The Lights of Pointe-Noire (16 page)

Read The Lights of Pointe-Noire Online

Authors: Alain Mabanckou

However, the constant changing of titles wasn't over yet, and Governor Victor Augagneur's place in posterity was by no means yet secure in the coastal city. The Marxist-Leninist regime of the âImmortal' Marien Ngouabi, who came to power in 1968, would upset things all over again. Indeed, during his reign, there was much talk of âindependence of spirit' and solidarity with communist brothers the world over, how the proletariat of all countries must unite for the final struggle. Above all, âmental colonisation' must be wiped out, and the order went out for the systematic clean-up of anything which recalled, dimly or vividly, the domination of the white man, and above all of the new enemy, capitalism and its ideology of exploitation of man by his fellow man. The policy must start at the top, so under Marien Ngouabi the country would be called, not the Republic of Congo, but the âPeople's Republic of Congo'. Schools, roads, railway stations with colonial names were all gradually rebaptised with the names of Congolese heroes or promoters of communism. The secondary school where I had recently passed my school certificate, or âbrevet', was called the Trois Glorieuses secondary school in memory of the three days â 13, 14, 15 August 1963 â during which the Congolese trade unionists and their sympathisers ousted Fulbert Youlou, a polygamous priest of the Roman Catholic church, and first president of our country, who tried to impose a one-party state.

By the time I passed into the second year of lycée in 1981, the school had already changed its name and had been known as the Lycée Karl Marx since 1975. President Marien Ngouabi had been assassinated by his own supporters in 1977, but the politicians who succeeded him pursued exactly the same line of âscientific socialism', mixed up with a little tropical capitalism. We looked to the Soviets to teach us mathematics, chemistry, physics and philosophy. Obviously we now swore by Lenin, Engels and Marx; all those other philosophers, like Plato, Kant and Hegel were too idealistic, according to our authorities, and were outlawed, to be mentioned only in contrast to the âtrue' philosophers, those who had introduced and analysed âhistorical materialism' and âdialectics', notably the authors of the

Communist Party Manifesto

, whose portraits hung proudly in every classroom, on the main streets, at intersections, beside the official photo of the man who was president of the republic, head of the government and president of the central committee of the single party, the Congolese Workers' Party, all rolled into one. The systematic linking of our head of state with Karl Marx and Engels led us to feel that all three were thinkers of equal stature, even if we only ever learned speeches by our president, rather than profound philosophical texts. For the average Congolese person, the president was as much of a philosopher as Marx or Engels. So you could study Marxist-Leninist thought in the speeches of the head of state, instead of wasting your energy reading a great tome like

Das Kapital

by Marx, or a short but nonetheless deep book like

Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy

, by Engels. So the pupils mostly quoted the president, who himself had quoted Marx and Engels, and thus we learned what some secretly termed âthe philosophy of poverty'.

One direct consequence of the influence of the Soviet Union on our education was the decline of two languages considered to be the languages of the capitalists, and therefore to be banned: English and Spanish. You have to wonder why we continued to use French, with the implication that this language hadn't come from the capitalist world, and was actually a Congolese language.

The fact remains that Russian became the first foreign language, particularly since the USSR offered the Congolese bursaries by the bucketful, despite the shortage of candidates who, for the most part, secretly dreamed of going to study in France, rather than of joining the ranks of cut-price graduates returning from Moscow, who were then given jobs at the School of the Party, to spread Marxist-Leninist ideology. In an attempt to get the pupils to look to the Soviet Union, some teachers who were members of the Congolese Workers' Party would sneer:

âWhat the hell use is English going to be to you, since you're never going to go to England?'

The supervisor isn't surprised when I ask to meet my old philosophy teacher, who is by far the teacher who left the greatest impression on the âStream A' pupils in my generation at the lycée. Since we didn't know his first name, we called him âMonsieur Nimbounou', or behind his back by his nickname, âNimble'. We'd pass him on the Avenue of Independence, standing at a bus shelter, with his briefcase, on to which he had stuck a picture of Auguste Rodin's

The Thinker

. When asked what it symbolised, he would reply:

âThroughout our lives we should be constantly challenged by the thoughts of the great writers. Rodin's

Thinker

is an example of the man who is constantly engaged in thought, and having him with me imposes a spiritual discipline which even religion cannot offer the faithfulâ¦'

The supervisor tells me that Nimble doesn't teach philosophy any more, that he is a Board Inspector now. And he's over in a different part of the building where a teachers' meeting is being held.

We cross the schoolyard and go over to the meeting room. Outside, the supervisor hesitates, asks me to wait for a moment, and goes in without knocking. Less than two minutes later he comes back out, followed by a man in a suit.

For a moment I don't move, transfixed once more, I think, by the fascination this teacher exerted on us as pupils, when he arrived in class with his briefcase, and suddenly all the chatter ceased. He would enter slowly, place his things on a table and sit down on a chair by the window. He would open a book and begin the lesson, without a hint of a cough in the room. His teaching was seen as an invitation to independent thought, a far cry from the slogans of the Party. Setting aside Karl Marx and Engels, he would randomly invoke Descartes, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Plato, Kant and Nietzsche. Philosophy seemed to us like an extraordinary odyssey, spiced up with entertaining anecdotes, such as the one about Diogenes of Sinope who lived in a tub. Monsieur Nimbounou took a sly pleasure in explaining to us how this particular philosopher was a sworn opponent of conformism, barking like a dog, pissing and masturbating in public. And when he spoke of Epicurus and the cult of pleasure, we all smiled, and he did too, with that sly look of his, which he has to this day. He would stand up, looking very serious, and say:

âNow Epicurus had the right idea, he defined pleasure as the absence of pain. I share his view myself, though it must be said that the perversity of human beings is such that sometimes pleasure, for some people, can only be achieved through pain. Which goes to show that at all times you must seek the antithesis of any given thesis, and from there proceed to a synthesis which reflects your independence of mindâ¦'

Hypnotised by the breadth of his knowledge, we created a discussion group in the lycée. During these sessions, in which we also talked of poetry, we would imitate him by reading whole pages of some âcapitalist' philosophy which was taught nowhere except in our class. We were disappointed to discover that the study of historical materialism did not provide the same delight or enthusiasm as classical philosophy. But Monsieur Nimbounou could not entirely neglect the programme imposed by the Ministry of Education. So he would skim over the thought of Marx and Engels and quickly come back to what he considered true philosophy, that of the school of Antiquity.

We have been chatting for ten minutes or so, not far from the meeting room. Monsieur Nimbounou is talking about my books, some of which he has read:

âMy favourite of all is

Memoirs of a Porcupine.

Perhaps because, without realising it, you posed some philosophical questions in it. Can animals be philosophers? Isn't philosophy exclusively a feature of human thought? That's pretty well what I taught you back thenâ¦'

The supervisor agrees with a nod of the head, while, to change the subject, I tell Nimble that I thought he had retired.

He smiles:

âOur country doesn't yet have enough philosophers for me to be able to retire. And I'm afraid that until my dying day there will be some who go on believing it's possible to live without philosophisingâ¦'

Just as I'm leaving him, I take an envelope from my pocket and hand it to him. He smiles again and pockets it. In the meeting room a voice can be heard saying:

âWhat about us? Don't we get anything?'

Nimble turns round, surprising some of his colleagues, who are watching through the slats in the blinds.

âHe wasn't your pupil, that's the difference,' he says, in their direction.

He folds me in his arms and murmurs:

âI have to go back into the meeting. I'm so glad you came⦠Don't forget: some philosophers only interpreted the world; what we have to do now is transform it. That's possibly the only thing I learned from Engels, for everything else you're better off with the philosophy of Antiquityâ¦'

He returns to the meeting room while we go back the way we came and the supervisor asks me quietly:

âWhat was in the envelope?'

âJust some money, to buy a beer.'

âHe doesn't drinkâ¦'

âWell, he can buy himself a lemonade, at leastâ¦'

At the exit to the lycée the supervisor looks sad:

âYou will come back and visit us again one day, won't you?'

âOf course!'

âBut when? Twenty-eight years from now? We'll all be dead, and maybe the school won't even be called Victor-Augagneur any more! I'll have gone to join our dear departed Dipanda, up aboveâ¦'

I reply, without conviction:

âI'll try not to leave it another twenty-eight yearsâ¦'

Jaws

F

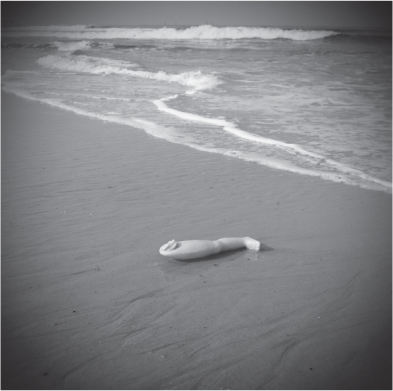

ew Pontenegrins ever dare come as far as this part of the port. Placide Mouembe, my childhood friend, has driven me here, at my request. But he prefers to remain at a distance.

âDon't go any farther!' he yells, increasingly anxious as I gradually advance towards the water.

In his car, all the way here, he kept telling me I must be careful. And he gave me strict orders:

âWe can go the whole length of the port and back, if you want, but please let's not go to that cursed place where there are all those rocks. Strange things happen down there. I don't want anything to happen to usâ¦'

I decided he must be thinking of the times we used to roam down the beach in the hope of finding a wrap left behind by a mermaid, the famous Mami Watta. According to legend, whoever found it would become very rich. The Pontenegrins back then thought that the very wealthy people in our town must have happened upon the wrap of the woman with the fishtail and long golden hair. People from the rougher parts of town would be up at dawn to dash to the bit of the wharf where she was said to live. The most gullible among them would describe the features of this aquatic being with great attention to detail, as though they had actually seen her. She was blonde, or maybe she was black, or maybe a woman with porcelain skin. She was huge, surging out of a great gaping abyss far out to sea, and would come and lie down to rest a few centimetres from the wharf when the ships had gone out. Her piercing eyes lit up the whole of the Côte Sauvage as she stretched out on the sand to comb her hair. What time did you have to get up, if you wanted to see her? Some said around midnight, or even two in the morning. Others said around four. And even so, no one dared come here at these times.

But no, Placide wasn't referring to Mama Watti, but to a different mystery:

âThe ocean keeps many things in its belly⦠the sea is dangerous still, brother, and has no pity. Do you know why the water is salty?'

âI've already heard that oneâ¦'

âYes, the sea tastes salty from the tears of our ancestors, who wept as they made their cursed passage during the slave trade.'

Once we were through the entrance to the port and had parked the car, he began to look worried:

âIt's a bad day to be down by the sea. There's hardly anyone here, the boats look like ghosts watching us, ready to shove us in the water. I'm not going near those rocksâ¦'

I was so insistent, though, that finally he gave in:

âAll right, then, let's go, but we mustn't get too close!'

All around me are the rocks where the waves come to die. As I approach, the sea suddenly falls calm. I can't see what Placide is frightened of, it's such a peaceful place, where any tourist would dream of spending an entire afternoon.

I turn around: Placide is waving at me to come back, but I don't move, I look out across the stretch of sea and imagine what might be lurking in its depths.

A cormorant lands not far away; I turn my head to look at him just as a gigantic wave comes out of nowhere and smashes on to the rocks, wetting my trousers. From a distance, another, even bigger one races in at breakneck speed. I retreat and run back to join my friend, whose face is rigid with terror:

âWhat did I tell you? Did you see that? Wasn't that weird, those two waves? This part of the sea is the kingdom of darkness, it has teeth here and anyone who intrudes on her peace and quiet will be crushed! This is where the bodies of the drowned are washed up. Wherever you happen to die in these waters, it's here that your body will be found! All the sorcerers in this town come and do their stuff here, that's why I didn't want us to get too close to this Zone of Death. The water looks peaceful enough, but if someone comes to stand on the rocks it turns rough, and swallows him with the third wave, which can be as high as a building with five or six storeys, believe me!â¦'

The cormorant I saw earlier passes overhead. Placide follows his flight and concludes, chillingly:

âThose birds work hand in hand with the spirits of the sea. They're accomplices, they tell the monsters of the sea if someone's here! The bird that's just flown over is disappointed, because he didn't get what he wanted: you! Listen, let's go back, we're better off having a drink down by the Rexâ¦'

That evening, after a drink at the Paysanat, Placide dropped me outside the French Institute. I couldn't sleep. I kept thinking of the two waves, and wondering what would have happened at the third wave, if I had stayed on the rocksâ¦

I don't remember ever having bathed on the Côte Sauvage as a teenager. I only ever went down there with the other kids in the hope of getting some sardines, jack mackerels or sole from the Beninese fishermen to take back to my mother, in exchange for help unloading the Ghanaian pirogues. We also went with the secret hope of spying on the half-naked women, particularly white women. The grown-ups said they didn't know how to hide their ânether lands' and made a great exhibition of themselves applying their suncream. Our curiosity bordered on obsession, since we were determined to check whether the blondes also had blond pubic hairs, and if the redheads were red âdown there' as well. Grown-ups idolised body hair to the point where you'd hear them whispering: âI chatted up this girl today, wow, she's beautiful! She's got hair everywhere, long and shiny, straight hair!'

Obviously, because these women depilated their bodies before they went into the sun, you had to get really close to see anything. Startled by our invasion, they would call us all the names under the sun, and go and complain to the coastguard of the Côte Sauvage, who would throw us off the beach.

Many of us, like myself, had never bathed in the sea here, scrupulously following the recommendations of the local sorcerers as to how to keep hold of our physical strength. We often went to ask their advice, and they would prepare gris-gris for us, to make us invincible when we got into fights. With the gris-gris to protect you, if you gave your opponent a thump on the head, he would fall unconscious, or his head would go into such a spin he'd start picking up the garbage that lay round about him. People said that some of these gris-gris, made in the most far-flung villages in the south of the country, like Mayalama, Mpangala or Boko, were so powerful that if you slapped a tree, the unripe fruits would fall and the leaves would turn to dust. Most of the kids were tempted by these fetishes from the age of fourteen. You just had to turn up at the sorcerer's house with one litre of palm wine, and one of palm oil, a packet of Gillette blades, some cola nuts, chillis and charcoal. The guru would get out his arsenal of amulets, murmur a few obscure words, light some candles and ask you to hold out your wrists. He'd grab a Gillette blade and make three little cuts on each of your wrists. Once the blood began to flow he would rub on a black powder, which stung. You were not allowed to cry out or give any sign that the power was entering into you. For the pain he'd get you to chew on some cola nuts and drink a glass of palm wine. You paid him for his work, and he gave you a list of things you mustn't do: don't look under your bed, don't put your left foot down first when you get out of bed, don't approach women, and most of all, don't swim on the Côte Sauvage. How could you check that the power had entered you? The sorcerer would slap you several times. After a moment, you went into a trance, mind and body. Then he'd hand you an empty bottle and ask you to smash it over your own head. If the glass broke without cutting you, it was a total success. Then you had to go and pick a fight with someone in the street, to be quite sure you were as strong as Zembla, Tarzan and Blek the Rock, all rolled into oneâ¦

Indeed, the Côte Sauvage has always been the object of darkest speculation on the part of the Pontenegrins. In their minds, the sea was where the sorcerers from all over town met to draw up a list of all the people who would die in the coming year. Accordingly, any death that occurred here was considered a mystery, the key to which was closely guarded down at the very bottom of the ocean, where all the evil spirits lived, disguised as the fauna of the deep, feeding on human flesh. In short, as soon as a body was seen floating on the ocean surface, these creatures reached out with their giant octopus tentacles to catch them and drag them down to the ocean bed, devouring them at their leisure.

In the ânews in brief' column of our local newspapers back then, they kept a record of drownings which eventually turned out to have been sacrificial deaths, sometimes instigated by the family of the deceased. Many of those who drowned were albinos. Local people believed albinos possessed supernatural powers and that if, for example, you slept with an albino girl, you would recover your virility, or get rich. Such was the prejudice against albinos, the sacrificers tended to overlook the fact that albinism is not a curse, simply a hereditary illness found not only among humans but among certain animals too, such as amphibians and reptiles. From an early age we were indoctrinated with this harsh social reality, and we went along with it, so that if we encountered an albino we already began to imagine them drowned, their corpse, at best, washed up on a beach, if the underwater creatures were already busy devouring their previous victims. Charlatans of all kinds stepped into this breach, decreeing that true attonement could be achieved only by sacrificing those individuals whose skin was sufficiently pale and eyes colourless, red, light blue, orange or purplish-blue for them to be blamed for the entire community's woes. The justification was almost always the same: albinos had not been born like that by chance, they were whites gone wrong who unfortunately had landed here, and in any case, once thrown into the sea they would return to Europe where they would recover the true colour of their skin. The sea was the perfect setting for the drama of this return to the cradle. That was the whole point â white men had arrived at our shores by sea, to capture the Negroes and carry them away, to a place no one ever returned from â except albinos, who came back with this strange coloured skin. So we were doing them a favour, sending them back to Europe.

What with all this, we were not exactly surprised that no albino kids ever came to walk with us along the Côte Sauvage. Their parents, if they really cared about their children, would keep them locked up at home, since even out in the street they were not safe from stone-throwing, not to mention the dogs who joined in too, barking at them as though face to face with a monster.

The Côte Sauvage had also swallowed up another category of individuals, dropped unscrupulously into its waters: the crippled and lame. It was a pretty sordid image when, the day after an act of this kind, the sea held on to the corpse of the deceased, but returned their wheelchair. Someone would recover it and take it to sell in one of the markets downtown, where no one would ever question the provenance of this damaged merchandise. There were so many disabled folk dragging themselves around the town, the seller usually found a buyer within the hour.