The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit (27 page)

Read The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit Online

Authors: Lucette Lagnado

The congregation was booming. New immigrants descended on it day and night. They prayed in the exact way they had in Egypt, determined to allow nothing to change, despite the fact that they now lived thousands of miles from Cairo.

Â

AN ENTERPRISING PAIR OF

brothers began baking pita bread and delivering it to homes up and down Bensonhurst. Morris and Joshua Setton discovered there was an eager clientele willing to spend what little they had to avoid eating white bread. They later opened a grocery store of their own that stocked only Middle Eastern delicacies, realizing early on that merely eating the hot round loaves of pita was a crucial step in retrieving our lost life.

That was the goal now: even more than forging ahead in America, we wanted to replicate what we had left behind in Egypt.

Grown children were encouraged to marry other Levantine Jewsânot Americans, not even other American Jews. Mothers taught their daughters their favorite recipes so they would be preserved and passed on, and their children and grandchildren would dine on the same foods generations of families had enjoyed, a cuisine that mingled the best of Syrian and Egyptian traditions, the sweet fruity passion of Aleppo and the garlicky oniony zest of Cairoâstuffed grape leaves, stewed okra in lemon and tomato, pockets of lamb filled with rice and pistachios, meatballs in sour cherries.

Assimilation?

It wasn't a word we knew or cared to learn, and my father, finally reunited with his own people, was enjoying a modicum of peace and contentment. That was also why he stayed longer and longer at the Congregation of Love and Friendship, not deigning to come home.

It was also, of course, why my sister left. She now lived in a tower high up in the sky in Queens, a part of New York I'd never visited and that sounded distant and foreign. Her rebellion was nearly complete. She had moved out before getting married and against my father's wishes, and she had even sidestepped the unspoken rule about living in a ground-floor apartment, as had always been the tradition in our family starting with Malaka Nazli.

How foolishâand hopelessâto try to reproduce a vanished world, Suzette thought. It depressed her, this effort to build a Cairo-on-the-Hudson. There was nothing in common, she felt, between those humdrum streets of one- and two-family homes and itty-bitty shuls of Brooklyn and the energy and joy and magnetism and life that could be

found in even the shabbiest Cairo alleyway. It was altogether pathetic, this attempt to recapture the past through groceries and synagogues.

Suzette remembered an exuberant culture where religion mattered, but so did going out at night and reveling in all the Levant offered. Our father, who now all but lived at shul, was the prime example of this dual existence, where faith and ritual had in no way hindered his ability to lead a rich and pleasure-filled life. In Egypt, it was easy to be religious and worldly at the same time, but that seemed an impossibility here in America.

It was as if you arrived and were ordered to choose one door or the other, not both.

The biggest missing ingredient was glamour. It had been the defining quality of Farouk's Cairo in the 1930s and '40sâthe elegant British officers, their beautiful mistresses, the passion for dancing, the insistence on going out all night every night. Even after the revolution, there was still an allure to life that couldn't be obliterated by even the most heavy-handed and ruthless military rule. Restaurants continued to stay open late, and people still didn't dine till midnight, and then they went out dancing or merely sat back to watch the belly dancers.

New York, supposedly the greatest city on earth, seemed to be limited to ten or twenty blocks that were drab, functional, and utterly devoid of style.

The moment we arrived, Suzette had sought out a dear friend from Egypt, Marcelle, who was also in Brooklyn. Marcelle had been a wild child, very brainy, very chic, the archetypal party girl. But somewhere on the way to New York, she had undergone a transformation. Shortly after settling here, Marcelle became engaged to a very devout man, and affected the habits and garb of religious American women. She changed her clothes and even her name; instead of Marcelle, she called herself “Adeena.” On the eve of the wedding, she was preparing to cut her hair and don a wig.

Suzette was stunned when she saw her irrepressible girlfriend wearing a long, modest dress and behaving deferentially toward her fiancé.

For Marcelle's wedding, my sister wore a sleeveless sheath. The moment she entered the synagogue, a group of women rushed over in a panic to drape her shoulders with a sweater or shawl. Under no

circumstances, they said, could her arms be bare. That was when she'd sworn to herself that she would leave, and have nothing to do anymore with this community of expatriates who called themselves Egyptians but bore no resemblance whatsoever to the people she had known back in Egypt.

A couple of weeks after my sister moved out of my room on Sixty-sixth Street, my mother moved in. She took over the narrow steel cot left vacant by Suzette.

I didn't even question our sleeping arrangements. I took it for granted that my parents no longer shared a room; they hadn't even on Malaka Nazli. At first, it seemed necessaryâwe simply had no space. But as one by one my siblings left, and they continued to sleep apart, I realized that their refusal to occupy the same bedroom was part of a deeper mystery I could never hope to grasp as a little girl.

Â

EACH MORNING, I LEFT

hand in hand with my mom for PS 205, the small public school around the corner. She refused to let me go alone, despite the short distance, and I cringed because we attracted attention. Only when I had pushed the door open would she relinquish my hand and kiss me good-bye.

I was intensely aware of the differences between me and the other children. It wasn't simply my broken and heavily accented English. There was also the way I looked and dressedâlike a Parisian

lycéene

who had landed in working-class Brooklyn.

My mom loved to dress me like the idealized Parisian schoolgirl of her imagination, sending me to school in navy blue sweaters and matching plaid pleated skirts, though of course, back in Paris, confronted with real French schoolgirls, I dressed like an Egyptian.

I marched out of the house looking as if I were on my way to some swank school in the sixteenth arrondissement. Alas, my wardrobe only set me apart once again from my classmates, the little girls who came in colorful dresses with wide flare skirtsâclothes hand-sewn by their mothers, elaborate and showy, and lined with ribbons and bits of velvet trim.

“They are so

fellahi,

” my mom exclaimed when I expressed a longing to look like my schoolmates. To compare someone to an Arab peas

ant was her most searing put-down. To Mom, these families of seamstresses and housepainters and sanitation men were merely fellahin, although I noticed when I went to their homes that they lived far more comfortably than we did.

Loulou as a young schoolgirl in Brooklyn.

I wasn't sure how we were superior to them. We were the ones who were poor and struggling desperately; wouldn't that make us fellahin?

Lunch was also an ordeal. I noticed that most of the children carried lunchboxesâsmall, sturdy, efficient affairs, made of metal. Inside, there'd be a sandwich consisting of two slices of white bread filled with tuna or bologna or ham or cheese. My fare came in a brown paper bag, typically a fresh roll purchased at dawn by Mom from the Italian bakery around the corner and stuffed with a Hershey bar.

My classmates peered at my lunch and then at me. “Is that a chocolate sandwich?” they asked, their eyes widening.

I nodded yes and took a big bite. I found it absolutely deliciousâthat is, until I realized they found it awfully strange, this

pain au

chocolat

lunch of mine. Self-conscious, I asked her not to make them anymore.

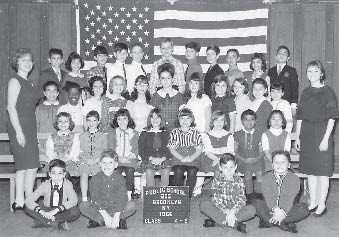

Loulou's American class.

I wandered around my new school, shy as could be in my pleated skirt and sweater sets. Classes, at least, were simple. I was more than prepared for the rudimentary arithmetic, reading, and science that constituted an American elementary school education. My problem was gym. I had never played sports in Cairo or Paris, so the sudden emphasis on physical fitness took me completely aback. I wandered through gym classes in a fog, volunteering for nothing.

Without explaining why, Mom instructed me never to reveal I came from Egypt. I told anyone who asked that I was from Paris. To my teachers, this made me a charming novelty, “that little French girl,” and even my closest friends didn't know the truth. Yet I often felt I was living a lie, burdened with a dark secret that was bound to surface: that I wasn't French at all, that I was born in Cairo.

Â

AFTER SUZETTE LEFT HOME,

I noticed that my brothers also seemed to drift away. César, our sole means of support since my sister had moved out, worked during the day and then went off to school and after that to his mysterious nightlife, so that I was asleep by the time he came home. Isaac spoke of joining the U.S. Air Force. I was secretly pleased at the prospect of his leaving. He and I were always clashing, and unlike my oldest brother, who tended to be protective, I found Isaac, six years my senior, caustic and combative.

While César was more docile, and closer to my dad, even he seemed increasingly removed from the religious practices that had been so central to our life. My father's worst fears about America were coming to pass. He'd order my brothers to pray. They'd merely shrug and go their own way.

Even my mother was rebelling: outfitted with a new pair of dentures, Sylvia Kirschner's last legacy, she kept hinting that she wanted to go out and find a job. Her first declaration of independence came when she decided to abandon the Congregation of Love and Friendship. She'd tried valiantly to fit in, but the area where women sat, a cramped space behind a wall, was so dismal, and it was often impossible to find an empty seat or follow the service. Even worse were the busybodies who kept grilling Mom on Suzette's whereabouts. “Is she married yet?” they'd ask, while the less kindly among them posed the same question with more edge: “She

isn't

married yet?”

My mother would manage a valiant smile and blithely insist that her daughter, only twenty years old, was too busy going to college and minding her studies. None of the women believed her.

And so we fled a congregation where we had found neither love nor friendship. My mom took me by the hand one Saturday morning, and we walked past Dad's synagogue and didn't stop until we arrived at another house of worship called the Shield of Young David. It was slightly more diverse; while worshippers were also from the Levant, there were Turks, Moroccans, Tunisians, Algerians, even Mexicans, in addition to the Egyptian and Syrian Jews.

It was also roomier, with an airy women's section whose graceful filigreed wooden partition made it possible to follow the entire service

without straining. Taking her place in the first row, with me at her side, my mom sat down and never looked back. She began to make friends with the women around her. Her closest friend, a Moroccan immigrant she called Madame Marie, had a daughter, Celia, who was slightly older than me. Mom and Madame Marie confided to each other their angst about raising daughters in America.