The Long Tail (27 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

The usual defense would be to try to get bigger, adding more and more functionality to Salesforce.com’s offerings to match the features of the big competitors. And that is indeed what Benioff did, initially. But then it occurred to him that he could grow the other way, too. His method of offering software online could also allow hundreds of smaller developers, many of them in low-cost places such as India, to reach those same customers. Typically, companies are loath to work with small developers for fear the software will be buggy and poorly supported and will fail to evolve. By shielding his subscribers from the complexities of installing and maintaining software and instead providing it remotely through a Web browser, Benioff also created a platform through which others could do the same.

What he was doing was applying the Long Tail theory to the software business. And it fit remarkably well. As in other industries, there is a head and tail of software, with Microsoft on one end and millions of individual programmers, many of them in India and China, on the other. In between is the work of a huge number of small groups of developers, most of whom have few good ways to reach customers around the world. But it’s still a very top-heavy distribution: Microsoft’s quasi-monopoly is the ultimate hit-dominated market.

But just as in media and entertainment, three forces are working to change the economics of the software industry. The costs of writing software, which fell dramatically with the spread of powerful PCs, are now falling even faster as the Internet introduces millions of cheap and talented programmers in India and China to the rest of the world. The cost of delivering that software is also falling, as the CD-ROM gives way to the download. And the cost of finding the best software for your specific needs has never been lower, thanks to the hugely connected groups of users online who collectively provide better recommendations (and support) than most high-priced consultants. The ability to offer software through a Web browser, running remotely

without any risk to your own computers, has further lowered all these costs—both real and psychic.

There has always been a market for niche software, starting with shareware traded online and try-before-you-buy demoware. But it wasn’t a huge market, mostly because of the usual problems of risk, complexity, and standards that come with software that has to run on a PC and work with its operating system. The hosted software model offers an opportunity to break through that, by letting professionals deal with most of the complexity and using the Web browser as a universal user interface and shield from the operating system.

In late 2005, Salesforce was the first to launch a Long Tail software marketplace on its platform. Third-party developers could write a targeted niche application (focused on performance reviews or recruiting, for example) and it would run on Salesforce’s servers, integrating with Salesforce’s other software. The hope was that hundreds or even thousands of small developers would meet all the specialized needs of Salesforce’s customers, allowing Salesforce to concentrate on the more common needs. In other words, the tail would reinforce the head. By early 2006, there were more than two hundred applications selling on the marketplace, and Benioff confirms that the shape of the sales curves is just as predicted. “Even I was stunned,” he says. “It’s a perfect Long Tail. Textbook!”

SAP soon followed with its own online platform strategy, as did several smaller companies with similar models. All the usual Long Tail conventions applied. Such companies aggregate niche software on their respective platforms and provide filter mechanisms (ranging from best-seller lists within categories to user reviews). This helps people move with confidence down the curve into niche applications that may suit their needs better than the monolithic one-size-fits-all software that has dominated the market to date. This model neatly connects head to tail.

It’s too early to say how well these new software markets will work, but they are yet another example of how lowering the costs of reaching niches can change the game. As Joe Kraus, CEO of JotSpot (another software company attempting to apply this strategy), puts it, “Up until

now, the focus has been on dozens of markets of millions, instead of millions of markets of dozens.” He, like a growing number of others, is now betting on the rise of the latter.

GOOGLE

The traditional advertising market is a classic, hit-centric industry where high costs enforce a focus on the biggest sellers and buyers. The way it works is that an advertiser, say General Motors, has a marketing budget. GM commissions an advertising firm to create some ads and then a media buyer to place those ads in television, radio, and print and online.

Meanwhile on the other side, those ad-driven media have their own ad sales forces. They pitch the advertisers and their media buyers on the virtues of their advertising vehicles. If all goes well, millions of dollars change hands. All of it is labor-intensive and made even more costly by the expensive schmoozing that’s required in businesses where a lack of trusted performance metrics makes salesmanship and personal relationships key to winning business.

Most ads, whether they run in the Yellow Pages or during the Super Bowl, are actively sold phone call by phone call, visit by visit. Very few just appear because somebody decided to advertise. These days salespeople don’t just twist arms, they also serve as advertising consultants, informing advertisers about the most effective ways to use a given medium or brainstorming creative new approaches to getting the advertisers’ message out. That works well enough, but because it’s expensive, it imposes a subtle cost: a focus on just the largest and most lucrative of potential advertisers. In other words, the system is biased toward the head of the advertising curve.

As with every other market we’ve looked at, that head is just a tiny fraction of the potential market. But because it’s so expensive to sell advertising the traditional way, the smaller potential advertisers have been left to their own devices, mostly picking up a phone and placing a classified ad or sending some homemade display copy to the local newspaper.

That’s pretty much how advertising has worked for most of the past century. But in 2001, a two-year-old Google, the fastest-growing search engine on the planet, started looking for a proper business model. And just as it had done search differently from its predecessors, it decided to do advertising differently, too. Borrowing a model pioneered a few years earlier by Bill Gross, the entrepreneur who started Overture, Google built what would become the most effective Long Tail advertising machine the world has ever seen.

What Google realized is that if it could take most of the cost out of both selling and buying advertising, it could dramatically increase the pool of potential ad buyers and sellers. Software could do almost all the work, thereby lowering the economic barrier to entry and reaching a much larger market.

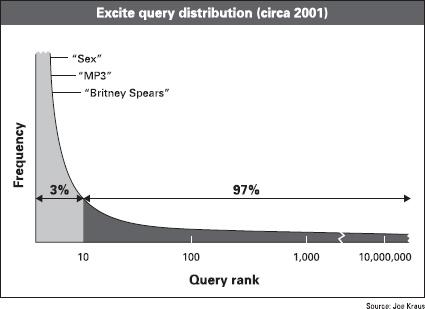

Google’s advertising model has three important Long Tail characteristics. First, it is based on search keywords, rather than banner images, and as we’ve already seen, there is a virtually infinite Long Tail of words and word combinations. Search terms work the same way—here’s a chart of search terms (circa 2001) provided by Joe Kraus, the cofounder of the Excite search engine:

The top ten words account for just 3 percent of all searches. The rest are spread between tens of millions of other search terms. What Google realized is that each one of those unique search terms is an equally unique advertising opportunity: tens of millions of expressions of interest and intent, each of which could be converted into a highly targeted advertising opportunity if the ad placement were determined by exactly the same PageRank algorithms as those that return Google’s search results.

But how to sell tens of millions of unique ads? There was only one answer: Let software do it. Thus Google’s second Long Tail technique—dramatically lowering the cost of reaching the market. Its technique is based on a simple and very cheap self-service model. Anybody can become a Google advertiser by buying a keyword in an automated auction process where the minimum bid is just $0.05 per click.

Not only is it cheaper for both Google and an advertiser to use the self-service model, but it also results in more effective ads. Google provides tools to customize and test ads to achieve the highest “click-throughs” (when a consumer clicks on the ad and goes to the advertiser’s site), and it’s not uncommon for advertisers to obsessively tweak their keywords and ad copy until they get the results they want. After all, who knows their businesses better than they do?

The effect of this model has been to extend Google’s advertising business farther down the tail than any company ever has. Today, there are thousands of small Google advertisers who had never advertised anywhere before. Because of the self-service model, the measurable performance, the low cost of entry, and the ability to constantly tweak and improve the ads, advertisers are flocking to this new marketplace. They don’t have to have their arms twisted; no human at Google need ever contact them at all. The result: fewer employees and a model that is as efficient in the tail as it is in the head.

Finally, Google did the same for publishers. Traditionally, there were only two significant ways for Web publishers to make money from advertising. They could either hire their own ad sales forces and court likely advertisers, or they could join an ad network and take whatever they were given at rock-bottom prices. Google’s insight was

that the same relevance-finding technology that could match the right ad with a keyword search could also put the right ad on a third-party content site.

Today, whether you’re the

New York Times

or a blog, you can put a couple lines of HTML code on your site and it will display Google ads—targeted to whatever content you’re providing. Again, it’s self-service: no permission or phone call required. Every time an ad is clicked on, the advertiser pays Google, and Google passes some of the money on to you.

Google doesn’t care whether you’re a professional or an amateur, or how narrow or broad your content may be. If the ads aren’t working, Google will automatically replace them with different ads to see if they work better. Because the pages (“inventory”) cost Google nothing, it can afford to wastefully run ads that no one ever clicks on—the “opportunity costs” of the lost potential revenues are borne by the third-party publisher. It’s a remarkable way to extend the advertising market down the Long Tail of publishing, which includes hundreds of thousands of blogs.

At Google’s first shareholders meeting, CEO Eric Schmidt elaborated on why he describes Google’s mission as “serving the Long Tail.”

He started by showing a slide of a powerlaw with dollars on the vertical axis and people on the horizontal one. Wal-Mart was at the very head. The number “6 billion” was at the end of the tail. Schmidt explained:

We took a look at our market last year and asked ourselves: “How are we doing?” If you look at the advertiser, the market we’re in from the largest companies—Wal-Mart—in the world, all the way down to the smallest companies in the world, the single individual. We call this The Long Tail. A lot of people have been talking about it—it’s a very interesting idea.

We looked at this and we said, “We’ve been doing really well up until now in the middle part of this—well-run, mid-sized businesses, smart people solving interesting problems. But how well do we do against the problems of the very largest customers?” So last year we brought out a whole suite of tools for very large advertisers who can use our services in all of their divisions to generate lots and

lots of revenues because, of course, in our model the advertising drives predictability, it drives conversions, and so forth.And what about the individual contributor, the small business, the company where Joe or Bob is the CEO, the CIO, the CFO and the worker and the support person—a one-person company, a two-person company, a three-person company? We built a whole bunch of small, self-service tools which allowed them to almost automatically use this service.

So [we went] in both directions. By going to the bottom with self-service, we were able to reach advertisers who fell below the threshold of traditional advertising. And by going all the way to the top, we were able to capture very large and historically undeserved businesses as well as a whole new area that never had access to these kinds of online services.

Schmidt later explained to me how these millions of small to mid-sized customers represent a huge new Long Tail ad market:

The surprising thing about the Long Tail is just how long the Tail is, and how many businesses haven’t been served by traditional advertising sales. The recognition that businesses such as ours show a Pareto distribution appears to be a much deeper insight than anyone realized. It’s something that scientists have known for a long time, but it’s never gotten any attention. When we looked at our business, we concluded that we built a model that works particularly well in the middle of the curve. After reading the [original

Wired

] article, we looked at the Tail and asked ourselves, “How are we doing against this opportunity?”Take a Pareto curve of the world’s businesses, ranked by revenue. Number one is Wal-Mart. So what is the last entry? It turns out it’s a person in India with a basket selling something they made. The area under that curve, which includes about a billion people, is essentially the world’s GDP. So start at the bottom and move up the curve until you’ve got people with an Internet connection. They’re reasonably educated, they’re a small business, and they want to market their goods. And we ask ourselves, “What benefit can our model bring them to increase their revenues?” And the answer is that if we let them do business outside their own villages, they’re reaching a

larger market, have got more suppliers, better price competition, and so on.There are a lot of reasons why this is slow to happen, mostly having to do with infrastructure. So let’s say for the purpose of argument that we don’t focus on 90 percent of the people. That still leaves 100 million people. The numbers are so large that you can lop off a large chunk and it’s still a huge market.