The Last Thing I Saw

Table of Contents

THE LAST THING I SAW

A Donald Strachey Mystery

RICHARD STEVENSON

mlrpress

www.mlrpress.com

Eddie Wenske has gone missing. A popular investigative reporter renowned for both his gay-coming-out memoir and a frightening book on drug cartels, Wenske vanishes while investigating a gay media conglomerate with a controversial owner and dodgy business practices. Albany PI Don Strachey’s perilous search for Wenske takes him to Boston and to New York City, and finally to California and a media world that’s as deadly as it is unglamorous. In The Last Thing I Saw, Strachey fends off hired killers, but can he survive Hey Look Media?

“Entertaining and delectably complex.”

The Washington Post on

Red White Black and Blue

, winner of the Lambda Literary Award for Best Gay Mystery of 2011

“As a page-turner, it couldn’t be better.”

EDGE New England on

Red White Black and Blue

“As always with the Strachey novels, the murder and mayhem take a back seat to the keen social criticism and defiant wit of our detective.”

Maureen Corrigan of NPR, naming

Death Vows

one of the top five mysteries of 2008

“As much travel memoir as mystery, this tenth in a series spanning three decades is supremely satisfying as both.”

Bookmarks on

The 38 Million Dollar Smile

“Lively, skillful…highly recommended.”

The New York Times on

On the Other Hand, Death

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright 2012 by Richard Stevenson

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Published by

MLR Press, LLC

3052 Gaines Waterport Rd.

Albion, NY 14411

Visit ManLoveRomance Press, LLC on the Internet:

www.mlrpress.com

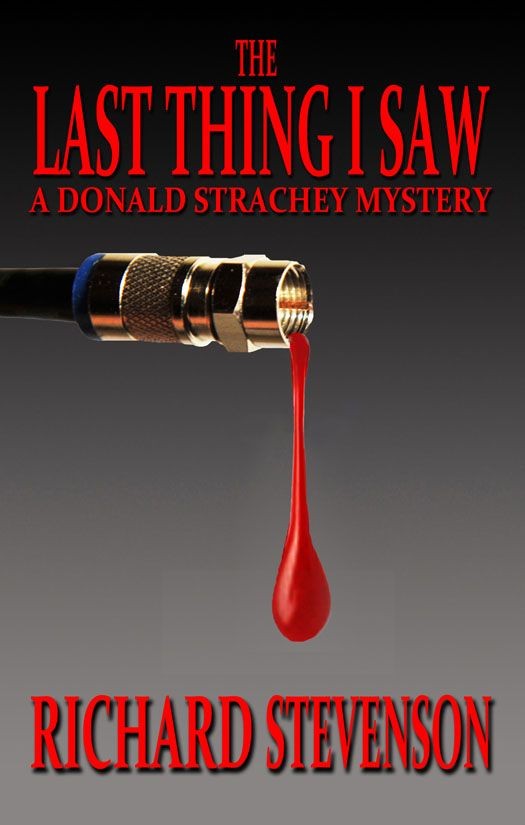

Cover Art by Deana Jamroz

Editing by Kris Jacen

Print format ISBN# 978-1-60820-706-0

ebook format ISBN#978-1-60820-707-2

Issued 2012

This book is licensed to the original purchaser only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of International Copyright Law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines and/or imprisonment. This eBook cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this eBook can be shared or reproduced without the express permission of the publisher.

“Television is a medium because anything well done is rare.”

Fred Allen, in 1950

CHAPTER ONE

“I

told

him not to write that book. If Eddie had listened to me and not written that stupid marijuana book and gotten mixed up with those ridiculous criminals, I’m sure he’d be alive today. We wouldn’t even be having this conversation, Donald. In fact, Eddie should never have left the

Globe

, is what he shouldn’t have done. Kept his newspaper job in Boston and written some nausea-inducing child-molester-priest book, even if a couple of other ones were already out there. But, no, he said, oh no, he just

had

to do that pot book. It was something about, when he was in college Eddie was a pothead himself and he thought it was so totally innocent. And then he found out what all was behind the mellowness, on up the line and at the higher levels—the sociopaths and violent people and what have you. At least I

think

that’s what was going on. How would I really know, he never really explained it to me, I’m only his goddamn agent!”

I said, “What makes you think Eddie is dead, Marva? His mother in Albany just described him as missing. Uncharacteristically out of touch for a couple of months, and that’s why she hired me.”

“Have you read the book?”

“No.”

“Read it. Then you’ll know that they killed him.”

“They?”

“Read the book. Here. It’s what they do to people who cross them.”

Marva Beers heaved herself up out of her office chair, stretched up, and took down a trade paperback book from one of the upper shelves next to her desk. She teetered and then caught herself, a good one-eighty in a pretty Mayan huapili, a heap of fluffy gray hair flopping in synch with her bosoms. She smelled faintly of hyacinth with a distant undertone of chardonnay. Behind her was an open window looking down on Hudson Street, and a friendly warm breeze, unusual for late March in New York, blew in and rattled the papers on the literary agent’s desk.

I recognized most of the authors’ names on the spines of the other titles on the shelves, all books, I assumed, by Beers’s other clients. Most were well known gay-lit figures, like the now missing Edward Wenske, whose 1995 memoir of coming out in the eighth grade in the not very enlightened Albany suburb of East Greenbush had won awards and racked up sales at the tail end of the post-Stonewall gay publishing boom. The book Beers handed me was not of that type. Against a marijuana leaf with blood dripping down it was the title

Weed Wars: the Blood and Gore Behind America’s Nice Habit.

“Well, did you at least read Eddie’s memoir?” Beers asked me. “I thought somebody in your line of work would have done a little more homework before showing up here and taking up my time.”

“I read

Notes from the Bush

when it came out. Nearly everybody in gay Albany and literary straight Albany has read it. It’s wonderful.”

“It’s a classic, and one of the sweetest books by a highly intelligent person I’ve ever read, which is surprising what with people as brainy as Eddie sometimes being not all that sweet. I received the manuscript on a Friday—a friend at the Albany

Times Union

told me I had to look at it—and I read it over the weekend. I cried and I laughed and I cried. On Monday I sent it to six editors and said I was setting up an auction for the following week. I had five decent bids come in, and the editor who never bothered to bid was fired around the time the book came out. I doubt if there’s a connection, but there should have been.

Notes

is still in print, and I’ve got over four K in royalties for Eddie, which I wish I knew what the hell to do with. Estelle, my bookkeeper, keeps ragging me, like

that’s

more important, her accounts being tidy, than Eddie probably shoved through a wood chipper on Cape Cod somewhere and dumped in a swamp.”

“When was he last in touch with you?” I asked.

“Not since the last weekend in January. What’s that? Not quite two months.”

“That’s when his mom last heard from him, too.”

“I got back from Key West, and we were going to have dinner. He never called and he never showed. I called his cell, and nothing. I called Bryan, his ex, up in Boston, and he hadn’t heard anything either, and they’d started talking again recently, trying to patch it up, I think. Eddie was supposed to be in the city doing research for the new book, but Craig Palmer, who he usually stays with, said he hadn’t shown up there either. We were all just perplexed, and then we got scared. We knew he’d had threats after the pot book came out last year. The narcs in Boston used the book to figure out the people running some big New England network, and they warned Eddie they heard he’d better watch his back.”

“You’d think pot dealers would be laid back. But I’ve also heard bad things about the people who are the big operators. It’s only the users who are giggly or serene.”

“It’s a hundred billion dollar industry that’s illegal, so naturally unsavory types are going to move in. Just read the goddamn book, okay? You’ll see what I mean. Care for a Necco wafer?”

“Sure. Thanks. White or green?”

She handed me the pack and I took the one on the end, pink, good enough.

“When I quit smoking in ’93,” Beers said, “I bought a pack of these things to get me through the week, and lo these many years later, here I am. But I’m not diabetic. Yet. In Boston one time, Eddie took me over to the Necco factory in Cambridge, the New England Confectionary Company, where the name comes from. That’s gone now—they moved to some distant suburb somewhere, though at least not to Hanoi.”

“When I gave up my beloved cigarettes,” I said, “it was carrot sticks. But that didn’t last long. Pretty soon it was cheeseburgers, and then I just had to get a grip.”

“You look quite fit, Donald. Gay men don’t let themselves go the way we Sapphics sometimes do. I like to think it’s because we have more important things to think about, but I’m not a hundred percent sure that that’s it.”

“So who notified the police that Eddie was missing?”

“Bryan called the Boston cops after a week of asking around and getting more and more frantic. At first they were yada yada yada, just be patient, he’ll turn up, the way cops are trained to talk. And then Bryan finally got hold of somebody who’d read the book. That guy spoke to the feds, and then they all changed their tune. They agreed that maybe Eddie pissed off the wrong people and his disappearance was no coincidence. Supposedly they sent word out, asking all their people on the street if they knew anything about dealers teaching a rat journalist a lesson, but nothing came back. Likewise with the feds, who leaned on the unindicted co-conspirators who’d helped them nail the tycoons they tracked down using clues from Eddie’s book. After a couple of months, what the men in blue concluded was, it was

not

the drug people who had made Eddie vanish. This conclusion, of course, was based on their failure to establish the obvious and then do something about it. They couldn’t admit to being fuck-ups, so they said, oh, it has to be something else, what can we do?”

I looked at the photo of Wenske on the back cover of

Weed Wars.

He was a bright-faced man of forty or so, with a dimpled chin, a crooked smile, an ample unkempt mane, and attentive hazel eyes. The jacket copy said Wenske was a graduate of both Harvard College and Harvard Law School and had worked as a journalist at

The Concord Monitor

and

The Boston Globe

. He had been part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning team that exposed the Catholic priest pedophile cover-ups in 2002. His book before

Weed Wars

was a joint effort with two other reporters on a kick-back scandal among the leadership in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

I said, “Wenske seems to have made his reputation as an investigative reporter. There must be a lot of people who would have liked to be rid of him.”

“You better believe it. Eddie told me stories. Even before

Weed Wars

there were plenty of people in Boston who loathed him. But they were generally white collar types. Or clerical collar. Somehow I don’t think the archdiocese put out a contract on a reporter. In the fourteenth century they might have, but not these days.”

“It’s interesting,” I said, “that Wenske made a splash with his gay memoir but never wrote again mainly for a gay readership.”

“Prior to the new book, the one he was researching, that’s true. The switch was partly economics. There was the bull market of the eighties and into the nineties, and then all the air went out of gay publishing, if you’ll pardon my mixed metaphor.”

“The image of a deflating bull gets the point across.”

“Anyway, criminality was what was grabbing Eddie, turning him on. His father had been a New York State assistant attorney general who specialized in public corruption, and Eddie was heading in that direction himself until he realized that what he really wanted to do was write.

Notes from the Bush

was something he had to get off his chest—lucky us—and then he was free to go out and devote his life to exposing powerful types who were ripping people off. It’s just as well, because, as I say, gay publishing is all but

pffffttt

. The big houses don’t do much anymore, and with the small houses that have taken up the slack, writers had better not quit their day jobs. It’s a nice hobby and not much more.”