The Knight in History (33 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

MILANESE ARMOR, C. 1450:

OVER HIS HAUBERK THE KNIGHT IS CLAD IN PLATE FROM HEAD TO TOE, WITH MITTEN GAUNTLETS AND ELABORATE SHOULDER AND ELBOW REINFORCEMENT.

(GLASGOW MUSEUMS AND ART GALLERIES)

The fifteenth-and sixteenth-century revival of the old chivalric customs, known mainly from the romantic depictions of Froissart and the Arthurian legend, resulted in what one modern historian has termed an “Indian summer” of knighthood, or at least its external forms.

12

The tournament, held on the occasion of a marriage, a diplomatic mission, or accession to a throne, was an adjunct of theatrical productions and partook of their character. The jousting, usually with blunted weapons, was done by the book, its proclamations, challenges, and individual contests conducted in accordance with rules laid down in manuals and adjudged by a Court of Chivalry. The art of heraldry blossomed into maturity. Tunics blazed with coats of arms over gleaming suits of armor whose plates were sometimes intricately incised, canceling the defensive advantage of a smooth surface. The completeness of the plate also cost something in military practicality through the accretion of weight. A suit of armor for the joust made in Augsburg in about 1500 weighed ninety pounds (41 kilograms).

13

Often pageantry took precedence over fighting. An instance of the elaboration the tournament could receive occurred in 1468 in Bruges on the occasion of the marriage of the duke of Burgundy to Princess Margaret of England. Lasting ten days, the tournament was designed around the conceit of a captive giant and the princess of an unknown isle. The champion who freed the giant would win the princess. A dwarf dressed in crimson and white satin led the giant into the lists by a chain, tied him to a gilded tree, and sounded a trumpet, summoning the “Knight of the Golden Tree,” attired in velvet and ermine. Each day of the tournament was marked by different kinds of jousts, ending with a melee on the last day, twenty-five knights to a side. At the final banquet a female dwarf in cloth of gold rode into the banquet hall mounted on a mechanical lion to present a marguerite (daisy) to the new Duchess Margaret, and a sixty-foot mechanical whale was hauled in, its tail and fins working, its mouth emitting music.

14

In England printer and translator William Caxton contributed to the revival with two publications: a translation (c. 1484) of Raymond Lull’s manual for knights, now two centuries old, under the title

The Book of the Ordre of Chyvalry

, and Sir Thomas Malory’s

Morte d’Arthur

(1485). Malory’s treatment of the “matter of Britain” restored Arthur to the central role he had lost in the French romances. The mysticism of the Grail legend, the rigmarole of courtly love, and the nuances of satire found little favor with Malory, who, like Caxton, looked back on the age of chivalry with the blind eye of nostalgia. Both Malory and Caxton fitted their view of chivalry into the more modern sentiment of nationalism, Caxton urging Englishmen to “read Froissart,”

15

in whose pages Edward III and his marauding captains took on the glamour of Lancelot and Arthur. Froissart was translated into English in 1523 by John Bourchier, Lord Berners, who explained that his intention was to make available to the “noble gentlemen of England…the high enterprises, famous acts, and glorious deeds done and achieved by their valiant ancestors.”

16

Lord Berners’s translation was “commanded” by Henry VIII, an enthusiastic practitioner of knightly exercises, whose accession to the throne was celebrated with splendid jousts in which the king himself took part, wearing tilting armor of his own design. Later Henry arranged with German emperor Maximilian, another devotee, to import German armorers to man his “Almain [German] Armouries” at Greenwich. Henry maintained permanent tilting areas at Westminster, Greenwich, and Hampton Court,

17

but the climax of his tourneying occurred when he met Francis I of France in the “Field of Cloth of Gold” near Calais in 1520. Both kings jousted, Francis’s horse in purple satin trappings trimmed with gold and embroidered with raven’s plumes, Henry’s in cloth of gold fringed with damask. French knights wore doublets of cloth of silver and purple velvet, English of cloth of gold and russet velvet. Archery, now displaced by gunpowder small arms, was also a nostalgic feature of the tournament, Henry proving himself “a marvelously good archer.” Wrestling was added extemporaneously to the program. A chronicler reported that after the jousts the two kings “retired to a pavilion…and drank together, and then the king of England took the king of France by the collar and said to him, ‘My brother, I want to wrestle with you,’ and gave him one or two falls. And the king of France, who is strong and a good wrestler, gave him a ‘Breton turn’ and threw him on the ground…. And the king of England wanted to go on wrestling, but it was broken off and they had to go to supper….”

18

In the reign of Queen Elizabeth, elaborate tournaments continued, but the actual jousting became secondary to masques and allegories and displays of horsemanship (manège). Tournaments were now irrelevant to the careers of knights and gentry, whose functions were those of a governing class, a transformation reminiscent of that of the Roman

equites

, and whose military role, though it continued, was no longer the clash of shock combat. The education of the knight as set forth in a plan that Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1537–1583) conceived for an academy in London to train “the youth of nobility and gentlemen” is indicative of the changes. The young gentlemen should study Latin language and literature, philosophy, law, contemporary history, oratory, heraldry, and courtly protocol. They should learn the art of war, but instead of lance and sword they must master mathematics, engineering, ballistics, and military theory.

19

To Caxton and Malory, chivalry was a practical mode of conduct fallen into disuse but susceptible to revival. A hundred years later, in Edmund Spenser’s

Faerie Queene

(published 1590–1596), it had faded to a romantic memory of “those antique times / In which the sword was servant unto right.”

20

Spenser drew his inspiration in part from the Italian poet Ariosto (1474–1533), whose intentions, however, were very different. Ariosto belonged to an Italian tradition developed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries combining the epic material of the

chansons de geste

with elements of the romances. Matteo Boiardo’s

Orlando Innamorato

(

Roland in Love

, 1483) mingled Charlemagne legend and Arthurian romance in a lively combination of heroic deeds, magic, and love. In his satiric

Orlando Furioso (Roland Mad)

, Ariosto pictured knights and ladies living by the old codes of chivalry and courtly love in a sixteenth-century world in which “the cruel art” of artillery had eclipsed the sword, and “martial glory [is] lost.”

21

Where the epic Roland was the model of loyalty to his lord, Ariosto’s Orlando forsakes Charlemagne for the love of a lady, only to be driven mad when she runs off with a Saracen foot soldier.

Ariosto was neither the first poet nor the last to treat chivalry satirically. Both an English verse written by an unknown author around the middle of the fifteenth century,

The Turnament of Totenham

, and the slightly earlier Swiss comic poem, Heinrich Witten-weiler’s

Ring

, describe tournaments in which peasants joust in a burlesque of the courtly spectacle. In the English verse, village youths vie for the hand of Tyb, the reeve’s daughter; in the

Ring

the peasant Bertschi Triefnas celebrates his marriage to his hunchbacked, flatfooted, goitered sweetheart Metzli Ruerenzumph by a joust on the village green. In both poems, the combatants’ mounts are mares, asses, and workhorses; their helmets baskets, bowls, and buckets; their shields winnowing baskets; their weapons rakes, hoes, and flails. While the “ladies” watch, the rustics at first punctiliously follow the rules of the tournament, but break into a wild free-for-all. The feasts that follow are drunken brawls, the whole effect parodying the clichés of courtly romances as well as the practices of tournaments.

22

The chivalric mystique was rebuffed not only by Renaissance humanism but by Protestantism. Elizabethan moralist Roger Ascham identified the Middle Ages with Catholicism and regarded chivalric literature as the creation of “idle monks or wanton canons.” He lamented the day when “God’s Bible was banished [from] the Court, and

Morte Arthure

[Morte d’Arthur] received into the Prince’s chamber.”

23

The most devastating blow to decaying chivalry was struck by a man who was himself a professional soldier. Miguel de Cervantes’s

Don Quixote

(1605) has been called “the first modern novel.” The gaunt old Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance, his brain addled by reading too much chivalric literature, rides through the countryside on his spavined horse, in rusty armor and pasteboard helmet, fighting muleteers, windmills, and flocks of sheep in the name of his “lady,” in reality nothing more than a “good-looking country wench.” After a long succession of disillusioning experiences, he forswears on his deathbed “all profane stories of knight-errantry…those foolish tales that up to now have been my bane,” and sets down as a condition in his will that his niece should marry only a man who “shall be found never to have read a book of knight-errantry in his life.” Cervantes concludes, “My sole aim has been to arouse men’s scorn for the false and absurd stories of knight-errantry, whose prestige has been shaken by this tale of my true Don Quixote, and which will, without any doubt, soon crumble in ruin.

Vale

.”

24

Such is the power of Cervantes’s ironic but compassionate pen, however, that the reader is in danger of concluding that the rest of the world is mad and the noble old man sane.

In the eighteenth century two distinct currents of thought emerged in respect to chivalry. The rationalist philosophers scorned all things medieval as barbarism, superstition, and ignorance. But a body of conservative scholars, the most famous of them J.-B. de la Curne de Sainte-Palaye (1697–1781), studied the art, subjected the history to critical examination, and edited the literature of the Middle Ages. Sainte-Palaye’s

Mémoires sur l’ancienne chevalerie

(1759), with its description of dubbings and tournaments and account of the code of chivalry, exerted a powerful influence on European intellectuals, including Gibbon, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Southey. His critique revived the popularity of Froissart, who had fallen into neglect, and his

Histoire littéraire des troubadours

(1774), widely circulated and translated, won a permanent place on library shelves. Many of the printed editions of medieval chronicles, literary works, and documents used today were prepared by scholars of the eighteenth century.

25

The industrial age in Britain, however, produced the most spectacular revival of interest in the medieval knight, his milieu, military practices, armor, and above all code of behavior.

26

In the early 1800s Sir Walter Scott re-created in

Ivanhoe

and other novels and poems a world of castles, knight-errantry, and chivalric virtues. It was a world of the distant past, whose defects he acknowledged in his essay on chivalry written for the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

in 1818

*

—fanaticism and superstition, the immorality of “courtly love,” the extravagance of knightly enterprises. But “nothing could be more beautiful and praiseworthy than the theory on which it was grounded.” The best elements of the chivalric code had produced the system of manners of the “gentleman.”

27

Scott himself was such a believer in the code that when a publishing firm in which he was partner went broke, he refused to go into bankruptcy, assumed the entire debt, and spent the rest of his life writing to pay it—indeed, the debt was finally paid off by his posthumous royalties.

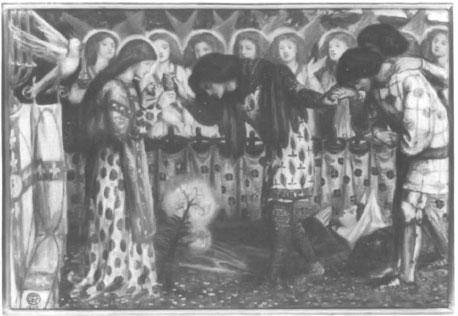

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI,

SIR GALAHAD. (THE TATE GALLERY, LONDON)

Later writers took up the chivalric theme. Malory, who like Froissart had undergone a long period of neglect, was resurrected in a new edition that inspired Tennyson to a series of poems culminating in

The Idylls of the King

. Tennyson’s knights of the Round Table swear