The Long Tail (24 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

The same Long Tail forces and technologies that are leading to an explosion of variety and abundant choice in the content we consume are also tending to lead us into tribal eddies. When mass culture breaks apart, it doesn’t re-form into a different mass. Instead, it turns into millions of microcultures, which coexist and interact in a baffling array of ways.

As a result, we can now treat culture not as one big blanket, but as the superposition of many interwoven threads, each of which is indi

vidually addressable and connects different groups of people simultaneously.

In short, we’re seeing a shift from mass culture to

massively parallel culture.

Whether we think of it this way or not, each of us belongs to many different tribes simultaneously, often overlapping (geek culture and LEGO), often not (tennis and punk-funk). We share some interests with our colleagues and some with our families, but not all of our interests. Increasingly, we have other people to share them with, people we have never met or even think of as individuals (e.g., blog authors or playlist creators).

Every one of us—no matter how mainstream we might think we are—actually goes super-niche in some part of our lives. For instance, I’m pretty mainstream in my movies, less mainstream in my music, and incredibly niche in my reading, which seems to consist mostly of network economics these days (blame this book). Moreover, where we do go niche, we often follow it much farther than we might otherwise go, letting our enthusiasm take us deep into wine culture or vintage jewelry—because, thanks to abundant choice, we now can.

Virginia Postrel observed that the variety boom is nothing more than a reflection of the diversity inherent in any population distribution:

Every aspect of human identity, from size, shape, and color to sexual proclivities and intellectual gifts, comes in a wide range. Most of us cluster somewhere in the middle of most statistical distributions. But there are lots of bell curves, and pretty much everyone is on a tail of at least one of them. We may collect strange memorabilia or read esoteric books, hold unusual religious beliefs or wear odd-sized shoes, suffer rare diseases or enjoy obscure movies.

This has always been true, but it’s only now something we can act on. The resulting rise of niche culture will reshape the social landscape. People are re-forming into thousands of cultural

tribes of interest,

connected less by geographic proximity and workplace chatter than by shared interests. In other words, we’re leaving the watercooler era, when most of us listened, watched, and read from the same, rela

tively small pool of mostly hit content. And we’re entering the microculture era, when we’re all into different things.

In 1958, Raymond Williams, the Marxist sociologist, wrote in

Culture and Society:

“There are no masses; there are only ways of seeing people as masses.” He was more right than he knew.

IF THE NEWS FITS…

What will this niche culture look like? We can observe the changing media for clues. News was the first industry to really feel the impact of the Internet, and we’ve now had an entire generation grow up with the expectation of being able to have on-demand news on any subject at any time for free. This may be good for news junkies, but it’s been hell on the news business. The decline of newspapers, which are down more than a third in circulation from their mid-eighties peak, is the most concrete evidence of the disruptive effect the Long Tail can have on entrenched industries.

Once, the power of newspapers came from their command over their tools of production. As the saying went, “Never pick a fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel.” But starting in the early 1990s, news started coming on screens, not just smudgy pages. And suddenly anyone with a laptop and an Internet connection had the power of the press.

Initially, the first to take advantage of this were newspapers and other traditional media companies themselves. But as more and more people built first home pages and then blogs, it became less and less clear what the distinction was between professional journalism and amateur reportage. In their own area of interest, the bloggers often know as much as if not more than the journalists, they can write as well, and they are much faster. Sometimes, because they are participants, not just observers, they even have better access to information than the journalists.

Richard Posner, the eminent judge and legal scholar, thinks this is a once-in-a-lifetime game-changer. Writing in a

New York Times

book

review (perhaps for irony’s sake), he observed that with virtually no costs, a blogger can target a segment of the reading public much narrower than a newspaper or a television news channel could possibly aim for. In effect, blogs pick off the mainstream media’s customers one by one by being niche where their old-media precursors are mass:

Bloggers can specialize in particular topics to an extent that few journalists employed by media companies can, since the more that journalists specialized, the more of them the company would have to hire in order to be able to cover all bases. A newspaper will not hire a journalist for his knowledge of old typewriters, but plenty of people in the blogosphere have that esoteric knowledge, and it was they who brought down Dan Rather.

What really sticks in the craw of conventional journalists is that although individual blogs have no warrant of accuracy, the blogosphere as a whole has a better error-correction machinery than the conventional media do. The rapidity with which vast masses of information are pooled and sifted leaves the conventional media in the dust. Not only are there millions of blogs, and thousands of bloggers who specialize, but, what is more, readers post comments that augment the blogs, and the information in those comments, as in the blogs themselves, zips around blogland at the speed of electronic transmission.

The blogosphere has more checks and balances than the conventional media; only they are different. The model is Friedrich Hayek’s classic analysis of how the economic market pools enormous quantities of information efficiently despite its decentralized character, its lack of a master coordinator or regulator, and the very limited knowledge possessed by each of its participants. In effect, the blogosphere is a collective enterprise—not 12 million separate enterprises, but one enterprise with 12 million reporters, feature writers and editorialists, yet with almost no costs. It’s as if The Associated Press or Reuters had millions of reporters, many of them experts, all working with no salary for free newspapers that carried no advertising.

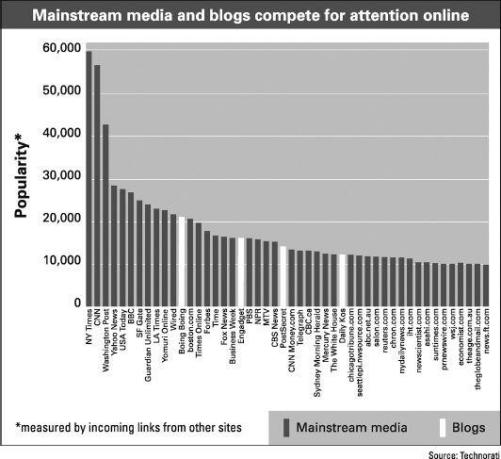

To see this at work, consider this Technorati chart of popularity (measured by incoming links) of Web sites, including both blogs and mainstream media, or “MSM” in blog parlance:

Consider just one of those white lines, Daily Kos (it’s the fourth in). This is a liberal politics site run essentially solo by Markos Moulitsas Zúniga, an activist in Berkeley. It gets more incoming links than the

Chicago Tribune

and nearly a million page views a day. Or go a bit farther down the curve (to rank 65, which is slightly off the page here) to find Instapundit. This is the personal blog of Glenn Reynolds, a forty-seven-year-old University of Tennessee law professor who posts on various topics of interest, from libertarian politics to nanotechnology, during his breaks at work. Because he is smart, opinionated, and fast, he is popular. And because he is popular, he has huge influence. A link from him tends to generate an “Instalanche” of traffic to the favored site, often exceeding that from all but the largest mainstream media sites. He gets more incoming links than

Sports Illustrated

.

Each of these two bloggers has a higher “link authority” than most

of America’s newspapers. This is, of course, an unfair comparison, since the newspapers still do most of their business via their print editions. But if you’re in the newspaper business, the chart above raises some troubling questions about the future of the news business in a Long Tail world.

In

Letters to a Young Contrarian,

Christopher Hitchens writes that he wakes up every morning and checks his vital signs by grabbing the front page of the

New York Times

: “‘All the News That’s Fit to Print,’ it says. It’s been saying that for decades, day in and day out. I imagine that most readers of the canonical sheet have long ceased to notice the bannered and flaunted symbol of its mental furniture. I myself check every day to make sure that it still irritates me. If I can still exclaim, under my breath,

why

do they insult me and

what

do they take me for and what

the hell

is it supposed to mean unless it’s as obviously complacent and conceited and censorious as it seems to be, then at least I know that I still have a pulse.”

The

Times

slogan dates to the late nineteenth century. In 1897 Adolph Ochs, the paper’s new owner, coined the phrase as a jab at competing papers in New York City that were at the time known for yellow journalism. Its original meaning now lost, today the tagline just sounds arrogant and superior.

Was there ever a time when that slogan was true? Probably not, and it certainly isn’t today. As Jerry Seinfeld quips, “It’s amazing that the amount of news that happens in the world every day always just exactly fits the newspaper.”

The reality, slogan aside, is that the

New York Times

now competes not only with other New York City newspapers and newspapers elsewhere, but also with the collective wisdom and information of everyone online. Authority is in the eye of the beholder; it is not innate to the institution itself. It is a credit to the

Times

journalists and editors that they do so well, continuing to break news and set the agenda, despite this. But news and information is clearly no longer the exclusive domain of professionals.

With an estimated 15 million bloggers out there, the odds that a few will have something important and insightful to say are good and

getting better. And as our filters improve, the odds that we’ll see them are getting better, too. From a mainstream media perspective, this is simply more competition, whatever the source. And some audiences will prefer it. Like it or not, fragmentation is inevitable.

A MILLION LITTLE PIECES

Is a fragmented culture a better or worse culture? Many believe that mass culture serves as a sort of social glue, keeping society together. But if we’re now all off doing our own thing, is there still a common culture? Are our interests still aligned with those of our neighbors?

In his book

Republic.com

, University of Chicago law professor Cass Sunstein argues that the risks are real—online culture is indeed encouraging group polarization: “As the customization of our communications universe increases, society is in danger of fragmenting, shared communities in danger of dissolving.” He evokes the famous

Daily Me,

the ultimate personalized newspaper hypothesized by Nicholas Negroponte of MIT’s Media Lab. To Sunstein, a world where we are all reading our own

Daily Me

is one where “you need not come across topics and views that you have not sought out. Without any difficulty, you are able to see exactly what you want to see, no more and no less.”

Christine Rosen, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, shares Sunstein’s concerns. In an essay in

The New Atlantis,

she writes:

If these technologies facilitate polarization in politics, what influence are they exerting over art, literature, and music? In our haste to find the quickest, most convenient, and most easily individualized way of getting what we want, are we creating eclectic personal theaters or sophisticated echo chambers? Are we promoting a creative individualism or a narrow individualism? An expansion of choices or a deadening of taste?

The effect of these technologies, Rosen argues, is the rise of “ego-casting,” the thoroughly individual and extremely narrow pursuit of

one’s personal taste. TiVos, iPods, and narrowcast content of all sorts allow us to construct our own cultural narrative. And that, she says, is a bad thing:

By giving us the illusion of perfect control, these technologies risk making us incapable of ever being surprised. They encourage not the cultivation of taste, but the numbing repetition of fetish. In thrall to our own little technologically constructed worlds, we are, ironically, finding it increasingly difficult to appreciate genuine individuality.

Is Rosen right? I suspect not; in fact, it appears to me to be just the opposite. A world of niches is indeed a world of abundant choice, but powerful guides in the form of recommendations and other filters have emerged to encourage more exploration, not less. We load our iPods with music we get from our friends, and our TiVos ceaselessly suggest new shows we might like based on the watching patterns of others. The evidence from Netflix suggests that when given the ability to pick any movie from a selection of tens of thousands, customers don’t just dive into the World War II documentary niche and never come out. Instead, they become wildly catholic in their taste, rediscovering the classics one month and going on a sci-fi bender the next.