The Lonely Sea and the Sky (17 page)

Read The Lonely Sea and the Sky Online

Authors: Sir Francis Chichester

I was so ashamed of this panic that at last I made a great effort, and determined to dismiss it from my mind until I had slept. I fetched wood for the fire, taking several rests on the way. I drank some of the Chianti I had brought from Tripoli, but it tasted nasty. I dragged out the rubber boat, pumped it half full, turned it upside down, flopped on it, and fell asleep at once. When I woke half the water had boiled away. I stood it in a corner, tilted it in the hope that the mud would settle, then half filled another can. It was only fifteen or twenty yards from the fire to the water hole, but I took spells all the way. I dipped in the top of my vacuum flask, and drank the boiled water as it cooled. It tasted like nectar. I finished it all, except for some mud and slime at the bottom. I could not eat anything. Now and then I heard a slight rustle among the wood chips beside me, so made an effort and fetched a torch to see if it was a snake. I could find nothing. I drank nearly half a gallon of water from the next lot when it was cool enough. Every few hours through the night I woke and drank again. In spite of this I was still thirsty in the morning. It was about 6 o'clock when dawn came, and I lay indolently on my back watching the sky, or rather the haze, change colour from dark to light grey.

I ran over all the data of the last flight, thinking over each item of evidence, and going through all the movements one by one, a mental dead reckoning. Had I overshot Camooweal? I imagined it an isolated blob of buildings in the centre of a featureless plain. Had I crossed to the north of the track from Alexandra to Camooweal? It seemed a likely thing to happen in the haze, flying low while I was distracted by the instrument board for a few seconds. I felt too tired to move until a buzz reminded me of the plague of flies. Then I jumped up, fetched the map from the plane, and began reckoning the details of last night's flight. I plotted all my movements carefully, one after the other. There was one discrepancy I could not understand. The water bore after Alexandra was shown on one of the maps, but I seemed to have reached it much sooner than I should have done. I had to let that pass. I made allowance for the drift on each of the courses flown, and in the end I reckoned that I was now 10 miles west of Camooweal.

Then I thought of petrol. The gauge showed empty, but the plane was tail down. I shook the plane by one wing, and I could hear a splash in the tank. I decided to measure it exactly. I fished out a hat and a shirt, and buttoned the shirt over the hat, so that only a small aperture was left open in front. It was rather difficult to see wearing this affair, but it kept most of the flies away; they disliked entering the shaded opening. I walked round the water hole and studied all the tracks visible. There were a number of old motor vehicle tracks coming in from different directions from the east, but they all stopped at the water hole. There were cattle tracks from the south and south-west. The track of a shod horse cheered me up, but it was two or three days old. Suddenly I spotted the fresh tracks of a wagon, and got excited. I followed them gaily, but my enthusiasm was short-lived; after fifty yards I found that I had been following the tracks of my own aeroplane.

I took the tin in which I had boiled water the night before and wiped it clean with my handkerchief. I climbed on the wing and held the tin underneath the petrol cock until the tank had slowly drained into it. Measuring with a foot-rule, I found that I had three gallons left. This was good for thirty-six minutes' flying, say 20 miles out and back allowing for warming up, starting and taking off. The reasonable course of action would have been to wait on the ground where I was; the haze might clear which would make it possible to spot Camooweal 10 or 15 miles away, instead of groping about near the ground with visibility of a few hundred yards. Then I should be able to have a rest, which would result in my thinking more clearly, and perhaps getting some good fresh ideas. But I dreaded the prospect of a search being started for me. I made up my mind to try for Camooweal.

I warmed up for three minutes, and set off on a fifteen minute flight to the east, determined to return to the water hole if nothing had showed up by then. Every second of this flight was exciting. There was a strong wind blowing from the south, and the dust haze was thick. The minutes fled as fast as they had travelled slowly the night before. In eleven minutes I thought I saw a man ahead, but it turned out to be a small horse which bolted. At fourteen and a half minutes, I came to a creek. I had a feeling of relaxation. I must return to the water hole. I decided to cross the creek and turn on the other side. I was just going into the bank for turning, when I caught the dull glint of light on an iron roof: it gave me a jolt. Then I saw another â five, six, seven. I cursed and swore as I tore round the place at full throttle, and finally landed. A truck drove up with the station book-keeper and a load of station hands and blacks. I thought that his Scots accent was the pleasantest sound I had ever heard.

This was Rocklands Homestead (3,400 square miles) 4 miles north of Camooweal, and I had been at Cattle Creek water hole, 15 miles to the west, which probably would not have been visited for six weeks. The water hole where I had lost the track must have been an extra one, short of the one marked on the map. The perfectly formed road, which had puzzled me, was the work of a fire plough, I was told. This was my first serious exercise in mental dead reckoning. In 1943, during the war, one of my jobs at the Empire Central Flying School was to devise methods of teaching fighter pilots how to find a pin-point objective in enemy territory while jinking at zero feet. It had to be done by mental dead reckoning, because the pilot could not take his eyes off the ground ahead. It seemed easy after practice, and by using various tricks; it is the first time of doing anything that is difficult.

I was content with my two flights that day: 15 miles to Rocklands, and 4 miles on to Camooweal. The remaining 1,380 miles to Sydney I flew off in three stages. To my surprise and uneasiness ten planes of the New South Wales Aero Club met me, and escorted me to Mascot Aerodrome, where I could see several thousand people on the airfield, waiting for me. I should like to be able to report that I made a perfect landing in front of such an audience, but the true story is that I was so nervous that I did it as badly as I possibly could â touching down with a bump and finishing with a series of rabbit hops. It was a great surprise for me to find myself in the news. I had had no thought before the flight that any fame, or notoriety perhaps, would attach to making the flight. If I had not delayed at Tripoli I should have taken nineteen days over the flight from London to Darwin, three days more than Hinkler took.

PART 2

CHAPTER 11

THE TASMAN SEA

The fame that I ran into hit me like a shock. I had had no thought of it when I left England; I was trying only to achieve a private target that I had set myself. At first I liked being pointed out as a celebrity, while at the same time dreading it; then I began to think that I really must be a bit of a lad, and my head began to swell. I began to dislike not being pointed out to people. I feel ashamed of this period. I think I regained my balance within a year; I grew a beard and hid behind it. People could say anything they liked to me, and I just stood behind the scenes watching and enjoying it without being affected. I was one of the few pilots who had first made the money needed to finance a flight. As soon as I returned to New Zealand, where the slump was now in full swing, I began looking for ways of replenishing the purse. First I wrote a book about the voyage called

Solo to Sydney.

I realised that the only hope of its having any success was to rush it out, and I dictated most of it. Reading it today makes me squirm; yet there were some fine reviews of it, and Christopher Beaumont wrote of it in the magazine

Airways

, 'One of the extraordinarily few classics of aviation literature, full of the art that conceals art.' My excuse for some of the corny passages was that I was still exhausted:

Solo to Sydney

records also that 'every night, almost without fail for nine weeks, I had the same nightmare between 3 and 4 o'clock. I was in the air flying, when my vision went completely and I waited in fearful darkness for the inevitable crash. Usually I woke to find myself clawing at the window or a wall trying to escape.' In view of what happened later I wonder if this was a sort of 'Experiment with Time' experience, or just a coincidence.

Solo to Sydney.

I realised that the only hope of its having any success was to rush it out, and I dictated most of it. Reading it today makes me squirm; yet there were some fine reviews of it, and Christopher Beaumont wrote of it in the magazine

Airways

, 'One of the extraordinarily few classics of aviation literature, full of the art that conceals art.' My excuse for some of the corny passages was that I was still exhausted:

Solo to Sydney

records also that 'every night, almost without fail for nine weeks, I had the same nightmare between 3 and 4 o'clock. I was in the air flying, when my vision went completely and I waited in fearful darkness for the inevitable crash. Usually I woke to find myself clawing at the window or a wall trying to escape.' In view of what happened later I wonder if this was a sort of 'Experiment with Time' experience, or just a coincidence.

Gradually I made up my mind that there were two things I wanted to do: I wanted to complete a circumnavigation of the world in

Gipsy Moth

, and I wanted to fly across from New Zealand to Australia. No one had flown across the Tasman Sea alone, and I had a great urge to be the first to do it. At that time only one solo ocean flight had been completed, Lindberg's flight across the Atlantic. My problem was: how could I span the Tasman? My Moth was carrying sixty gallons with two extra tanks fitted, and taking off with a load equal to its own weight. The Tasman is two-thirds of the width of the Atlantic, and with 15 per cent extra for a safety margin â little enough â I needed over 100 gallons. I could not fit the tanks needed to carry this extra fuel. And 15 per cent extra range was not really enough, because the Tasman Sea is a dirty stretch for storms, which start suddenly, rolling across from east to west. How could I get across? I could not buy or borrow a plane with the necessary range, because there wasn't one in New Zealand.

Gipsy Moth

, and I wanted to fly across from New Zealand to Australia. No one had flown across the Tasman Sea alone, and I had a great urge to be the first to do it. At that time only one solo ocean flight had been completed, Lindberg's flight across the Atlantic. My problem was: how could I span the Tasman? My Moth was carrying sixty gallons with two extra tanks fitted, and taking off with a load equal to its own weight. The Tasman is two-thirds of the width of the Atlantic, and with 15 per cent extra for a safety margin â little enough â I needed over 100 gallons. I could not fit the tanks needed to carry this extra fuel. And 15 per cent extra range was not really enough, because the Tasman Sea is a dirty stretch for storms, which start suddenly, rolling across from east to west. How could I get across? I could not buy or borrow a plane with the necessary range, because there wasn't one in New Zealand.

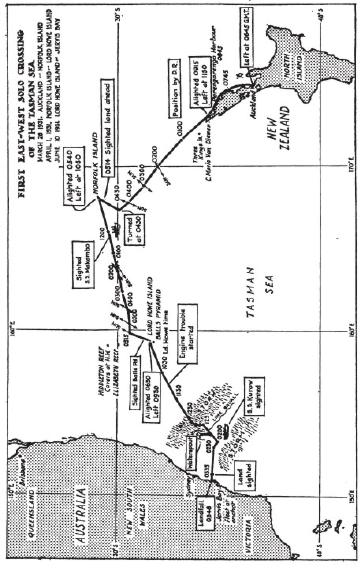

One day I was looking at a globe while shaving and noticed two small islands in the North Tasman Sea. Norfolk Island was 481 miles from the northernmost tip of New Zealand, and Lord Howe Island, 561 miles from Norfolk, was 480 miles from Sydney. I was excited; instead of a blundering flight straight across, could I pick my way from island to island? I could not find anyone who knew if Lord Howe Island was inhabited, but an old encyclopaedia told me that it was of 3,200 acres and 120 inhabitants. No aeroplane had been seen at either island, and according to the charts I managed to get, both appeared too hilly for even a level field. It was difficult to find out anything. A steamer visited the islands once a month from Sydney, taking a week on the outward trip, but I already knew better than to rely on some non-flier's idea of a field suitable for landing in: it might be a tennis court sloping uphill with eighty-foot trees all round!

My next idea was: why not turn the Moth into a seaplane, and alight on the sea? Lord Howe Island had a lagoon, and the idea of blowing in and settling on the lagoon of an untamed island caught my fancy. I decided to learn seaplane flying at once. Here I had a stroke of luck. New Zealand had a sporting Director of Aviation, WingÂCommander Grant Dalton, who had enlisted me in the Territorial Air Force. He said, 'You can do a course of seaplane training instead of landplane training.' I found seaplane flying much more thrilling; there was something wild and free about it, and it called for more flying skill. You must rely on your own judgement for choosing the best water to alight on, estimate wind and tide, and survey the surface for rocks or even small pieces of wood which might pierce the thin floats. A seaplane needs more skill in handling because, with its big floats, it loses flying speed and stalls more easily. If too steep a turn is made, the floats catch the air and tip the plane over, possibly on to its back.

On the water, a seaplane is a fast motor-boat as long as the propeller is turning, but as soon as the motor is cut it becomes a fast yacht, sailing downwind. Broadly speaking, in the air it has all the problems of an ordinary aeroplane, with a fresh set of problems and hazards on the water. It may drift fast on to a pier or a boat astern, and it has not the hardy construction of a yacht. A wing can crumple like paper, and the floats rip open like biscuit tins. At sea (at the time of which I am writing) a seaplane was about as seaworthy as a canoe.

Then there was another set of problems caused by flying the seaÂplane single-handed. Ropes, anchor and drogue all had to be carried, I might have to moor by myself, and usual work on the engine, checking valve clearances, refuelling, etc., might have to be done while the seaplane was dancing like a dinghy in a choppy sea.

Other books

Untamed Hearts (BBW Biker Werewolf Romance) by Catherine Vale

Variations on an Apple by Yoon Ha Lee

Primavera con una esquina rota by Mario Benedetti

Dark Tiger by William G. Tapply

The Dig by Michael Siemsen

Myrren's Gift by Fiona McIntosh

Duty First by Ed Ruggero

The Circus of Adventure by Enid Blyton

Fallen by Callie Hart