The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit (29 page)

Read The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit Online

Authors: Lucette Lagnado

His heartâand mineâwas with the Zambian copper mines. When I asked him about the strange-sounding stock, he winked and made it sound as if that single investment held so much promise that any day now we would find ourselves the owners of our very own African copper mine.

My mother didn't share his fascination. “Ton père jette son argent,” she'd say loud enough for him to hear; Your father throws away his money.

Dad loved Dow Jones and the industrial average. But as much as he reveled in the rock and roll of the market, and believed in the implicit promise of

la bourse,

as he insisted on calling it, Edith loathed the very idea of investing, and any time she talked about stocks and bonds, it was with contempt. The stock market was gambling, she believed, pure and simple. She saw it as a dangerous indulgence by a grown man living in hardscrabble Brooklyn, who still thought of himself as a carefree Cairo boulevardier.

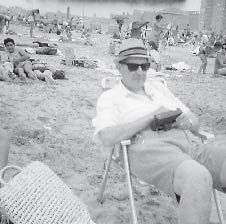

My father had never stopped loving games of chance. Even when he'd join us at the beach, carting slowly his green-and-white beach chair until he found us, he barely dipped his sore leg in the ocean. Instead, seated in his beach chair, a cold soda in his hand, he continued to pore over the pages of the

Wall Street Journal

or the stock listings of the

New York Times,

anxious to see how his investments were faring, as diligent a monitor of the market as any captain of industry or Wall Street swell.

Â

THERE WAS ONE MORE

stop to make. Together, we boarded the subway for the short ride from Canal Street to Delancey Street, in the heart of the Lower East Side. We didn't have far to walk, but by the late afternoon, my father's limp had become more pronounced, and we kept stopping so he could rest. I asked if I could help carry the brown box, but he refused. I was never allowed to lug either the box or the precious manila envelope.

Years before it became part of the downtown revival, the area near Delancey Street had a more animated feel to it than the textile district. It was thronged, and the stores seemed to offer a thousand different wares, which they exhibited outside their shops on the sidewalksâfrom men's hats and fine women's clothing to pots and pan and other house-wares. Many of the stores were run by men in skullcaps, Orthodox Jews, many of them Holocaust survivors and their children, who had brought the skills of the old Eastern European shtetl to the Lower East Side.

Leon at the beach, Brooklyn, 1960s.

I followed Leon to a dingy back street of tenements, where the shops were so small, they didn't even have signs to identify them. One especially careworn storefront required us to walk down a few steps and push open a large metal door. It was a factory, where I saw women hunched over sewing machines in a cramped, windowless room. They looked up briefly as we walked in, then went back to their stitching. My father made a beeline for the owner.

The two seemed to know each other well. The factory made ties, and my father had come to restock his supply. The owner brought out several samples from his newest line and spread them out on a small counter. They all seemed beautiful to me, and I nodded eagerly as my father indicated his preference for this style or that. Finally, Dad asked the owner: Were there labels on the ties?

The owner sheepishly admitted he hadn't gotten round to that.

My father was visibly upset. “Monsieur, I'll have to come back another day,” he said, and started to leave.

That is when the owner signaled to an older woman who sat at the head of a large rectangular table, where at least half a dozen seamstresses were ensconced at their machines, and gave her rapid-fire orders in a language I didn't understand. She nodded. He turned to my father and assured him that the work would get done if we waited a bit.

That is when I understood. The ties that I had admired for so long hadn't been imported from Paris or Rome. They were made here, in this small dusty sweatshop somewhere between Essex and Delancey, then had phony labels proclaiming their exotic provenance attached by one of these women bent over their Singer sewing machines.

And they weren't even made of silk.

We walked out with a new brown cardboard box stuffed with a fresh supply of ties that bore the elegant but deceitful labels. My father seemed so buoyed by his brand-new stock that he cornered a group of men on the street and was able to make a sale.

As we walked toward the subway with our inventory, I avoided asking about the “imported” ties. Instead, I pressed my father about what I should do with my own life. At nine, I was restless and ambitious beyond my years. I wanted to be a detective, a secret agent, a master spy. I wanted to travel around the world and return to all the cities we had fled. I wanted to hold an important job and make large sums of money and take taxis constantly.

“You can have a little job,” Leon said in that mild tone that masked a definite intensity.

We both knew that it was common for women to work in America. My own mother was still flirting with the idea of employment. She had received one lucrative job offer from Grolier, the prestigious French publishing house.

She had actually dragged me to the interview, much to the surprise of the senior editor who had asked Mom to come in after receiving her charming and mellifluous application letter, in which she touted her passion for books and her longing to work in the literary world. My mother hadn't wanted to leave me home alone, but hiring a babysitter would have been unthinkableâI never once was left with one. And so she took me along.

I'd sat silently, afraid to breathe as the Grolier editor frowned and

made some comment to the effect that she hoped I wasn't a noisy child. Mom had been able to reassure her that I would keep still, and went on to impress her with her unusual credentialsâa knowledge of literature that went back to her Cairo childhood, followed by a stint as a teacher and librarian at a prestigious boys' school called the Ãcole Cattaoui Pasha. She even told of the Keyâthe Key to the Pasha's Library.

An offer came days later. My mother was stunned. She had never believed Grolier would actually want to hire her, let alone pay her so bountifullyâbeyond our wildest imaginings. The job came with a title, entrée into the fashionable Manhattan neighborhood where Grolier was situated, and a salary that seemed to us almost absurdly high. It happened to be greater than what my older brother and father together were earning.

Most important of all, she would be working once again with books.

Still, after a great deal of agonizing and soul-searching, Mom turned Grolier down. It was in part her own inability to break loose, to free herself from her role as a wife and housewife. Then there was her fear of defying my father. She knew, of course, that he didn't approve of women working: hadn't she quit a job she loved, working with the pasha's wife, when she married him?

It was too ingrained a part of Egyptianâand Syrianâculture: a woman, especially a married woman, doesn't work. We were no longer in Egypt, and my father couldn't support any of us anymore, but that was almost beside the point.

Yet she was clearly ambivalent. There was a piece of her that loved books even more than marriage and a family. She also knew how perilous our finances had become since Suzette's departure. Now, suddenly, she was being handed a chance to reverse our shaky fortunes. There was no question that the position at Grolier would have propelled herâand usâinto the middle class and, if she had done well, perhaps the upper middle class, an almost unheard-of achievement for a refugee family. But she was heeding an unspoken rule about women and work, no matter how antiquated it felt in America, where women were entering the workplace by the millions and society was changing to accommodate them.

Only my father didn't change. He cast a dubious eye on all these developments. Whoever heard of a woman working? he chuckled. It was part of his inviolate code of conduct that womenâcertainly a wife or a daughter of hisâshould steer clear of the rough-and-tumble business world.

I asked him, if I had to work, what should I do?

“You can have a little job,” he said finally. The “little job” he had in mind took me aback. He suggested that I open a flower shop.

“But you don't even like American flowers,” I pointed out. His idea seemed out of left field. I had no interest in plants or flowers. He didn't seem to hear me.

“Loulou, you can open your own flower shop,” he repeated, and there was a faraway smile on his face, as if he were smelling the roses of Egypt. But his final piece of advice on that summer day was sparse and to the point: I had to marry, and marry wellâ

un banquier,

a banker.

I had to find a man who would give me back all we had lost when we left Cairo.

I

n the weeks leading up to Passover, the holiday when it is forbidden to eat bread, my mother reenacted a ritual with me that dated back generations. She enlisted my help in the ceremony known as the Sifting of the Rice, in which each and every grain of rice had to be pristine, cleansed of all its impurities.

Mom was in the throes of a massive spring cleaning, mopping and scrubbing every corner of our apartment. Even a small crumb, left behind by mistake, would be a desecration. It also risked unleashing my father's outrage. I followed her around, mother's little helper, lugging buckets filled with hot soapy water that she needed to wipe the walls and windows. Sometimes, when she wasn't looking, I joyfully flung the water onto the panes of glass and the Formica countertops, letting the suds drip all over the floor. I would take a cloth and, seeking to emulate her, would scrub scrub scrub scrub with a passion and abandon I never brought to housework.

Not that I was ever expected to do much of it.

It was an unspoken commandment at home: “Loulou shall do no

menial chores.” I was the envy of my friends, who were constantly being called upon by their moms to wash dishes and dry dishes, to set the table and clear the table. I wasn't asked to do so much as rinse a single glass, or sweep, or dust, or make my own bed, or anyone else's.

This was largely my father's influence, his unwavering conception of how a daughter of his should be raised. In Cairo, where there had been an endless supply of maids to attend to every aspect of running a house, a pampered daughter was never expected to help.

There were no maids in America, or none that we could afford, but my father still objected to seeing me do chores that had been the purview of

les domestiques.

He thought nothing, however, of having my mother perform all the household tasks. Such was the hierarchy in an Oriental household, be it Muslim or Jewish: the father as patriarch came first; his rule was absolute. The sons came next. They wielded almost as much authority, and were treated like young princelings. The daughters commanded their own sphere of influence by virtue of their closeness to the father.

The mother came dead last; her role was to cater to everyone else.

Still, Mom didn't quarrel with my dad about what I should and shouldn't do. She agreed that I should be spared mundane tasks, and encouraged rather than resented my privileged status. My upbringing was one of the few areas in which my parents were seemingly in perfect accord. But their motives were starkly different. My father expected me to follow a traditional path of marriage and a family, but was confident that any man he'd embrace as a son-in-law would provide me with all the help I needed. He didn't discourage my studies at school, figuring they could enhance my desirability as a mate. But he saw no need for me to learn to cook and clean.

From time to time, he alluded to the dowry he was amassing for me, suggesting I would one day have my pick of husbands.

My mother had a different rationale for encouraging my sloth. She wanted to make sure I had

none

of the skills that would help me cope as a wife and mother. In a sense, she was the quintessential passive-aggressive. Cowed by my father, she also had a profound rebellious streak, which showed itself in the way she was raising me. She shuddered to

think that I would gravitate to a life of domesticity, that I, too, would become a prisoner of Malaka Nazli (or its American equivalent).

God forbid, she would tell me, that I would grow up and have to cater to some man and an ungrateful brood of children.

For good measure, she'd add: “Never marry a Syrian.” She suggested that Syrian men were handsome and seductive, but also bossy and narcissistic. They treated women like slaves, she told me. I didn't dare challenge her, and even at a young age, I found myself looking at Syrian men warily.

When I developed a crush on my friend Diana's older brother MauriceâSyrian, to be sure, but with wonderful blue-green eyesâI worried lest I be forever a captive of his charms.

Mom's strategy to discourage me from the life most of my friends dreamed of was simple and diabolicalâshe refused to teach me any of the basics. I wasn't shown how to clean a room or make a bed. I didn't learn how to fix lunch or dinner. Of course, that also meant I was never shown how to prepare the wonderful dishes she had mastered during those rough early years with Zarifa. Mom had emerged as a wondrous cook. Night after night, she prepared foods that were redolent of the Levant, and that I would never taste again because I'd never been shown how to make themâtender pockets of lamb stuffed with rice and pistachios and cooked for hours in the stove until the meat seemed almost to melt off the bone; okra flavored with so much lemon and garlic, the entire kitchen was filled with the scent.

I was left to my own devices. I slept late, read novels, and languished about the house while she scurried about from errand to errand, chore to chore.

The exception was Passover, when the workload was so overwhelming she couldn't cope on her own. I didn't mind pitching in because even the most ordinary household tasks seemed imbued with a higher purpose. Besides, my mother seemed panic-stricken, though I wasn't sure if it was a fear of God or a fear of my father that motivated her.

Every Passover, Edith took me by the hand to the basement, where the twenty-six suitcases from Egypt remained, neatly stacked. In what had become a ritual, we opened one after the other in search of the

ancient metal box I viewed as the source of all the mysteries and pleasures of the holiday.

Round like a hatbox, it was made of a burnished dark gray steel that had weathered all our voyages before finally ending up in our apartment in Brooklyn: from Cairo to Alexandria, Alexandria to Athens, Athens to Genoa, Genoa to Naples, Naples to Marseilles, Marseilles to Paris, Paris to Cherbourg, Cherbourg to Manhattan, and, at last, Manhattan to Brooklyn.

The box lay undisturbed deep inside the brown leather suitcase that had been its first home, protected by Mom's astrakhan fur coat, her wedding gown, and other layers of ancient clothing.

I half expected ghosts to come flying out of the box, a djinn in a great puff of smoke. Instead, I only saw the same lovely porcelain dishes, wrapped in individual paper, we had put away the year before. There were china cups, small liqueur glasses, and sets of silverwareâreal silver, not the 25-cents-a-fork variety we bought from Woolworth's.

Many of the items were almost a century old. They had belonged to my grandmothers Zarifa and Alexandra, and Mom treated them as if they were holy relics, fingering them ever so gently. There were teaspoons so minuscule, they would fit inside a dollhouse. The spoons, including Zarifa's small spoon made of gold, had a unique function: they were used to sample the

haroseth,

the maroon-colored jam made from crushed dates and raisins that was the centerpiece of the Passover meal.

Though I was useful in helping Mom pick through suitcases and dust off silverware, nowhere was I more needed than handling rice. Back in Cairo, when rice came in twenty-kilo sacks replete with stray bits of grain or straw, it was important to sanitize it for the holiday. This was considered such a crucial task that the typical Jewish housewife took it upon herself to inspect the rice no fewer than seven times, each more rigorously than the last. Nor could the work be entrusted to the maids. Even in the relative comfort of Egypt, where almost every chore could be turned over to a hireling, women such as my mother performed this task themselves, or else with other family members.

Admittedly, some of the more progressive families went over the

rice only four times. Edith insisted on seven. In Cairo, Mom had “hired” Suzette and César to help her out, installing them at the large dining room table and paying them a few piasters for the work.

But here in America, when our rice supply consisted of the tightly wrapped cardboard packages of Carolina or the even pricier Uncle Ben's, we had on our hands a product that had already been processed, purified, homogenized, sterilized, and hermetically sealed.

What impurities could those milky white granules contain? What could possibly be sinful about eating Uncle Ben's?

Edith warned me to be careful as she spread a large white sheet on the dining room table, put me in a chair by her side, then forced me to dump out the contents of box after box so that the table was covered with mountains of rice. Each of us began the task of going through each grain of rice, separating the pure white grains from the blemished brown ones. I would put rice into a large bowl and proceed to review a handful of rice at a time, relishing how the grains felt as they slipped through my fingers.

I never questioned the necessity of what we were doing. It never occurred to me to wonder why we needed to peer at thousands upon thousands of individual grains of rice, one by one, one by one. I never challenged any of the rituals we followed at home, they were such an essential aspect of who we were as a family.

And among the scores of observances and sacraments that we tried to uphold through our peregrinations, from our home in Cairo to our refugee hotel in Paris, the welfare hotel in New York, and an immigrant community in Brooklyn, the Sifting of the Rice was the one that we never compromised, because it was permeated with the most sacred aura.

My mother would smile as I handed her bowl after bowl of the purified rice. I had carefully examined each one precisely seven times to make sure there wasn't the slightest imperfection. We sifted through twenty pounds or more, for that was how much the family would consume within the first couple of nights of the holiday.

When I grew older, and learned that my American peers, the Jews whose ancestors hailed from Eastern Europe or Germany, didn't eat

rice at all during Passover because they considered it tabooâalmost as much of a sin as eating breadâI was completely taken aback.

What care we had taken to make sure the rice we ate would pass God's own inspection!

And then there were the friends and acquaintances who startled me in a different way, by eating whatever they wanted on the holidayâeven bread. Whatever happened, I wondered, to worrying over the integrity of a single grain of rice?

The Passover marathon culminated in a ghostly candlelit inspection tour conducted by my father. Late at night on the eve of the holiday, Leon, clad in his pajamas, holding a tall white candle in one hand and a prayer book in the other, led a nocturnal procession. As he shuffled from room to room and from corner to corner, Mom and I followed anxiously behind him, holding our breath as he peered inside closets, opened kitchen cabinets, rifled through bedroom drawers, and bent down to examine the floor, checking for stray crumbs. He looked like one of those detectives from those 1940s film noirs going over a crime scene with a flashlight, searching intently for any evidence of wrongdoing.

He was as rigorous as these mythical old Hollywood detectives. While there was a piece of me that enjoyed the theatrical aspects of the ghostly inspection, I realized this was deadly serious business for my father. Mild-mannered in most of his dealings with us, he was intransigent, uncompromising, and almost tyrannical when it came to religion. There were no shortcuts to faith, my father believed, no rules that could be bent or broken.

My mother alternated between trying to please him and rebelling against his despotic ways.

“Fanatique,” she would cry out.

But she usually retreated, either because she was cowed by him, or because she, too, became persuaded that God himself cared that our little Brooklyn apartment was spotless for the holiday, and that He personally wanted to make sure the steaming platters of rice that would accompany the fragrant meat stews, or served alongside the thousand exotic delicacies she prepared, adhered to the highest standards of heaven and earth.

Â

OF ALL THE ARCANE

rituals and ceremonies I associated with the holiday, none was more sacred to me than shopping for a new dress.

My mom spent months carefully putting money aside so I could have a proper outfit to wear that single week of the year. For a holiday that signified renewal, where closets were emptied and shelves were stripped bare and floors were scrubbed and old food was mercilessly cast aside, it would have been unthinkable not to have a sparkling new wardrobe.

No other occasion, not even my birthday, warranted as major an expenditure.

La Eighteen,

as Mom liked to call Eighteenth Avenue, with its cheery array of children's stores catering to families with small budgets, was our choice destination. It was my mother's favorite shopping venue, and in the course of walks either alone or with me, she had befriended most of the storeowners and was able to converse in fluent Italian she'd mastered as a child with those who hailed from Naples or Calabria.

La signora francese,

they called her, or simply

la signora,

and beckoned her to enter their establishments, though she could rarely afford to make a purchase.

As I looked forward to turning ten, I was no longer willing to defer to my mother in the selection of this all-important dress. In the past, she had wielded considerable influence, nudging me toward one or another outfit because of budgetary constraints or her own definite tastes. This time, I was determined to buy a dress entirely of my own choosing.

I longed for the years when my shopping expeditions were with my father, who had exerted almost no influence on what I wanted to buy. He'd simply stand aside, chatting with the salesgirlsâonly the pretty ones, of courseâas I fluttered about a store, trying on this dress or that. He became involved only when it was time to pay the bill.

My dad no longer took me shopping: the responsibility was now left entirely to my mother. I found her rather a sorry substituteâopinionated where he had been open-minded, penny-pinching where he had been munificent. As if sensing that she was falling short, she announced that she had in mind a special destination for my all-important holiday purchase.