The Marriage Book (7 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

HUMAN, ALL TOO HUMAN

, 1878

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) is often credited with planting the seeds of modern philosophical inquiry and sometimes assailed for providing—however unwittingly—the underpinnings of fascism. The prolific German philosopher was ill, either physically or mentally, for much of his life and never married. But he included maxims about many aspects of personal life in

Human, All Too Human

, one of his earliest works.

This was aphorism number 406, preceded by one called “Masks” and followed by one called “Girlish dreams.”

Marriage as a long conversation.—When entering into a marriage one ought to ask oneself: do you believe you are going to enjoy talking with this woman up into your old age? Everything else in marriage is transitory, but most of the time you are together will be devoted to conversation.

ELLA CHEEVER THAYER

WIRED LOVE

, 1880

Ella Cheever Thayer (1849–1925) subtitled her novel

A Romance of Dots and Dashes

and drew for it from her experience as a Boston telegraph operator. The passage below, so bizarrely prescient, was written just four years after Alexander Graham Bell’s patent of the telephone.

We will soon be able to do everything by electricity; who knows but some genius will invent something for the especial use of lovers? something, for instance, to carry in their pockets, so when they are far away from each other, and pine for a sound of “that beloved voice,” they will have only to take up this electrical apparatus, put it to their ears, and be happy. Ah! blissful lovers of the future!

EDITH WHARTON

THE AGE OF INNOCENCE

, 1920

In much of her writing, Edith Wharton (1862–1937) evoked the manners and morals of the turn of the twentieth century—perhaps never more brilliantly than in her Pulitzer Prize–winning novel of New York society,

The Age of Innocence

. Newland Archer, dutiful fiancé and then husband to May Welland, is passionately and guiltily in love with her cousin, Ellen Olenska. This love is neither consummated with Ellen nor discussed with May, and it is only at the end of the book, in this memorable scene with his son Dallas, that it becomes clear to Newland how little his silence has succeeded in concealing anything.

Fanny is Dallas’s fiancée. The line break and ellipsis are the author’s.

Archer felt his colour rise under his son’s unabashed gaze. “Come, own up: you and she were great pals, weren’t you? Wasn’t she most awfully lovely?”

“Lovely? I don’t know. She was different.”

“Ah—there you have it! That’s what it always comes to, doesn’t it? When she comes,

she’s different

—and one doesn’t know why. It’s exactly what I feel about Fanny.”

His father drew back a step, releasing his arm. “About Fanny? But my dear fellow—I should hope so. Only I don’t see—”

“Dash it, Dad, don’t be prehistoric! Wasn’t she—once—your Fanny?”

Dallas belonged body and soul to the new generation. He was the first-born of Newland and May Archer, yet it had never been possible to inculcate in him even the rudiments of reserve. “What’s the use of making mysteries? It only makes people want to nose ’em out,” he always objected when enjoined to discretion. But Archer, meeting his eyes, saw the filial light under their banter.

“My Fanny—?”

“Well, the woman you’d have chucked everything for: only you didn’t,” continued his surprising son.

“I didn’t,” echoed Archer with a kind of solemnity.

“No: you date, you see, dear old boy. But mother said—”

“Your mother?”

“Yes: the day before she died. It was when she sent for me alone—you remember? She said she knew we were safe with you, and always would be, because once, when she asked you to, you’d given up the thing you most wanted.”

Archer received this strange communication in silence. His eyes remained unseeingly fixed on the thronged sunlit square below the window. At length he said in a low voice: “She never asked me.”

“No. I forgot. You never did ask each other anything, did you? And you never told each other anything. You just sat and watched each other, and guessed at what was going on underneath. A deaf-and-dumb asylum, in fact! Well, I back your generation for knowing more about each other’s private thoughts than we ever have time to find out about our own.—I say, Dad,” Dallas broke off, “you’re not angry with me? If you are, let’s make it up and go and lunch at Henri’s. I’ve

got to rush out to Versailles afterward.”

Archer did not accompany his son to Versailles. He preferred to spend the afternoon in solitary roamings through Paris. He had to deal all at once with the packed regrets and stifled memories of an inarticulate lifetime.

After a little while he did not regret Dallas’s indiscretion. It seemed to take an iron band from his heart to know that, after all, some one had guessed and pitied. . . . And that it should have been his wife moved him indescribably.

EVAN CONNELL

MRS. BRIDGE

, 1959

Mrs. Bridge

was the first novel published by Evan Connell (1924–2013), and it was both a critical and commercial success. In a spare but evocative voice, it tells the story of a midwestern American woman whose conventional marriage leads to a crisis of identity and a search for love.

Connell would go on to write a companion novel,

Mr. Bridge

, in 1969, as well as nearly twenty other books, including the bestselling

Son of the Morning Star

in 1984.

As time went on she felt an increasing need for reassurance. Her husband had never been a demonstrative man, not even when they were first married; consequently she did not expect too much from him. Yet there were moments when she was overwhelmed by a terrifying, inarticulate need. One evening as she and he were finishing supper together, alone, the children having gone out, she inquired rather sharply if he loved her. She was surprised by her own bluntness and by the almost shrewish tone of her voice, because that was not the way she actually felt. She saw him gazing at her in astonishment; his expression said very clearly: Why on earth do you think I’m here if I don’t love you? Why aren’t I somewhere else? What in the world has gotten into you?

Mrs. Bridge smiled across the floral centerpiece—and it occurred to her that these flowers she had so carefully arranged on the table were what separated her from her husband—and said, a little wretchedly, “I know it’s silly, but it’s been such a long time since you told me.”

Mr. Bridge grunted and finished his coffee. She knew it was not that he was annoyed, only that he was incapable of the kind of declaration she needed. It was so little, and yet so much.

BARRY LEVINSON

DINER

, 1982

Barry Levinson (1942–) wrote and directed

Diner

more than two decades after the year in which it was set, but the film was hailed for the way it perfectly captured the bittersweet tensions lurking beneath the surface of relationships in 1959 urban America. In this scene, the recently married Shrevie Schreiber tries to reassure the soon-to-be married Eddie Simmons.

Beth is Shrevie’s wife.

EDDIE: | Shreve, you happy with your marriage or what? |

SHREVIE: | I don’t know. |

EDDIE: | What do you mean, you don’t know? You don’t know? |

SHREVIE: | What? |

EDDIE: | How could you not? You don’t know. How could you not know? |

SHREVIE: | I don’t know. Beth is terrific and everything. But Jesus I don’t know. I’ll tell you a big part of the problem though when you get married—well, you know, when you’re dating, everything is talking about sex, right? Where can we do it? You know, why can’t we do it? Are your parents going to be out so, so we can do it? You know? Trying to get a weekend just so that we can do it. |

EDDIE: | So you can do it. |

SHREVIE: | Everything is just always talking about getting sex. And then planning the wedding, all the details. |

EDDIE: | Details. Shit. |

SHREVIE: | But then, when you get married, it’s crazy, I don’t know. I mean, you can get it whenever you want it. You wake up in the morning and she’s there. And you come home from work and she’s there. And so all that sex planning talk is over with. And so is the wedding planning talk ’cause you’re already married. |

EDDIE: | Right. |

SHREVIE: | So, you know, I can come down here, we can bullshit the whole night away, but I cannot hold a five-minute conversation with Beth. I mean, it’s not her fault, I’m not blaming her, she’s great. It’s— |

EDDIE: | No, of course not. |

SHREVIE: | It’s just we got nothing to talk about. But it’s good, it’s good. |

EDDIE: | It’s good. It’s nice, right? It’s nice? |

SHREVIE: | Yeah, it’s nice. |

EDDIE: | Right. Well, we always got the diner. |

SHREVIE: | Yeah, we always got the diner. |

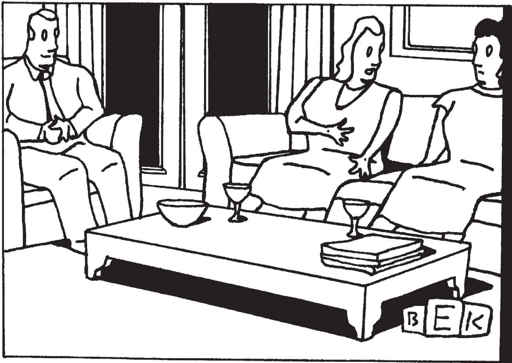

BRUCE ERIC KAPLAN, 1999

Bruce Eric Kaplan (1964–) had his first cartoons published in

The New Yorker

in 1991 and, with the signature BEK, has since contributed hundreds more. Book-length collections have followed, including

No One You Know

and

This Is a Bad Time

, and so has a career as a television writer for

Six Feet Under

and producer for

Six Feet Under

and

Girls

.

Kaplan also wrote an episode for the sitcom

Seinfeld

in which a fictionalized

New Yorker

cartoon editor reluctantly admits he doesn’t understand one of the cartoons he’s published.

“Sometimes I think he can understand every word we’re saying.”

JERRY SEINFELD

WHITE HOUSE TRIBUTE TO PAUL M

C

CARTNEY, 2010

Comedian Jerry Seinfeld (1954–), star and co-creator of the nineties-defining sitcom

Seinfeld

, performed at the White House when Paul McCartney was given the Gershwin Prize for lifetime achievement. In his routine, Seinfeld suggested that the former Beatle’s lyrics have paralleled his life stages, including what Seinfeld deemed marriage songs such as “The Long and Winding Road,” “Fixing a Hole,” and even “Let It Be.”

It’s a beautiful thing, marriage. It’s two people, that’s it. Trying to stay together without saying the words “I hate you.” That is your goal. You never say those three words. You say other things. Things like, “Why is there never any Scotch tape in this house? Trying to tape something up down here!”

“Scotch” is “I.” “Tape” is “hate.” “House” is “you.” But. It’s an improvement.

CONFLICT

ELIZABETH SMITH SHAW

LETTER TO ABIGAIL ADAMS SMITH, 1786

Sister of Abigail Adams, Elizabeth Smith Shaw (1750–1815) had herself been married nine years when she offered this advice to her newly wed niece, Abigail “Nabby” Adams.

The woman who is

really

possessed of superior Qualities, or

affects

a Superiority over her Husband, betrays a pride which degrades herself, and places her in the most disadvantatious point of view. She who values domestick Happiness will carefully guard against, and avoid any little Contentions—the

Beginnings

of Evil—as she would a pestilential Disease, that would poison her sweetest comforts, and infect her every Joy. There is but one

kind

of Strife in the nuptial State that I can behold without horror, and that is who shall excell and who shall oblige the most.