The Marriage Book (71 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

One night as the date was drawing near, I sat in bed flipping through a book on witchcraft rituals. I came across a passage that made my hair stand on end. It described how women

standing in a circle at a Sabbat turn to each other and give each other “the fivefold kiss,” kissing the forehead, eyes, lips, breasts, and genitals. I nearly fell off the bed. “LOUISE!” I shrieked. “We’ve got to get ALL the details on this ceremony!”

The next morning I called our Witch friend and asked for a blow-by-blow account of what was going to happen. I was all right until she got to the part about “anointing the genitals with water.”

“We can’t

do

that,” I said. “Our mothers are going to be there. Besides, I think Louise would faint.”

The Witch was horrified. “You can’t drop it! This is a very important part of the ceremony! I just can’t imagine what the spiritual repercussions might be! It could be terrible!”

“I’ll risk it.”

“You don’t understand. The genitals are very involved in what you’re doing here . . .”

“You’re telling ME!”

“. . . and it could be

tragic

to omit this protective blessing on your sexual union!”

“Do it like the Catholics do—offer up a silent blessing.”

In the end, Witch tradition won out, but only if done with ex-Catholic subtlety.

The women of both our families jumped into the preparations for the tryst with enthusiasm, this being the first tryst in both families’ history. The fathers and brothers took a somewhat dimmer view of the proceedings. Because of their customary lack of enthusiasm for events of a lesbian nature, and because of the customary lack of enthusiasm of many of our guests for men in general, they had not been invited. They reacted to this with customary outrage, half of them “threatening” not to come, the other half threatening to come.

CHECKING OUR CLOSETS

But Louise and I had no time for family squabbles; we busied ourselves with weightier issues, like the What-to-Wear argument. I had always wanted to see her in a tuxedo, and this seemed the perfect time, but she had other plans and could not be moved. When I wailed, “But when will I ever get to see you in a tuxedo if not on this day?” she replied, “The day you bury me.” End of discussion.

Louise’s idea was that we should be “outside of time and fashion and contemporary limitations—we should wear stately robes!”

“Robes?”

“Yeah, you know, like Ben-Hur, El Cid, Diana the Goddess, Helen of Troy.”

“Jesus!”

“That’s RIGHT! Roman togas!”

“Good lord, the witches want to bless my genitals, you want me to dress up like Irene Papas, why did I ever start this thing?”

And with that it hit us: that period of reflection and kicking ourselves known as Prenuptial Jitters. This malady expresses itself in many different forms, all of them desperate. Lesbians, it turned out, are not immune to any of them.

Louise went scurrying off to her shrink to babble, “I love her,

but

. . .” Meanwhile, I surveyed the preparations for the coming tryst, which were in a shambles. Half the women we’d invited weren’t speaking to the other half. The men were still threatening to come. Louise’s aunt, who had promised to help, suddenly decided to get divorced, and so spent all the time she should have been whipping up Roman togas crying instead. Louise and I looked at each other and saw the face of a haunted stranger. We retired to separate gay bars to think things over.

Drinking alone, we missed each other. Coming home to bed, we found again some common ground. Revitalized, we remembered that while neither of us wanted to be a groom, we couldn’t pass up this once in a lifetime chance to both get a bride.

THE DAY OF RECKONING

Faster than you can say “public commitment,” the day of the tryst had arrived. The ceremony itself was short, sweet, and to the point. There were no dramatic surprises, no one popping up to yell, “Stop! She’s got a wife and four kids in Des Moines!” There was just us and the goddess and our families and friends, standing there doing what every lesbian has the right to do: be proud and public about her love. I cannot vouch for my appearance, but Louise looked like a dyke angel, shining from the inside out. We held hands, jumped the broom, and it was done! Applause broke out and the party was on.

WILLIAM GOLDMAN

THE PRINCESS BRIDE

, 1987

The vows in this scene are being hurried by an impending disruption from the bride’s true love. We will forgo any other introductory explanation to say, simply, that if you have never seen this movie, please put this book down and go do so.

IMPRESSIVE CLERGYMAN: | (Clears his throat, begins to speak.) (He has an impediment that would stop a clock.) (And now, from outside the castle, there begins to come a commo- tion.) (Prince Humperdinck, turning quickly, gives a sharp nod to Count Rugen.) |

HUMPERDINCK: | Skip to the end. |

IMPRESSIVE CLERGYMAN: | Have you the wing? |

IRA GLASS

“NIAGARA,”

THIS AMERICAN LIFE

, 1998

Long known as a romantic honeymoon destination, Niagara Falls has also become a favorite for quickie nuptials, with numerous chapels springing up within a bouquet’s throw of the roaring falls. The popular public radio show

This American Life

, hosted by Ira Glass (1959–), presented this account by documentary producer Alix Spiegel of one such wedding.

SPIEGEL: | It’s Catherine and A.J.’s first time, which is a little unusual for the Niagara wedding chapel. Most of their market is second marriages. Catherine and A.J. have driven to Niagara from Pittsburgh with 30 of their friends and family, and are now waiting together with their maid of honor in the welcome area outside the chapel. They all look happy and nervous. They’re laughing and joking, talking about the kinds of things you talk about right before you get married. |

WOMAN 1: | A.J., you still have time to back out. |

WOMAN 2: | No. |

CATHERINE: | He’s calmer than me. |

WOMAN 1: | I know. He’s so calm. That’s cool. |

CATHERINE: | I should have gone to the bathroom. |

SPIEGEL: | Chris, the owner and manager of the Niagara chapel, comes in to tell Catherine and A.J. that even though two of their guests haven’t arrived, the wedding must start. He’s got a 4:30. He can’t wait anymore. Everyone hurries to their places while Chris makes a brief announcement to their guests. They’re allowed to take pictures, but everyone must remain in their seats until the end of the ceremony. I barely have time to wonder why this last instruction is necessary before— |

Catherine starts crying as soon as she enters the chapel. She cries her way to the altar, cries as she takes her place beside A.J., cries as the justice reads through the opening of the ceremony, cries more when the justice asks her if she’ll love her husband through sickness and through health. The bareness of her emotion infects everyone in the room.

I see three people in the front row hunch their shoulders and bring their hands to their

faces, then the man in the second row next to the wall, then the woman sitting next to him. It jumps the 12-year-old boy sitting next to her and moves to the third row, then the fourth. Now I am crying. We are all in the room crying. Everyone happy and flushed and sure that everything, everywhere is going to be OK after all.

And then, six minutes and 47 seconds after it begins, it’s finished. A.J. and Catherine are now husband and wife.

CHIP BROWN

“THE WAITING GAME,” 2005

Chip Brown has written two nonfiction books, as well as hundreds of articles for national magazines including

Esquire

,

Men’s Journal

,

Vogue

,

Harper’s

, and

National Geographic

. He contributed this essay to an anthology of men’s stories about love and commitment. Brown married fashion writer and editor Kate Betts in 1996.

I remember the sense of a larger force at work when my younger brother, Toby, got married at age twenty-five. Waiting for the ceremony to begin on the altar of an Episcopal church in Connecticut, he seemed relaxed, laughing when the young organist wove the theme from

The Flintstones

into the prelude. But when Anne appeared at the end of the aisle, he began to tremble. Maybe it was the rustle of the organ, but the sound in the church was like the clamor of surf, as if we were all standing by the ocean or inside a giant shell. You could feel the presence of the life force shuddering in its traces, impatient to get the ceremony out of the way so the real work of minting fresh DNA could begin. It seemed at that moment, free will notwithstanding, my brother and his wife were but the means to an end, the instruments of their genes, clapped together by a design much more consequential than their personalities, or their ostensible reasons for getting married. The machinery of life proceeds independently of vows.

WHEN

TRADITIONAL RHYME

If you’re wondering about weekdays . . .

Monday for wealth,

Tuesday for health,

Wednesday the best of all,

Thursday for crosses,

Friday for losses,

Saturday no luck at all.

TRADITIONAL RHYME

Or months . . .

Married in January’s hoar and rime,

Widowed you’ll be before your prime.

Married in February’s sleety weather,

Life you’ll tread in tune together.

Married when March winds shrill and roar,

Your home will lie on a foreign shore.

Married ’neath April’s changeful skies,

A chequered path before you lies.

Married when bees o’er May blooms flit,

Strangers around your board will sit.

Married in month of roses—June—

Life will be one long honeymoon.

Married in July, with flowers ablaze,

Bitter-sweet memories in after days.

Married in August’s heat and drowse,

Lover and friend in your chosen spouse.

Married in golden September’s glow,

Smooth and serene your life will flow.

Married when leaves in October thin,

Toil and hardship for you begin.

Married in veils of November mist,

Dame Fortune your wedding ring has kissed.

Married in days of December’s cheer,

Love’s star burns brighter from year to year.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

POOR RICHARD’S ALMANACK

, 1734

Franklin (see also

Rings

;

Why

) proposed to his wife, Deborah Read, when he was just seventeen and she was fifteen. Her mother refused the offer, partly because he was about to leave for England and partly because he had already fathered a child with another woman. Deborah married in Franklin’s absence, but her husband robbed and left her. Her ensuing common-law marriage with Franklin took place in 1730, when he was twenty-four, and lasted until her death in 1774.

Wedlock, as old men note, hath likened been,

Unto a public crowd or common rout;

Where those that are without would fain get in, And those that are within, would fain get out.

Grief often treads upon the heels of pleasure, Marry’d in haste, we oft repent at leisure;

Some by experience find these words missplaced, Marry’d at leisure, they repent in haste.

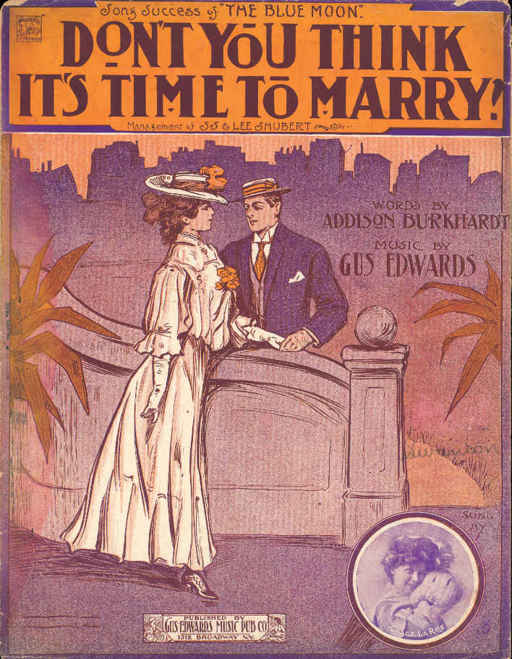

SHEET MUSIC COVER, 1906