long as he thought it could only serve his own interests.Â

âMadame de Lafayette,History of Henrietta of England

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

HE MAZARIN FAMILY did not have noble origins. The rapid rise in their fortunes came from the unprecedented success of one man, Giulio Mazzarini (as he was called in Italy), at the French court. Invited there in 1639 to serve as a diplomat, within two years he was a valued adviser to Louis XIII and his minister Richelieu. In 1641 he was made cardinal, and when Richelieu died later that year, Mazzarini was appointed to the king's council of ministers. After the death of Louis XIII, the queen regent named Mazzarini prime minister, a post he retained through long periods of war, civil strife, and revolts against his personal authority,

from 1643 to his death in 1661. Never popular, he was ruthless in his efforts to raise funds for the French wars against the Hapsburgs, the ruling dynasty in Spain, by levying taxes and cutting the salaries of highly placed officials. For himself he loved material wealth, was good at acquiring it, and took pleasure in displaying it. By 1650 he had amassed personal collections of jewels, art, and sculpture that were grander than any in the French royal family. Mazzarini's extraordinary wealth and power and imposing residence near the Louvre palace came to represent all that the French feared in foreign influence. At the height of the Fronde, when French nobles had taken up arms against the powerful prime minister, he took refuge in Germany. Still, by early 1653, he had signed treaties with most of the French princes who had been battling his armies for ten years, and in the spring he returned to Paris. Giulio Mazzarini, now Jules Mazarin, had arrived at the apex of power in France. It remained only for him to embed his family name in the network of royal dynasties that ruled his adopted country. It was only in this way that his personal glory would remain permanently anchored as part of his legacy to France. To that end, he began summoning his family members to Paris. After first importing four of his older nieces and nephews, he wrote to his sisters in Rome asking that they and their remaining children join him at the court of Louis XIV.

HE MAZARIN FAMILY did not have noble origins. The rapid rise in their fortunes came from the unprecedented success of one man, Giulio Mazzarini (as he was called in Italy), at the French court. Invited there in 1639 to serve as a diplomat, within two years he was a valued adviser to Louis XIII and his minister Richelieu. In 1641 he was made cardinal, and when Richelieu died later that year, Mazzarini was appointed to the king's council of ministers. After the death of Louis XIII, the queen regent named Mazzarini prime minister, a post he retained through long periods of war, civil strife, and revolts against his personal authority,

from 1643 to his death in 1661. Never popular, he was ruthless in his efforts to raise funds for the French wars against the Hapsburgs, the ruling dynasty in Spain, by levying taxes and cutting the salaries of highly placed officials. For himself he loved material wealth, was good at acquiring it, and took pleasure in displaying it. By 1650 he had amassed personal collections of jewels, art, and sculpture that were grander than any in the French royal family. Mazzarini's extraordinary wealth and power and imposing residence near the Louvre palace came to represent all that the French feared in foreign influence. At the height of the Fronde, when French nobles had taken up arms against the powerful prime minister, he took refuge in Germany. Still, by early 1653, he had signed treaties with most of the French princes who had been battling his armies for ten years, and in the spring he returned to Paris. Giulio Mazzarini, now Jules Mazarin, had arrived at the apex of power in France. It remained only for him to embed his family name in the network of royal dynasties that ruled his adopted country. It was only in this way that his personal glory would remain permanently anchored as part of his legacy to France. To that end, he began summoning his family members to Paris. After first importing four of his older nieces and nephews, he wrote to his sisters in Rome asking that they and their remaining children join him at the court of Louis XIV.

On a warm spring day in 1653, two young girls stood on the docks of Civitavecchia, Italy. With them were their twelve-year-old brother, two female cousins, their finely dressed mother and aunt, and a small entourage, preparing to board an elegantly outfitted galley headed for the coast of France. The sight must have caused something of a stir in the busy seaport, where onlookers were more accustomed to seeing fishing boats or larger sailing vessels loaded with silks and other luxury goods. This boat was unusual; it had been commissioned in Genoa and detailed with particular attention to the elegant top deck, which was furnished with tented

dining spaces and tapestried furniture. Belowdecks, in the galley, was the more familiar sight of about twenty thin and muscular oarsmen, most of them prisoners or slaves, whose unhappy lot it was to provide the power for the voyage.

dining spaces and tapestried furniture. Belowdecks, in the galley, was the more familiar sight of about twenty thin and muscular oarsmen, most of them prisoners or slaves, whose unhappy lot it was to provide the power for the voyage.

The two girls, Marie and Hortense Mancini, were sisters, one a dark-haired and intelligent-looking adolescent of thirteen and the other a mere child of six, with curly black hair and of more fragile appearance than her sister, but striking in her delicate beauty. Marie and Hortense's father, Lorenzo Mancini, was a Roman baron highly respected for his knowledge of astrology and necromancy. When Marie was born on August 28, 1639, his reading of the planets did not augur well. It was said that this child would bring trouble to the family. Lorenzo Mancini would die in 1656, before he could have any idea about the accuracy of the prophecy.

The Mancini children were curious to see for themselves the pleasures of French society that they had heard about in letters and the accounts of travelers. In Rome the girls had received the customary convent education designed to prepare them for either domesticity or a life in religion. Indeed, their mother had urged Marie to think seriously about staying behind in Rome and committing to a religious life. This was never a likely prospect: although the nuns had taught the girls to read, their favorite books were not those kept in convent libraries. Romance novels, plays, and works on astrology and necromancy all were found in the Mancini household. All of the children, especially Marie, had come to love the epic romances of Ariosto and Tasso. She had heard that in France, women were writing novels and tales inspired by these popular Italians. When their mother announced her intention to leave for Paris, taking with her only young Hortense and brother Philippe, Marie had responded deftly that “there were convents everywhere, and that if it should please heaven to inspire such pious impulses in me, it would be as easy to follow them in Paris as in Rome.”

1

So both sisters,

Marie and Hortense, were with their mother and brother as the family boarded the galley destined for Marseille.

1

So both sisters,

Marie and Hortense, were with their mother and brother as the family boarded the galley destined for Marseille.

Twenty years later, Marie would recall her departure from Italy and the marvelous floating home that Genovese boatbuilders had specially prepared for the little group of voyagers:

So we boarded a galley from Genoa, which that republic had sent to us out of special consideration for Monsieur le Cardinal. I will not stop here to describe that movable house. It would take up too much time to portray all its beauty, its order, its riches, and its magnificence. Suffice it to say that we were treated like queens there and throughout our voyage, and that the tables of sovereigns are not served with more pomp and brilliance than was ours four times a day.

2

2

Cardinal Mazarin had arranged for a voyage that was not speedy; he wanted his Italian family to have time to talk about France, practice the language, and become acculturated to French ways en route to Paris, and so the galley slaves were ordered to row slowly, instructions also intended to ensure a comfortable voyage for the passengers above. It took more than a week for the galley to reach the coast of France. After landing in Marseille, the party spent eight months in southern France hosted by their eldest sister, Laure-Victoire Mancini, who had married the French Duke of Mercoeur.

The seventeen-year-old Laure-Victoire was only too happy to be reunited with her sisters and brother, and she delightedly embraced her task of helping her family understand what to expect at the French court. To the mothers' initial dismay but the children's amusement, Laure-Victoire taught them that it was considered gracious to greet a guest with a kiss. They learned the importance of choosing the right visitors with whom to pass the time in salon society, and they watched in astonishment as the regional consuls arrived

with delicate and expensive gifts: candied fruits, wines, silver candlesticks. By the time the family left for Paris, they had seen ample evidence of the enormous privilege and power their uncle enjoyed. The days of the Fronde rebellions against him were over. His relatives could bask in the security of the cardinal's prestige in the king's close entourage.

with delicate and expensive gifts: candied fruits, wines, silver candlesticks. By the time the family left for Paris, they had seen ample evidence of the enormous privilege and power their uncle enjoyed. The days of the Fronde rebellions against him were over. His relatives could bask in the security of the cardinal's prestige in the king's close entourage.

Still, they were stunned by the luxury of the Mazarin palace when they arrived in Paris in February 1654. The cardinal received them in the lavish surroundings that had raised the anger and jealousy of the French aristocracy just ten years earlier. The manner in which Mazarin had acquired his fortune had been the subject of much speculation during his own lifetime, and even today continues to be a matter of historical controversy. He had used his power without compunction, in the tradition set by his compatriots the Medici family of Florence, focusing on exerting control over his potential enemies by using the ruthless financial weapons being perfected in the early capitalist era: speculation, taxation, forced bankruptcy, expropriation, and money loaned at exorbitantly high rates. In the process he had amassed a fortune that had a modern aspect to it, based heavily on material goods and money, not the landed wealth that traditionally had formed a nobleman's net worth. The interior of Mazarin's palace had been covered with frescoes by the best Italian painters and housed the greatest collection of art known in Europe. It was here that the Mancini children received their first visitors from the court, and it was from the Mazarin palace that the family would take the short carriage ride to the Louvre to pay court to the queen regent and her son, Louis.

The newcomers were objects of much curiosity and rumor. Mazarin had already arranged one marriage whose grandeur had secretly enraged many courtiers, and now more nieces were arriving on the scene. Within weeks of their arrival in Paris, young Anne-Marie Martinozzi's wedding to Prince Armand de Conti had taken

place, in a lavish ceremony that publicly displayed Mazarin's reconciliation with a family that had opposed him bitterly during the Fronde years. The marriage of Anne-Marie to a royal prince was one of the conditions the cardinal had imposed on this former leader of rebellions. It was an unbreakable seal of Conti's defeat.

place, in a lavish ceremony that publicly displayed Mazarin's reconciliation with a family that had opposed him bitterly during the Fronde years. The marriage of Anne-Marie to a royal prince was one of the conditions the cardinal had imposed on this former leader of rebellions. It was an unbreakable seal of Conti's defeat.

Other books

For Today I Am a Boy by Kim Fu

Disturbed Mind (A Grace Ellery Romantic Suspense Series Book 2) by Charlotte Raine

Villain School by Stephanie S. Sanders

Catching Whitney by Amy Hale

The Secret Mandarin by Sara Sheridan

Come See About Me by Martin, C. K. Kelly

Strands of Love by Walters, N. J.

The Golden Enemy by Alexander Key

Lamb by Bonnie Nadzam

The Twelve Crimes of Christmas by Martin H. Greenberg et al (Ed)