The Lonely Sea and the Sky (22 page)

Read The Lonely Sea and the Sky Online

Authors: Sir Francis Chichester

I considered the other bays of the island for trying to take off. The only possible one seemed to be Emily Bay, on the south coast. It had a horrible coral reef, but there was water between reef and shore, and I thought that if I could get a run along the strip of water without the floats being ripped open on the coral, I could get off. The worst feature was a bend in the strip of water at its narrowest place where I should have to change course while taking off, but it seemed my only hope, and I decided to have a shot at it. The question was how to get the seaplane in to Emily Bay. It was a long way to taxi round with the propeller chopping spray all the time. I considered taking it across in a lorry, but there were many objections to this. 'Why not fly her over?' suggested one of the boatmen. Everyone applauded, and I realised that unless the seaplane flew soon people would lose interest in helping me. Hardly anyone had seen the seaplane fly.

I unloaded all my gear and siphoned all the petrol out of the lower tanks, filling ten 4-gallon tins with it. Empty, the seaplane took off at last. She left the crest with one swell, hit the next and sprang off about forty feet in the air. She looked like settling down again, but gathered speed before the floats touched. I climbed to 3,000 feet and made for the lagoon at Emily Bay. I circled the lagoon, studying it, and the longer I looked the less I liked it. Dark blobs of coral sprinkled it from end to end. 'If I look much longer,' I thought, 'I shall get stage fright.' I swooped down and put the seaplane on the surface at high speed and planed fast through where I judged the narrow neck to lie. As I passed the neck I let out the breath I had been holding.

I anchored off the little sand beach in Emily Bay, and Brent and I worked on the seaplane until the evening. I sorted my gear and left behind everything possible, including the rubber boat. I hated doing this, but it weighed 27 lbs with the oars and pump. On my way back to Martin's I suddenly remembered that my nautical almanac, which gave the position of the sun for every hour of the day, ran out on 31 March and that tomorrow was 1 April. There was no other nautical almanac on the island. I had to have one, because I had to rely on sun observations for finding Lord Howe Island. I decided to make a new almanac myself. I needed the sun's declination and right ascension for every hour, so I took the readings for several days beforehand, noted how they changed, and assessed the values for the corresponding times of tomorrow. The cable station checked my watch against Greenwich Time, and I promised to transmit a message every hour of the flight if I could get off.

In the morning, on waking, I walked out into the starlight to study the weather. I knew that I could get off that stretch of water only against a fresh breeze, and it had to be blowing straight up and down. Against a starlit sky I could see the fringe of a tree-top swaying. For the first time since I arrived there was a fresh breeze of 15 to 20mph blowing. I turned my head till it was blowing equally on each cheek â it was south-easterly, almost dead up and down the stretch of water. It was marvellous.

I had to get to the opposite end of the lagoon from where the seaÂplane was anchored in Emily Bay. In such a breeze it would have been impossible to taxi slowly downwind through the channel, so Martin had a dinghy carried overland to Emily Bay, and two boatmen towed the seaplane to the neck in the lagoon, and then let it drift downwind. We reached the end of the reef, and there we moored to an anchor bypassing the rope over a float boom. Brent sat in the rubber boat astern, and held the loose end of the mooring rope. Standing on the float, I swung the propeller and then nipped back into the cockpit. Looking over the cockpit edge I found myself staring into the excited face of a swimmer, half out of water and balanced with his hands on the end of the float. The propeller blades, invisible to him, were cutting past his face, and if he swayed forward an inch he would be killed. I stabbed my finger at him and shrieked. He slipped back into the water with a sheepish expression â I think because of my screaming at him in front of the people, and not because he realised his narrow escape. I felt weak with the shock of having nearly killed him. I pulled myself together, and opened the throttle wide and signed to Brent to let go the rope. The seaplane shot forward and gathered speed quickly. I pressed back in the cockpit, my head as high as possible, darting quick looks from side to side at the reef, to shore, and ahead. I was not aware of the seaplane, or its controls at all. At the narrow neck, about to shut off for having failed, I found to my surprise that I had left the water, and was a few feet above it. I had not enough height to turn properly to avoid a hillock in front, and slithered round in a horrible flat skidding turn. I flew back to the lagoon in a wide sweep. I deeply regretted my rubber dinghy. I could have carried it easily! It seemed terrible to face the distance ahead without it, in this battered, strained plane. But no! I had escaped with the seaplane in one piece, and nothing would induce me to return. I dived, and flew along the lagoon, saluting the crowd. Then I headed west.

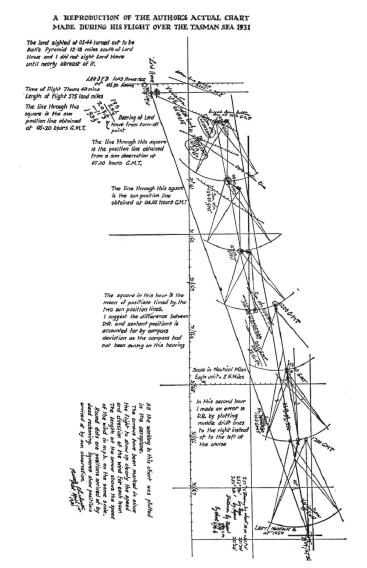

The sun was behind my right shoulder and during the flight I could expect it to move round over the right wing, to ahead. To fit in with this I changed course ten degrees to the right, which should take me 100 miles to the right of Lord Howe Island. This would increase the flight to 600 miles, but it was the only scheme that would find me the island. Using the slide rule and my home-made nautical almanac I calculated what the bearing and distance of the sun-point would be from the island about an hour before I was due to arrive, and then selected the turn-off point along my present line of flight which would have the same bearing and distance from the sun-point as the island at that time. This imaginary turn-off point was my first objective.

I looked back for a last sight of Norfolk Island but was surprised to find it already hidden in a purple haze, although only 15 miles away. I used the same navigation system as on the flight to Norfolk Island, taking three drift readings every half hour, and plotting them. Forty minutes out I slipped the wireless key under a band round my leg to send a message to the cable station. I found the battery current meter needle dancing about madly before I switched on; I assumed that vibration had short-circuited it somewhere, and that the set was useless. But I had no means of checking whether it was working or not, and as I had promised to transmit, I did so.

At the end of the first hour I found that the wind had backed to east by north, and given me a lift of 20 miles. It looked as if I was going to have an easy flight, and I had to fight against drowsiness. I made the calculations necessary to check the compass error as soon as the sun was abeam. This was important, because I had not had an opportunity of checking the compass on this heading, and an error of ten degrees would put the seaplane 100 miles off its course in a 600-mile flight. The method I used for checking the compass was this: I calculated when the sun would be nearly abeam, and worked out how far I would be from an imaginary sun-point if I was on my right track; then, when the time came, I would take a sextant shot at the sun to find out my actual distance from that point. The difference between the two distances would tell me how far I was off the right track.

It was difficult to work; the seaplane was hard to control, and could not be trimmed to fly level. If I took my hands off the controls for a second, it would go into a steep dive, or climb immediately. Besides the nuisance of having to nag continuously at the controls, this meant there was something wrong with the rigging â perhaps a float had been knocked out of trim. The speed indicator on the strut outboard showed that the speed had dropped to 72mph. That suggested that perhaps the propeller might be damaged â that, at least, would explain the terrific vibration. A few months ago I would not have flown the plane in this condition over the safest route in the world, but now I just had to go on.

Glancing to the south I noticed a small black cloud on the horizon and as I watched, it changed shape. It was no cloud, but smoke, and I decided that it must be the steamer

Makambo

on her monthly visit to Norfolk Island. I rocked the seaplane's wings in salute, as excited as if I had seen a ship after being in the water for three days. I seized the wireless key, and tapped out an exuberant message that I could see her; as I finished, she belched out a big smoke, which warmed my heart as a signal that they had heard me on board, or seen the plane. I could not see the ship, for she was below the horizon from me. When plotting my drift observations it occurred to me that the slow old

Makambo

would be steaming a direct course from Lord Howe Island to Norfolk Island. I could see from the chart that she must have been 30 miles away when I joyfully waggled my wings in salute â I might as well have been at the North Pole for all the chance they had of seeing me. It was curious how plain the smoke was, whereas the island had been out of sight at half the distance.

Makambo

on her monthly visit to Norfolk Island. I rocked the seaplane's wings in salute, as excited as if I had seen a ship after being in the water for three days. I seized the wireless key, and tapped out an exuberant message that I could see her; as I finished, she belched out a big smoke, which warmed my heart as a signal that they had heard me on board, or seen the plane. I could not see the ship, for she was below the horizon from me. When plotting my drift observations it occurred to me that the slow old

Makambo

would be steaming a direct course from Lord Howe Island to Norfolk Island. I could see from the chart that she must have been 30 miles away when I joyfully waggled my wings in salute â I might as well have been at the North Pole for all the chance they had of seeing me. It was curious how plain the smoke was, whereas the island had been out of sight at half the distance.

Holding my log-book in my left hand with the little finger crooked round the control-stick, and my other elbow touching the side of the fuselage, I found it impossible to write. This drove home to me that the vibration was not only severe, but dangerous. The whole fuselage was shaking, with a quick short period, and the rigging wires, which should be taut, were vibrating heavily. Why? It was not the motor, because the exhausts were firing with a steady, even bark. I decided that it must be the propeller. I thanked heaven for a following wind and perfect weather; if the seaplane struck bumpy air in this condition God help us.

When I came to plotting three drift lines at the end of the hour I found that I had made some blunder. They should all three meet in a point, or nearly so, but they didn't. It was simply that I had plotted one of them to starboard instead of to port, yet, though I tried to detect this silly mistake time after time, I could not spot it. As I knew that there was a mistake, it showed how stupid I was, either because of the blast of wind on top of my head, the roar of the motor, the salt air, or my weariness, or perhaps anxiety about the seaplane's breaking up.

Glancing down, I had a shock. The compass had worked loose, and had turned until the seaplane was headed north-west. The vibration had rattled out the holding screws. I twisted it back into place, and rammed wads of paper down the side to keep it there. It was now subject to the full force of the vibration, and the needle shivered violently on its pivot. I checked that I had my pocket compass in my belt. Presently I recovered a bit from my worries, and felt hungry. I pulled a tin of pineapple through the hole cut in the seat of the front cockpit, and my mouth watered as I cut open the tin. The juice was like nectar. I cut the slices across with my sheath knife, and ate the chunks with a pair of dividers.

I watched the tin drop in a smooth backward curve turning and twinkling, and I plotted the third hour's flight to find that I had now flown 264 miles. When I needed to know the height to reduce the sextant reading accurately, I found that the needle of the dashboard altimeter was moving round the dial in endless jerks like a full-sized second hand on a clock. The vibration must have broken it. I felt despair â the wireless transmitter, the dashboard airspeed indicator, the compass seating, and now both altimeters broken. How long could the aircraft stand the strain?

As for that pig of an altimeter, it had always tried to fix me. This rage cheered me up a bit. To hell with it! I could judge the height above the water myself; I was getting pretty good at it now. I got three good sights.

During the fourth hour the wind backed about eighty degrees and was now almost a beam wind. At the end of the hour I was 337 miles on my way. I was nearly five hours out, and should reach the turn-off point six hours out. I had to get another sun observation at the end of this hour.

At five hours and ten minutes out I got three good shots of the sun. In computing this result it happened that I was using the bottom of the scale on one of the slide-rule cylinders, and I had to read it sideways, because there was not enough room to hold it in front of me in the cockpit. The result showed that I was 26 miles short of my dead reckoning position. The spectres of every mistake I had ever made rushed through my brain. Now I remembered that the strut speed indicator was over-reading by 5 miles an hour, which accounted for 25 miles in five hours. It had been stupid of me to forget it. So I had done only 391 miles, instead of 417. According to the sextant, I was 100 miles short of the turn-off point.

Looking ahead I could see dark grey rain-clouds squatting on the horizon â bad weather. That seemed more than I could bear. I felt empty of any courage. I tapped out a wireless message; although the transmitter might be useless, the routine act gave me support like an old friend. Before the end of the message I flew into stinging cold rain. There were still some gaps through which the sun shone, and I hurried through my drift observations and the plotting for the hour's flight. I glanced at the petrol gauge â 3½ hours left.

Other books

Shattered by Donna Ball

Free Fall by MJ Eason

Dust and Obey by Christy Barritt

Be Were (Southern Shifters) by Gayle, Eliza

Between Two Fires by Mark Noce

Paradise Red by K. M. Grant

Out of Orange by Cleary Wolters

White Collared Part Two: Greed by Shelly Bell

04 Four to Score by Janet Evanovich

Inside Steve's Brain by Leander Kahney